WASHINGTON – Arizonans hoping for a break this spring from the drought gripping the state will be disappointed, with climatologists calling for minor to exceptional drought conditions, what one calls the state’s “new normal.”

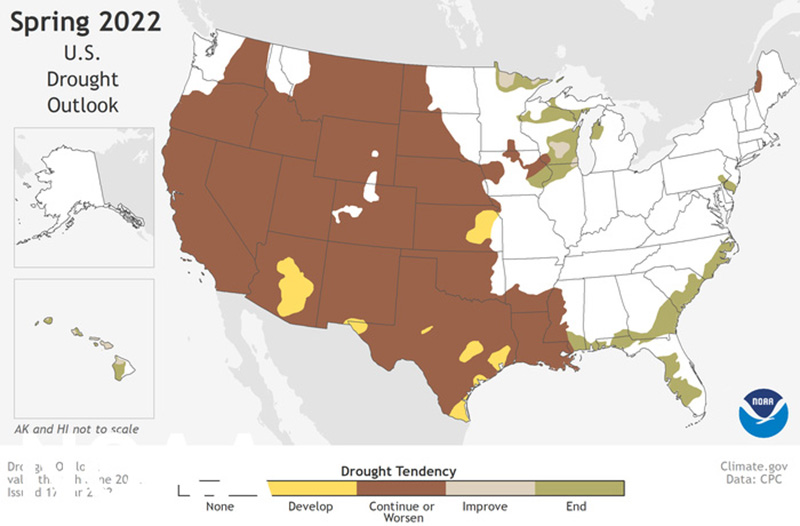

The spring outlook released this month by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted the largest drought coverage seen in the U.S. since 2013, with as much as 60% of the continental U.S. facing drought conditions.

“This outlook that NOAA is saying, that we’re going to develop or have worsening drought, it’s not surprising, it’s not unexpected,” said Erinanne Saffel, Arizona’s state climatologist.

As the state moves into April, May and June, what Saffel calls “the driest months of the year in Arizona,” dry conditions will impact roughly 4 million residents living in drought-stricken areas across the state, according to NOAA.

It said cities in central Arizona, including Phoenix, Tucson, Globe and Florence, will experience abnormally dry conditions characterized by dry soil and increased fire risks. The greater threat will be in western and northern Arizona, where severe or extreme drought conditions are expected to affect farms, forests and wildlife, and stress fire crews.

Despite last year’s monsoon season being one of the wettest on record, averaging 7.93 inches of rainfall, it was not enough to reverse lasting effects from prior dry seasons in Arizona – including the driest monsoon on record in 2020.

“We’re still in that long-term kind of situation where one or two wet seasons is still not enough to come out of this long-term drought,” Saffel said.

Like much of the country, Arizona faces a better than 50% chance that drought conditions will develop (yellow) or worsen (brown) between now and the end of June. (Map courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)

Arizona has been experiencing drought conditions since the mid ’90s and has been under an emergency drought declaration since 1999. Experts said that it’s important to look beyond short-term climate forecasts when considering the long-term drought.

“We’ve been getting precipitation that isn’t too far off from normal or 100% of average, but the runoff has been significantly less … indicative of very dry soil conditions and also a hotter, drier spring,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources.

NOAA’s spring forecast came shortly after the Bureau of Reclamation said the elevation of Lake Powell had fallen below 3,525 feet, the lowest since it was first filled in the ’60s. If the lake falls below 3,490 feet, it will not be able to turn generators in Glen Canyon Dam that produce electricity for 5.8 million customers in Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Nebraska and Arizona.

As part of the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan, the Bureau of Reclamation twice took actions to help prop up Lake Powell, releasing water from two upstream reservoirs and temporarily reducing monthly releases from Glen Canyon Dam until April.

The bureau said it would not be taking further action for now “because the spring runoff will resolve the deficit in the short term,” said Wayne Pullan, the director of the Upper Colorado Basin Region, in a prepared statement.

But Buschatzke does not share that optimism.

“We’ve been monitoring the climatic conditions for many years in relation to both what’s occurring inside the state of Arizona, but also with the major reservoirs Lake Powell, Lake Mead, and what was happening in the upper basin watershed for” those lakes, he said. “And it has been a downward trend in terms of runoff in the Colorado River.”

While it does not plan more action now, Reclamation projects that Lake Powell will dip again later this year, and it has a Drought Response Operations Plan in the works to help keep water at a level to keep Glen Canyon Dam generators functioning, if necessary.

Although the bureau has been able to provide short-term solutions, Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University’s Morrison Institute, argues that significantly more must be done to combat the shortages caused by “22 years of drought.”

“We’ve been doing these incremental agreements to deal with urgent situations,” Porter said. “But we need to get to a point where we have a big long-term agreement on how much water we can expect, and how much water each and every user can expect.”

These agreements will require cooperation between all of the basin states, and several iterations of plans and projections in order to achieve a “reasonable level of success,” Buschatzke said.

“Mother Nature keeps teaching us that things can get worse as you look forward,” he said. “So we need to continue to add to our plans and create more robust plans to deal with the broader range that is before us and the broader range of uncertainty about what our future will hold.”