CHANDLER – In a small classroom with brick walls and dimmed lights, six students at BASIS Chandler sit quietly as they watch a presentation about mental health.

“What could happen if someone with a mental health issue doesn’t get treatment?” asks Katy-Marie Becker, a behavioral health nurse educator for Banner Health.

A student raises her hand. “Um, it’s probably going to get worse.”

Teens are struggling more than usual with their mental health, due to social isolation, economic instability and other worries surrounding COVID-19. Across Arizona, schools are trying to help students protect their emotional well-being.

BASIS Chandler, with students in grades 5 through 12, uses a program called Ending the Silence, developed by the National Alliance on Mental Illness. It identifies the warning signs of mental health conditions and the proper steps to take if the student or a loved one are exhibiting those signs.

Ananya Ravichandran, a senior at BASIS Chandler, is president of the on-campus Bring Change to Mind club, where mental health is openly discussed. The national nonprofit was co-founded by actress Glenn Close after her sister was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and her nephew with schizoaffective disorder.

Ravichandran said the daily pressures of school are just one cause of anxiety and other mental health problems among children and teens. In U.S. News & World Report’s top high school rankings, BASIS Chandler is ranked first in the state and eighth nationally. Its Advanced Placement coursework participation rate is 100%, and 77% of students are Asian.

“This school is a very academically challenging school,” she said. “I think a lot of students recognize that there needs to be more in terms of mental health support. So that’s what made me want to join this club and be more involved in it.”

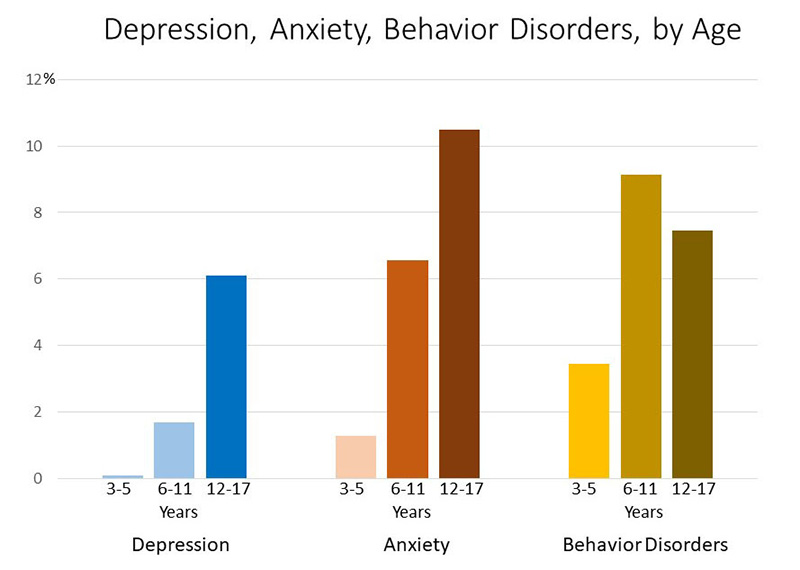

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, rates of mental disorders change with age. For example, diagnoses of depression and anxiety are more common as children get older. (Graphic courtesy of CDC)

Depression and anxiety among ages 6 to 17 have been on the rise, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 9% of children younger than 18 have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, 7% with anxiety and 3% with depression.

These conditions affect some children more than others. One CDC study found that about half of LGBTQ high school students and about one-third of those unsure of their sexual identity had seriously considered suicide, compared with 15% of heterosexual students.

And among children living below the federal poverty level, 22% – more than 1 in 5 – have a mental, behavioral or developmental disorder, according to the CDC.

In March 2020, just before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, Gov. Doug Ducey signed SB 1523, also known as Jake’s Law, requiring health care insurers to cover mental health without extra obstacles and allocating $8 million for behavioral health services for children who are uninsured or underinsured.

Jake’s Law will get more mental health support to those in need. This historic reform is the product of months of work. Thank you to @KateMcGeeAZ, @JeffWeninger, @FannKfann, Speaker Bowers & everyone who worked to make this unanimous achievement possible. @FoundationJEM pic.twitter.com/9gdSiQ2uds

— Doug Ducey (@DougDucey) March 3, 2020

The legislation was named for Jake Machovsky, who at 15 lost his life to suicide after battling mental health issues. In a blog post for The Kennedy Forum, Jake’s mother, Denise Denslow, said her son had been hospitalized twice in five weeks for suicidal ideation. Both times, he was released after five days.

