PHOENIX — Handle the moment.

That was the thought running through Lisa Byington’s mind as she prepared to call the NCAA Men’s Division I Basketball Tournament for Turner Sports last March.

And handle it, she did.

Byington made history as the first woman to call a March Madness game – an achievement that might have seemed improbable just a decade ago – and she handled the moment that No. 14-seed Abilene Christian celebrated a stunning victory over third-seeded Texas by doing something that few broadcasters are willing to do: she fell silent.

“I literally pushed myself away from the broadcast table,” Byington said. “We call it ‘laying out’ and that means literally not saying anything, because the pictures tell everything.”

Months later, Byington broke through another barrier when the Milwaukee Bucks named her the first full-time female television play-by-play voice for a men’s professional sports team.

Shortly after that, broadcaster Kate Scott was named lead play-by-play announcer for the Philadelphia 76ers.

The two busted through a glass ceiling women have butted up against for years while trying to advance in sports broadcasting. And nobody watched with more interest than Ann Meyers Drysdale, who has busted through a few glass ceilings herself.

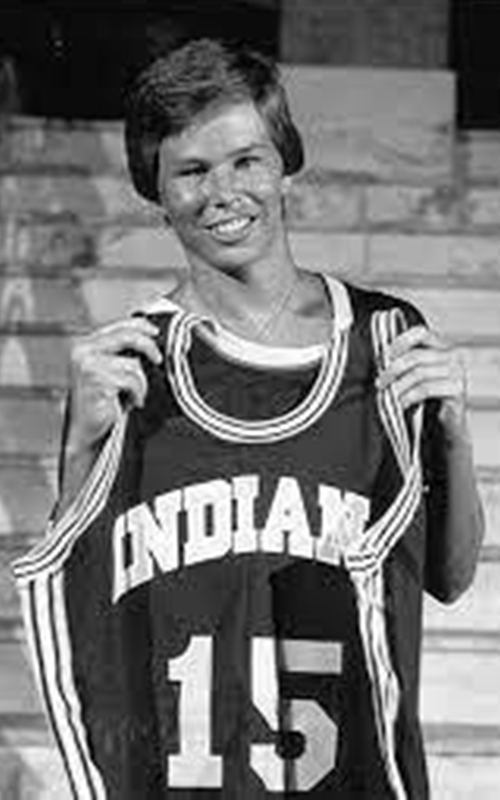

Meyers Drysdale was the first woman to sign a contract with a National Basketball Association team, the Indiana Pacers. (Photo courtesy of Indiana Pacers)

Meyers Drysdale was the first woman to ever earn an athletic scholarship to play basketball at UCLA in 1974, just two years after Title IX was ratified in 1972. The Indiana Pacers signed her to a $50,000 training camp contract in 1979 and gave her a tryout, another first.

And following her playing career, Meyers Drysdale became a trailblazer in the broadcasting booth, too.

She served as an analyst on men’s and women’s basketball broadcasts in the Olympics, WNBA, NBA, and NCAA for the likes of ESPN and NBC since the 1970s. Now, she serves as a vice president and broadcast analyst for the Phoenix Suns and Mercury.

Broadcasters such as Meyers Drysdale, Scott and Byington are used to the challenges that come with being a woman in a predominantly male industry.

For Byington, it was no different with the Bucks.

When she interviewed for the job, Byington made sure to turn one interview question back to the organization. They asked her how she would handle the moment of being the first woman to be the voice of an NBA team.

“I kind of put it back on them. And I said, ‘How are you guys gonna handle it? It’s new for you, for Milwaukee, for the NBA. It’s new for everybody else except for the person you’re asking how you’re going to handle it,’” Byington said.

Meyers Drysdale’s biography is full of accomplishments that paved the way for talented broadcasters like Byington. But Meyers Drysdale is quick to credit others who came before her as well as those that she has worked alongside.

“I worked with Robin Roberts, and Michele Tafoya,” Meyers Drysdale said. “I’ve worked with Pam Ward. Beth Mowins has done play-by-play in football just like Ward. We’ve got a lot of women that are doing play-by-play that are qualified.”

