PHOENIX – With childhood obesity levels on the rise in the U.S., more experts are looking at how to prevent high cholesterol in youth to help avoid serious health problems later in life.

Obesity increases the risk of developing high cholesterol, which can lead to heart disease and stroke, two of the nation’s leading causes of death.

One way to prevent unhealthy levels of cholesterol in adults is by preventing it in childhood, said Dr. Michael Domanski, a cardiology specialist and professor of medicine at the University of Maryland.

“High cholesterol early on stays with you,” he said. “It’s a true epidemic.”

Cholesterol is a waxy substance in the body. It helps build healthy cells, but when people have too much cholesterol, hard deposits can form in the arteries and restrict blood flow or cause clots – leading to heart attack or stroke.

For some, high cholesterol is genetic. For others, it stems from a diet high in saturated fat and animal products, as well as lack of regular exercise. Obesity also increases levels of so-called bad cholesterol, or LDL, while lowering good cholesterol, or HDL.

With gyms and schools closed for months on end, the pandemic put a dent in the physical activity of both children and adults, leading to weight gain.

The body mass index of youth 2 to 19 years old doubled in 2020 compared with pre-pandemic levels, according to a study published in September by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Another report, released by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in October, found that among youth 10 to 17, Kentucky had the highest obesity rate in the nation at 24%. Arizona’s rate was 10%, which is below the national average of 16%.

Overall, obesity is most prevalent in youth of color, data shows, with the highest rates in Hispanic and Black children.

As a group, Hispanics are “more prone to become overweight, obese or have excess body fat,” said Dr. Regis Fernandes, a cardiologist with the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix. “It kind of boils down to physical activity, sitting time and excess caloric intake.”

According to a report by the American Heart Association, 7% of children 6 to 19 have high cholesterol, which in younger people is considered 200 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dl) or above. Twenty-one percent are at borderline levels, 170 to 199 mg/dl.

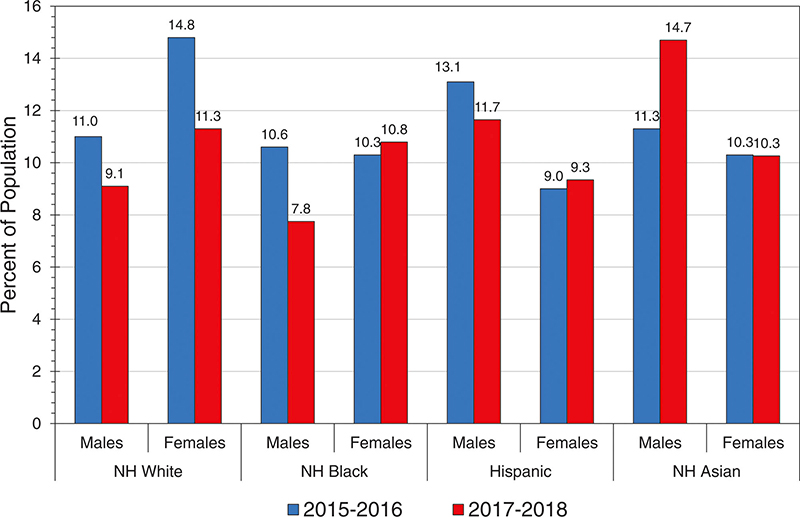

Nationally, 38% of adults have borderline high cholesterol, readings of 200 to 239 mg/dl, while about 12% have total cholesterol readings of 240 mg/dl or above. White women and Asian and Hispanic men have the highest prevalence in both categories.

This chart shows the prevalence of high cholesterol, 240 mg/dl or higher, in adults 20 or older by gender, race and ethnicity. (Source: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey)

Dr. Reshmaal Gomes, a cardiologist with Phoenix Heart cardiology group and board member with the American Heart Association’s Phoenix division, said more focus should be placed on diagnosing and treating high cholesterol before age 20.

“Over the years, we’ve focused more on the adults, but over the last several years what we found is that it doesn’t suddenly happen that you have high cholesterol when you’re an adult,” Gomes said. “It’s what has led to this point, and what can we do to find out and … change it.”

Because there are no signs or symptoms of high cholesterol, experts recommend that parents take their children for testing early on and work to increase physical activity and reduce screen time.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children ages 9 to 11 get screened for cholesterol levels. For those with certain risk factors – parents or grandparents with cholesterol levels at 240 or higher, or who have had heart attacks – a first cholesterol test should be given at 2 to 9 years of age.

Teachers prepare the community garden at Garfield Elementary School’s Garden on the Corner. (Photo by Hope O’Brien/Cronkite News)

Terri Drain, president of the Society of Health and Physical Educators, or SHAPE America, said it’s important to educate youth about why physical activity matters and how they can become more active.

“Physical literacy is the confidence and motivation to move,” said Drain, whose organization develops standards for physical education training in schools. “When kids are physically literate, they are more likely to engage in physical activity.”

If a child learns how to throw, for example, he or she will be more likely to engage in games that involve throwing, such as softball, baseball, frisbee or catch, she said.

But physical literacy is also about changing childrens’ attitudes toward regular activity and helping them understand how that can enrich their lives.

“It’s about the love for movement,” Drain said.

Educating children and their parents about eating healthfully is another way to control obesity and cholesterol, experts say.

Near downtown Phoenix, Garfield Elementary School’s Garden on the Corner gives children the chance to grow their own vegetables and eat them in their school lunches, all while learning about the importance of healthful eating.

“It’s a way of instilling the habit young, rather than more modification and having to work on those habits later,” said Paige Mollen, president of the Mollen Foundation, an Arizona nonprofit founded in 2008 with a mission of combating childhood obesity.

“They actually get to see it in the school cafeteria, on the menu, which is really exciting,” Mollen said. “And it also promotes local food, healthy soil, and that just creates more nourishment for the students.”

Cronkite News reporter Molly Hudson contributed to this story.