With Arizona’s healthy monsoon and an explosion of mosquito-borne West Nile virus cases, Yuma County has partnered with the Cocopah Indian Tribe south of Yuma to create an effective shield against the disease.

For the first time, Yuma County’s Pest Abatement District provided training and supplies to the reservation for mosquito surveillance and mitigation. That allowed the tribe the flexibility to react to rising cases in real time and use a variety of methods to prevent infections.

Their timing turned out to be fortunate. So far, the county has had zero cases in a year when parts of the state are seeing record infections, thanks to ample summer storms. Maricopa County alone has reported 182 cases as of mid-October, compared with just a few last year. Deaths statewide so far have reached 24, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services.

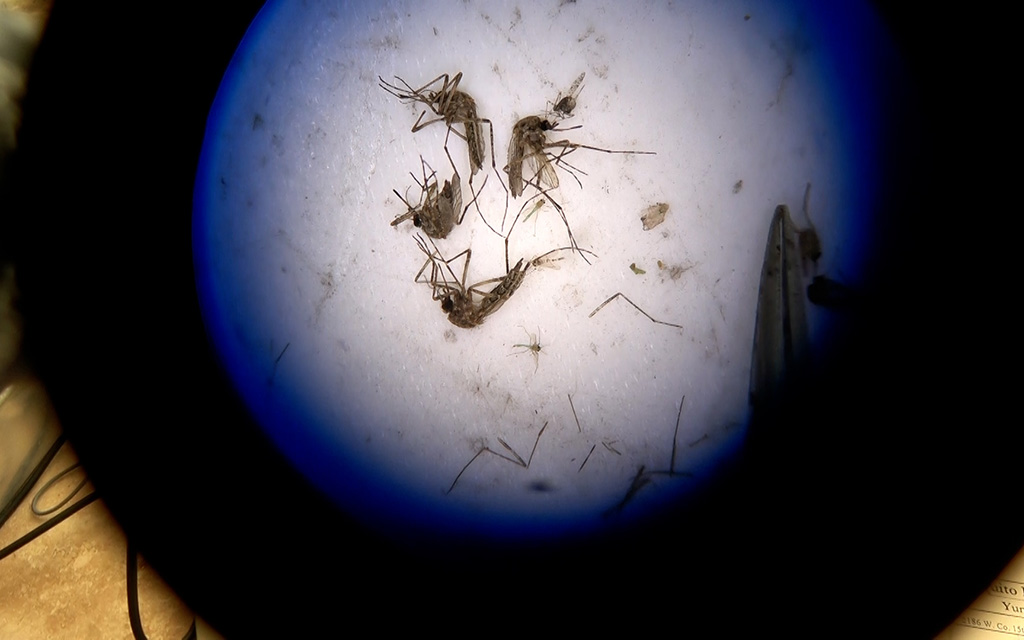

“We test every two weeks. Take mosquito samples throughout the county and populated areas along the river, and we test those,” said Richard Cuming, environmental vector control specialist at Yuma County. “Here, we try to keep the mosquitos out of the populated areas and in those rural areas where a lot of people really don’t go.”

The county’s East and West Wetlands areas are heavily populated and known to be mosquito hotspots because they’re close to the Colorado River.

Before, the Cocopah’s Environmental Protection Office outsourced mosquito surveillance and abatement to the federal Indian Health Services. Now, the partnership with Yuma County allows the tribe to perform its own tracking and surveillance of mosquitos infected with the West Nile virus or other types of encephalitis.

Vector specialists normally use dry ice traps to collect and test mosquitoes for West Nile. But supplying dry ice to county agencies has been difficult, which limits testing.

Yuma has also been resourceful as the only county in the state to also use chickens to test for West Nile. Poultry is known to create antibodies against the virus, and chickens are used as sentinels. There are five chicken flocks throughout the county that are tested twice a week.

“The reason why we have that program is because we can’t have dry ice every week to test,” said Elene MacAdam, the county’s Pest Abatement District manager. “Other communities like Phoenix and Tucson test two or three times a week. We don’t have that resource available to us, so we have to look at other types of surveillance.”

The Cocopah Indian Tribe also runs a campaign called Fight the Bite to promote public health and awareness around West Nile. The Tribe gives residents free mosquito repellent and distributes videos encouraging residents to clean up standing water and wear DEET when outside.

“We really appreciate people tuning into our videos and sharing them,” said Jen Alspach, director of the Cocopah Environmental Protection Office. “Just getting the message out to people. I think that’s really where it starts, in your family.”

The Cocopah this year launched a live stream from the Yuma County Pest Abatement District Office, where tribal members could post any questions about the virus or report any high mosquito activities.

The risk of being bitten by an infected mosquito has dropped since the beginning of the season from six to 10 infected mosquitoes per test to none. In the past few years since Yuma County has created partnerships like the one with the Cocopah, they have seen a huge reduction of mosquito breeding hotspots throughout the county.

“If everybody is doing a really good effort across the board,” MacAdam said, “then we’re not having these hotspots flaring up and flaring up untreated.”

But even with the robust abatement system, the success can’t be attributed entirely to the mitigation efforts. Some of it is just the nature of the disease.

The agency says in some years, they can do the same amount of mitigation as the previous and have different amounts of mosquitoes test positive for West Nile virus. There’s no explanation for it.

“It has a mind of its own,” MacAdam said.

For the county and the tribe, success is a combination of factors. Surveillance, fogging, adulticides and larvicides in part, but also community vigilance and involvement and luck.

“As we say in mosquito control, it’s kind of like a box of chocolates,” MacAdam said.