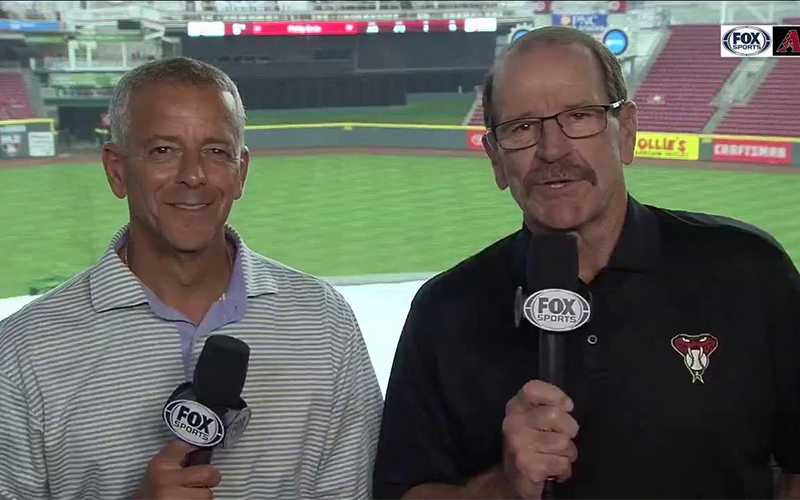

After news broke in 2020 that former Arizona Diamondbacks broadcaster Thom Brennaman (left) used a homophobic slur that was caught on a hot microphone during a commercial break, debate ensued about the proper punishment. (Photo courtesy of Bally Sports Arizona)

PHOENIX – The court of public opinion is nothing new, and plenty of sports broadcasters have recently faced it.

In August 2020, Thom Brennaman, then the play-by-play voice of the Cincinnati Reds for Fox Sports Ohio, used a homophobic slur to refer to an unspecified city as “one of the f– capitals of the world.” The remark was caught on a hot microphone during a commercial break of the Reds game against the Kansas City Royals, and quickly circulated around social media.

Brennaman, who spent eight years as the Arizona Diamondbacks play-by-play broadcaster, apologized on air before receiving a suspension from the Reds. Later, his contract was not renewed by Fox Sports.

Brennaman is far from the only broadcaster in sports to make a derogatory or discriminatory statement while the microphones are on. Earlier this year, Matt Rowan, a high school broadcaster in Oklahoma, used a racial slur after the Norman High School girls basketball team knelt during the national anthem.

Detroit Tigers announcer Jack Morris was placed on an indefinite suspension by Bally Sports Detroit in August after using a mock Asian accent while discussing Los Angeles Angels star Shohei Ohtani. And, in 2016, Fox Sports removed Emily Austen as the Orlando Magic and Tampa Bay Rays sideline reporter after she made racist and insensitive remarks on a Barstool Sports Facebook live stream.

In each case, the broadcaster gave — sometimes clumsily — an apology.

But is an apology enough?

In an era when terms like political correctness and cancel culture circulate frequently, at what point, if ever, is it appropriate for sports figures to resume their jobs?

It isn’t a cut-and-dry situation, experts say. There isn’t an agreed-upon punishment or length of time that needs to pass before deciding that the offender is remorseful and has learned from their transgression.

‘The steepest of punishments’

In September, a column appeared in the Sports Broadcast Journal that argued Brennaman deserves to work again because “he’s (suffered) the steepest of punishments, the loss of his coveted career” after using a homophobic slur.

“Unfortunately, announcers who misspoke are thrown into an imaginary dungeon! They’re forced to crawl in darkness 24/7 with no light to end the misery,” David Halberstam wrote. “Verbal transgressions, yes, they can be nasty. Still, decision makers should mull whether the wrongdoer is capable of reform or is he or she incorrigible? America is a country of second chances. Allow voices to get back into their broadcast lanes.”

Some would argue that the use of “misspoke” by Halberstam is an inaccurate description of Brennaman’s actions. Lisa Kihl, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota and director of the Global Institute for Responsible Sport Organizations, said the focus should be on how easily Brennaman used the slur.

“He just thought he could say it and get away with it. For it to slip off his tongue, it means he’s probably said it before,” she said. “It’s used in his common language.”

Often, people who are heard using insensitive language are quick to defend themselves.