Meyers Drysdale was a broadcaster on the first WNBA game in 1997 alongside Hannah Storm. She also served on the first NBA game to feature two female analysts alongside Stephanie Ready.

She always handled the moment – especially the ones that shattered those glass ceilings.

Meyers Drysdale never planned on carving out a legacy in broadcasting, but longtime play-by-play voice and former SportsCenter anchor Cindy Brunson feels the impact Meyers Drysdale had on her every day.

She showed Brunson what was possible.

“She’s like Billie Jean King in that respect. She doesn’t want the road with her at the end of it,” Brunson said. “She wants it to keep going for everybody.”

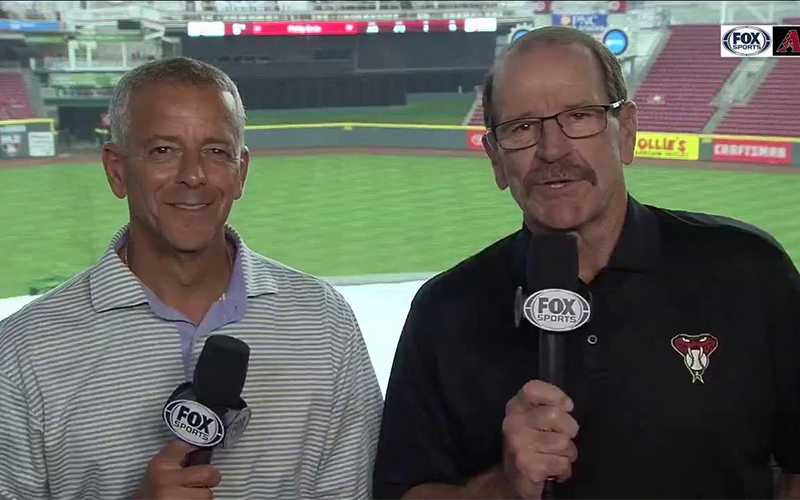

Cindy Brunson (left) interviewed with the Philadelphia 76ers and Sacramento Kings for their open play-by-play positions. (Photo courtesy of Bally Sports Arizona)

Brunson lives in Arizona with her husband Steve Berthiaume, who serves as the television play-play broadcast announcer for the Arizona Diamondbacks. Brunson works as a play-by-play announcer and sideline reporter for the Pac-12 Networks and WNBA covering women’s and men’s basketball, college football, and softball.

During the NBA offseason, she interviewed with the Philadelphia 76ers and Sacramento Kings for their open play-by-play positions.

Like Byington, Brunson turned one question back on the organization when she interviewed.

“Some of the folks at the Sixers and at the Kings were like, ‘Well, how do you think you’re going to handle this,’” Brunson said. “(I said) ‘I believe in what I’ve got going for me. How are you going to handle it? Because you’re going to get the blowback. I’ve been told all my life, I can’t. And I just keep pushing and succeeding.’”

Brunson did not receive an offer for the positions, but she opened the eyes of team executives to a far bigger conversation on female representation in a male-dominated industry – a conversation which makes many people wonder why it took until 2021 for women like Byington and Scott to get their break.

Brunson made it clear that, while she might not be one of the first women to break the barrier, she won’t be the last, either.

“When I interviewed with the Sixers, I said, ‘Look, it’s not just me in the car,’” Brunson said. “(I said) ‘Everybody in the backseat looks like me, and they’re younger than me. And I’m driving them down the road.’”

Byington has a simple goal for future generations in the play-by-play space.

“I would say I hope that one day a female voice on a men’s game becomes background noise,” Byington said.

At the moment, Byington and Scott are more than background noise because they are the first women in the play-by-play space for major men’s pro sports. But, Drysdale knows from experience that just getting there isn’t enough.

“We do not have to just be grateful that we’re at the table, we have to own the table, too,” Drysdale said. “We have to make sure that we are part of the conversation, and that our voice matters.”