New research shows a surge in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in youth, and some of the biggest increases are in Black and Hispanic children. A project at Arizona State University incorporates exercise and nutrition programs to help combat the disease in Hispanic youth. (Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News)

PHOENIX – When Nahomi Garcia was young, she usually had some sort of sweet treat or snack around the house. Her mother often cooked, but she still enjoyed Flamin’ Hot Cheetos or the sweetbread her grandmother loved.

But at the same time, Garcia began to worry about both her weight and her health – especially the potential for developing diabetes, which affects Hispanics in the U.S. at disproportionate rates.

At 14, Garcia and her mother took action. The teen was enrolled in a 12-week intervention program and study conducted by researchers at Arizona State University aimed at helping Hispanic youth combat diabetes.

“I had never worked out in my life up to that point,” said Garcia, who’s now 24. “But there was always somebody there to either push you a little bit more or tell you that you’re doing good.”

Her experience with food habits and health is one shared by an increasing number of adolescents across the country.

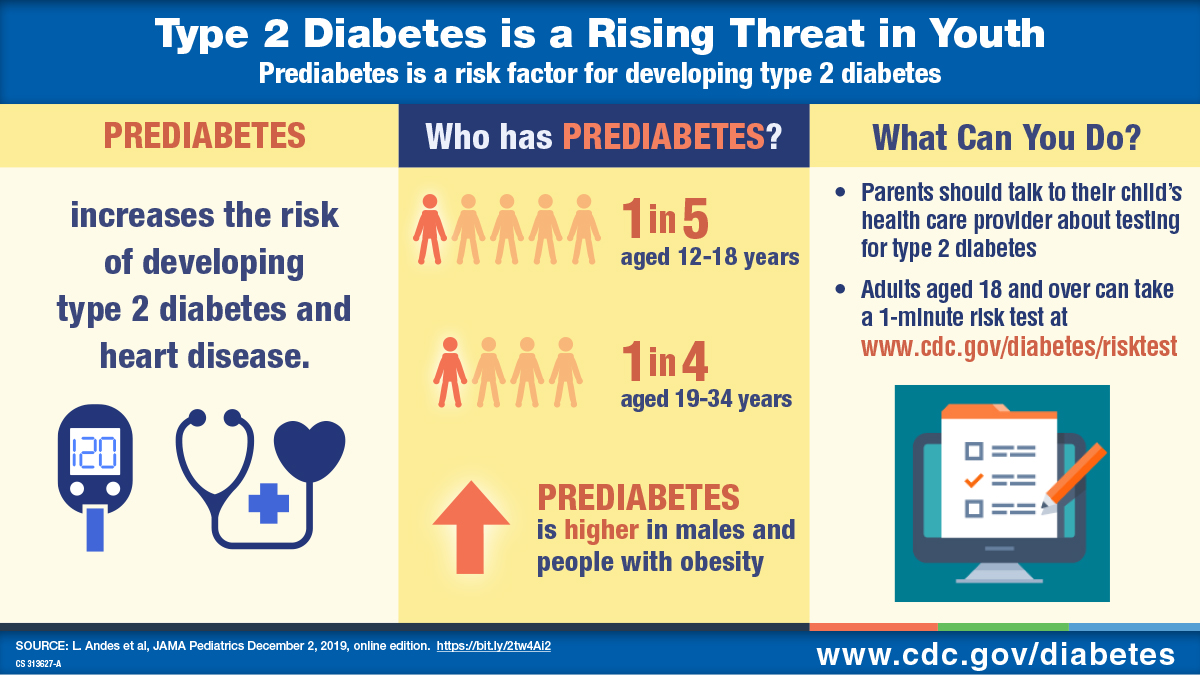

A study published in August in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA, shows the prevalence of both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in children and youth has surged. From 2001 to 2017, the number of people younger than 20 with Type 1 diabetes rose by 45%, while those with Type 2 diabetes soared by 95%. For Type 1, the biggest increases were in Black and white youth, while Black and Hispanic youth had the biggest increases in Type 2 cases.

Type 1 diabetes, which usually develops in childhood or adolescence, occurs when the pancreas produces little or no insulin to help the body regulate blood sugar. It is less common than Type 2 diabetes, in which patients produce insulin but their bodies don’t use it properly.

More than 34 million Americans have diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and 90% to 95% have Type 2, which often can be managed with healthy eating and exercise.

Jean Lawrence, lead author of the JAMA study and director of the diabetes epidemiology program at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, pointed to an increase in childhood obesity, particularly in Black and Latino teens, as one reason for the increasing diabetes rates.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth is associated with obesity and exposure to maternal diabetes and obesity during pregnancy, family history of diabetes, and genetics,” she said in an email to Cronkite News. “Therefore, healthy lifestyle and achieving and maintaining a healthy weight is important for everyone.”

Lawrence added, however, that a one-size-fits-all approach to diabetes prevention won’t work.

“This study highlights the diversity of the population impacted by diabetes. … Interventions that are tailored to these diverse groups may be more likely to be accepted, adopted and sustainable than a single approach to prevention and treatment,” she said.

That’s where programs like the one Garcia attended can help.

From 2012 through 2015, about 80 youth ages 14 to 16 participated in a structured, three-month exercise and nutrition program.

The teens would exercise three times a week, for 60 minutes a session, at a local YMCA, participating in activities like running, spinning and team sports. With their parents, they also attended weekly nutrition classes, conducted in both English and Spanish by health educators and registered dietitians from St. Vincent De Paul. Homework assignments included shopping for different types of vegetables and preparing them at home.

Gabriel Shaibi, a professor at ASU’s College of Nursing and Health Innovation, has for years been leading research into how to prevent diabetes in Hispanic children and teens. Shaibi is continuing his work with a four-month, family-focused diabetes prevention intervention, funded by a new $3.3 million federal grant. (Photo courtesy of Arizona State University)

After the initial three-month program, the teens returned for monthly “booster sessions” for another three months to reinforce healthy behavior changes and address any challenges.

Researchers with ASU’s Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center found that participants in the intervention program saw reductions in body mass index and body fat, and improvements in their overall health.

“So what we saw is that these kids got better,” said Gabriel Shaibi, the principal investigator and a professor at ASU’s College of Nursing and Health Innovation. “So it worked. And then the question is: How sustainable is the work?”

Shaibi said researchers are bringing back some past participants to see how they’ve transitioned to adulthood and evaluate how effective the initial interventions were and what external factors might influence their health over time.

The research was intentionally designed with cultural values in mind, particularly that of the family bond, and focused on encouraging the entire family to make healthy lifestyle changes.

Shaibi will continue his work with a four-month, family-focused diabetes prevention intervention, funded by a $3.3 million federal grant.

“What we have done is look at what are some of the contextual factors at baseline that differentiate diabetes risk,” he said. Those factors can include such things as access to stable housing or transportation and proximity to convenience stores versus stores that provide more nutritious choices.

In Garcia’s case, it was a culmination of many things: her home life, familial culture and what she had available to eat as a kid.

Today, Garcia works as a caretaker for youth with autism, and she still feels her time spent in the program was worthwhile. The intervention helped her better understand how to stay healthy, she said.

“Even if I ate bad in the morning, that doesn’t mean I have to keep eating bad the whole day,” she said. “I can just pick up right where I started.”

Maintaining that can-do attitude is especially relevant now. One year ago, Garcia was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, which can cause fatigue, muscle weakness and weight gain.

Despite that diagnosis, Garcia remains positive.

“I’m getting back into a good routine,” she said. “And in the end, the payoff, it might not be overnight, and I think that’s the best payoff. The one that takes a little bit longer.”