“Something that we see quite often is that people who use homophobic language, specifically in sports, will often say that they don’t think of themselves as being homophobic, or they don’t even think of the word as being homophobic,” said Joanna Hoffman, the director of communications for Athlete Ally. “They say, ‘Oh it’s just like a word I say.’ But it doesn’t matter what their intent is because the impact is still the same.

“The impact is still that because sport culture has that kind of language baked into it.”

Athlete Ally, an organization that strives to bring equal access to sport, regardless of gender identity, sexual orientation or gender expression, argues that the LGBTQI+ community remains systematically excluded from sport.

Hoffman said Brennaman, and others, using homophobic language on a broadcast sends a message to LGBTQI+ athletes and fans that “sport is not a safe place for them.”

Halberstam, the columnist, who spoke with Brennaman for his column, wrote that Brennaman has “spent most of the past fourteen months befriending the gay community” and has “gotten to know a gay minister of an Episcopal Church and a gay top executive at Johnson & Johnson,” in addition to his on air apology.

But, again, is an apology enough? Is spending a few months talking to the gay community enough?

That depends on whom you ask.

‘How it’s framed’

“I think an apology is the right step, but I think how it’s framed is important,” Hoffman said. “I think the wrong way to apologize is to say something like, ‘I’m sorry if people were offended or I’m sorry people took it that way,’ as opposed to saying like, ‘I recognize that this kind of language perpetuates an unsafe environment and I’m sorry I contributed to that.’”

“It’s not for him to do a full 180 and say, ‘I’ve really reflected on myself as an individual,’” Kihl said. “If you’re really sincerely sorry, then you’ll do certain things, and I just don’t think volunteering is enough, and saying you’re sorry is enough.”

For Doug Glanville, a former MLB outfielder and current baseball broadcast analyst, words carry weight. As a Black broadcaster, Glanville experiences situations differently. Words don’t just slip out. They aren’t accidents.

Glanville offered these thoughts in a story he wrote for ESPN after Jim Kaat made a reference to promised slave reparations during Reconstruction while discussing Yoan Moncada during Game 2 of the ALDS:

“It is also important to understand that our words do not land in a vacuum. On air, the millions of viewers paying attention to our every word make nuance and context difficult. That may be an extra burden to broadcasters, but it does not make it less true. It also means that we have a responsibility to understand the true impact of our words — and realize that used loosely, they may devastate not just the millions of diverse fans impacted by what we say as commentators in every game, but also a person in your industry who is 1,000 miles from the game you are calling, who can see himself in the booth right next to you. Words matter. But understanding matters more.”

So when is an acceptable time to allow broadcasters to resume their job after using insensitive language?

“I think that it is a case by case situation, because I do think that people can evolve and grow. There’s just a lot in (the column) that just indicates to me that (Brennaman) feels like he’s the victim in all of this, which is concerning,” Hoffman said. “That shows, to me, that he is not really reflecting on it in the way that we would hope, but that doesn’t mean he’s not going to get his job back. Ultimately, it’s up to the people in power who may not be thinking about LGBTQI+ inclusion in the same way, unfortunately.

“In an ideal world, we would see there being specific kinds of education or training that he would commit to in order to get his job back, but it’s hard to say. It’s hard to make something like that uniform.”

In the case of Jack Morris, the Tigers announcer, Bally Sports Detroit said he will have to undergo bias training to understand the impact of his comments. However, in most cases, there aren’t procedures that television stations are required to follow.

Organizations remove the announcers quickly following the use of insensitive language. This isn’t a lifetime ban on broadcasting.

In fact, there are examples of broadcasters’ rejoining the field in different roles.

Brennaman joined the Roberto Clemente winter league in Puerto Rico to call games in December 2020, just months after receiving a suspension from the Reds. Austen joined Liberty University’s sports show as an anchor and reporter in 2019, about three years after losing her job with Fox Sports.

Cancel culture insinuates that people are never allowed to resume their careers. Or, in Kihl’s view, cancel culture is “white people deflecting.”

“Instead of saying, ‘Let’s look at what this man said, and let’s look at the impact on the people that he said it about,’ (they) call that cancel culture and dismiss (the impact of the words). ‘Oh it’s some sort of nutty behavior.’ No, this is really unethical behavior and an organization should not have people like that representing them,” she said. “Because if they don’t hold them accountable, then it says that the organization condones the behavior in my perspective.”