WASHINGTON – The COVID-19 pandemic and a growing unsafe drug supply combined to push overdose deaths up by 27.6% in the U.S. over a 12-month period from 2020 to 2021, a surge in deaths that was matched in Arizona.

Nationwide, the estimated 98,331 drug overdose deaths reported from April to April set a record, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which said the national overdose death toll for the preceding 12 months was 77,011.

The increase in Arizona almost exactly matched the U.S. rate, rising from 2,146 overdose deaths between April 2019 and April 2020 to 2,743 deaths the following year, a 27.8% increase, according to the data.

While the revised numbers for April did not top 100,000, as was first expected, they still set a record for overdose deaths in the U.S. Experts blamed a perfect storm of events for the rise, beginning with the onset of COVID-19 in early 2020.

“With the pandemic, people are forced to use in ways that are more risky,” said Haley Coles, executive director at Sonoran Prevention Works. “It has also really changed the drug market.

“When we see people’s social and economic lives become more stressful, we see people start to use more or in riskier ways,” Coles said. “And – now that we’ve encouraged people to isolate – when you’re by yourself and you’re using, there’s nobody there to help you if you overdose.”

But the pandemic was not the only circumstance behind increase in overdose deaths.

Dr. Raminta Daniulaityte, associate professor at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions, said the state has seen an increase in the availability of counterfeit pills, also known as “blues” and “dirty oxys.”

A Drug Enforcement Administration fact sheet said such counterfeits may appear to be legitimate prescription pills, like oxycodone, but may actually contain other ingredients or have lethal levels of drugs like fentanyl or methamphetamine.

“There is a market for these drugs,” Daniulaityte said. “And many people who were long-term users or were exposed to prescriptions of pharmaceutical opioids – because of the regulations that were implemented – were just cut off from the sources and had no significant intervention to help them deal with their dependence and were forced to turn to illicit opioids.”

The regulations she was referring to were in the 2018 Arizona Opioid Epidemic Act, which limited health professionals to prescribing initial opioid prescriptions with no more than five days of pills. It also prohibited them from prescribing opioids that exceed 90 morphine milligram equivalents per day.

Will Humble, executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association, said state officials “dusted their hands off” after the passage of that act and moved on from the ongoing problem of opioid overdoses.

“In the years since the act, the number of fentanyl deaths has really skyrocketed and deaths from prescribed drugs have flattened out,” Humble said. “As Arizona cracked down on prescribed opioids, we didn’t improve the network that was available for people to get treatment for their opioid use disorders.”

But Sheila Sjolander, assistant director of the Arizona Department of Health Services, defended the state’s ongoing response, saying the department has implemented strategies to help combat the opioid epidemic.

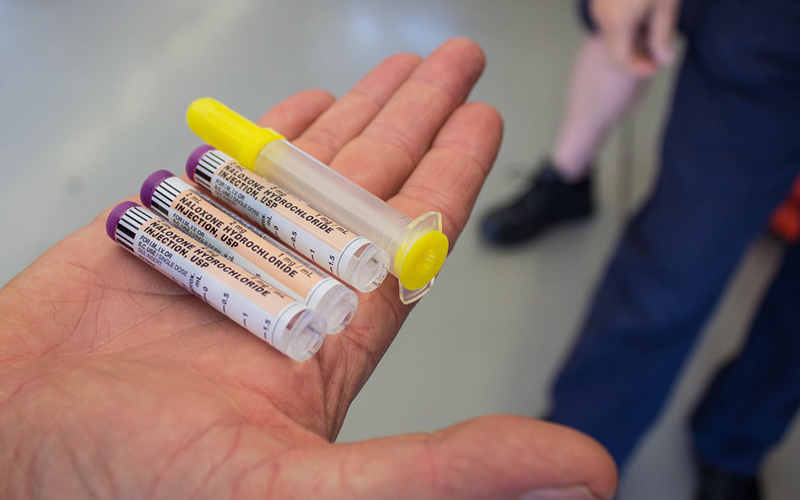

“One of the strategies, in terms of saving lives, is getting naloxone out in the community,” Sjolander said.

Naloxone is a medication that quickly reverses an overdose by blocking the effects of an opioid, according to the CDC. The life-saving medication can be used as either a nasal spray or an auto-injector.

First responders, Sjolander said, have implemented “leave-behind programs,” where they will leave doses of naloxone with individuals who have overdosed but did not go to the hospital.

Coles said her organization has distributed more than a half-million doses of naloxone and has had 17,000 overdose reversals reported to them as a result.

“We’ve been distributing naloxone – the overdose reversal medication – for about five years now,” she said. “And continuing to distribute that naloxone primarily to people who use drugs is really crucial.”

But Coles said there’s more to be done.

“There’s, unfortunately, so much stigma and discrimination and bad information about drugs, so people are then not able to take certain precautions,” she said. “And so much of that is based on the fact that drug use is criminalized.”

Coles said that incarcerating people for drug use is “not only not working, but it’s perpetuating the crisis” because people lose their tolerance when in jail but use the same dosage of drugs when they get out – something that is also accounting for overdoses in the state.

“Our approach to dealing with drug use is just not effective,” Coles said. “We need continued support to fund programs that will allow us to reach people who are at the highest risk of overdose.”