“We knew, deep down, if Jake had a life-threatening physical condition, he never would have been released from inpatient care,” she wrote. “Tragically, less than three months later, he was gone.”

The pandemic exacerbated all of these problems. Several studies have found that psychological conditions among youth worsened during COVID-19, and that those with preexisting conditions were at higher risk.

A study by the national nonprofit FAIR Health found that mental health claims for 13- to 18-year-olds in March and April 2020 roughly doubled compared with the same months the year before. Intentional self-harm claims in the same age group increased by 90% from March 2019 to March 2020.

Aedan Hanley, a student prevention intervention specialist at Central High School in Phoenix, has observed more apathetic behavior from students since in-person learning resumed this fall.

“There’s this sense that this isn’t going to last; we’re going back to virtual learning. So how much investment do I want to put here?” he said.

Central is part of Phoenix Union High School District, a large urban district in which 81% of students are Latino, many are refugees, and more than half speak a primary language other than English at home.

The school sent a needs assessment to its 1,800 pupils at the beginning of the 2021-22 school year, and more than a third of students responded. Forty percent self-reported unmet social, emotional or mental health needs and dramatic changes in behavior, while 30% responded that they were struggling with peer relationships and gender or sexual identity.

Hanley is one of five behavioral health staff at Central High, which is partnering with Southwest Behavioral Health to provide more support for students’ mental health needs.

In April, Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Kathy Hoffman announced $21 million in funding for more counselors and social workers in public schools. The state has the highest student-to-counselor ratio in the nation at 848-to-1. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250-to-1.

Tempe Union High School District implemented a student mental health and social/emotional wellness program at the start of this school year. The district serves a diverse population, including students from the town of Guadalupe, the Gila River Indian Community and parts of Chandler.

During the first week of school, a half-hour was set aside at the beginning of each class for students to connect with their teachers and one another, after being off-campus for much of the previous year, district board member Armando Montero said.

“We recognize that it’s a very tough time to be a student right now. And we’re making sure that we’re doing whatever we can to connect you with the right resources,” Montero, who graduated from the district in 2018, said in an interview.

The program includes encouraging conversations about mental health to reduce stigma and matching students with adult leaders who’ve had similar experiences. A social and emotional wellness coordinator at each of the six high schools in Tempe Union will focus on student interventions, including suicide prevention. The plan also includes “postvention,” where a crisis team responds following a death by suicide.

“I went through a lot of my own challenges in high school and lost a friend of mine my sophomore year,” Montero said. “So that kind of catalyzed me to get involved in the local school board and to really help raise the alarm of the mental health crisis that our youth are facing right now.”

As part of her presentation at BASIS Chandler, Becker shares her own mental health story. She had a hard time sleeping in high school but ignored the issue, even though her parents are recovering addicts with mood disorders.

“I am painfully good at functioning on two hours of sleep, which is not good for you. But I learned to do it,” she said.

Fast forward to 2015 when Becker, then 24, was stressed at work and once again unable to sleep. She remembers snapping at her husband and having nightmares about going to her job as a behavioral health nurse. Becker tried to rationalize her feelings by telling herself she didn’t have it as bad as the patients she treated.

“Part of me felt like maybe I didn’t deserve to go get better,” she said, adding that she ignored the signs until she no longer could.

“I remember driving in my car and I had some really scary, intrusive thoughts. ‘You should just crash your car into that wall.’ I was like, ‘I should not do that,’” she recalled.

After seeking help, she was diagnosed with cyclothymia, a disorder characterized by significant swings in mood and energy levels. Becker is now in recovery with the help of a therapist, psychiatrist, medication and her support group.

Becker finishes her presentation by encouraging the students to grab pamphlets and rubber bracelets in lime green, the national color of mental health awareness.

She advises the audience to tell their friends about Ending the Silence, mentioning a pediatric behavioral health unit that opened in August at Banner Thunderbird Medical Center in Glendale.

“With COVID,” she said, “we’ve seen a lot of kids come in – a lot of young kids, high school kids. So we want to get the information out there.”

The projector flickers as the students look on. They crowd around Becker to ask questions and grab the resources she brought with her. One of them is a card, with mental illness and suicide warning signs printed in tiny letters on one side, and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on the other.

The hotline is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or via online chat.