TEMPE – It all started over a bowl of “medicinal menudo,” a term political cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz coined as part of a running joke.

Several years ago, during a convention at Harvard University, social scientist Gilberto Lopez took Alcaraz to a spot that served the Mexican beef tripe soup. Thankful for the meal – and the dish’s reputed abilities to alleviate hangovers – Alcaraz told Lopez, “I owe you my life.”

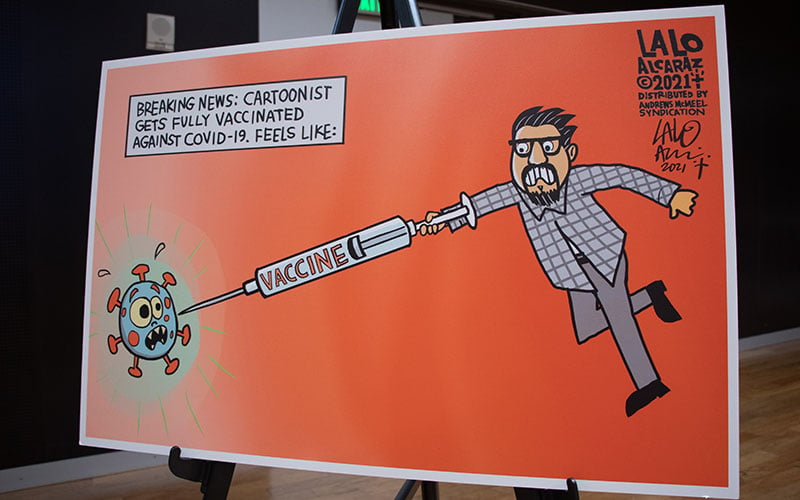

The menudo forged a bond between Lopez and Alcaraz, who has consulted on popular TV shows and films and was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2020 and 2021. During the pandemic, Lopez invited Alcaraz to collaborate on a Hispanic-focused education campaign about COVID-19 prevention and vaccinations.

Lopez, an assistant professor at Arizona State University’s School of Transborder Studies, launched the COVID Latino project with a goal of using art and social media to disseminate information – and counter misinformation – about COVID-19 throughout the Southwest.

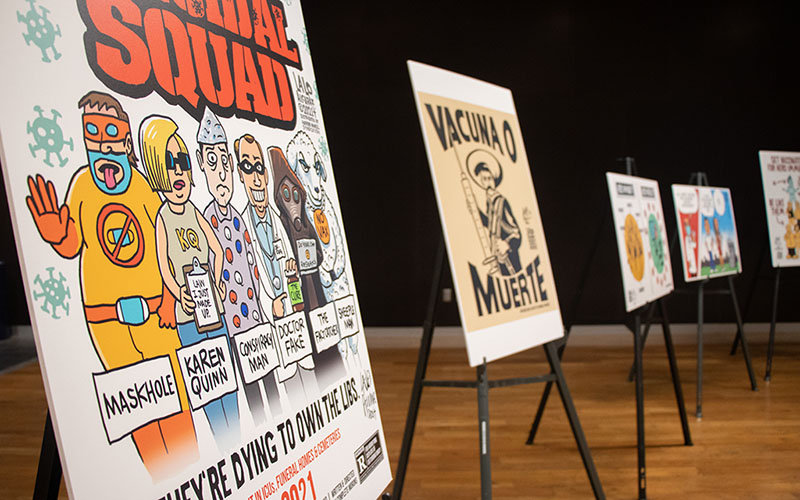

ASU’s School of Transborder Studies hosted an exhibit Sept. 16 of Lalo Alcaraz’s work on the COVID Latino campaign. (Photo by Mingson Lau/Cronkite News)

The effort brings together experts from Arizona and California’s Central Valley, home to many Hispanic farmworkers, and provides culturally relevant campaigns by way of the internet and social media.

The project so far has included animated public service announcements in Spanish and neighborhood murals to better connect with the hard-hit Latino population.

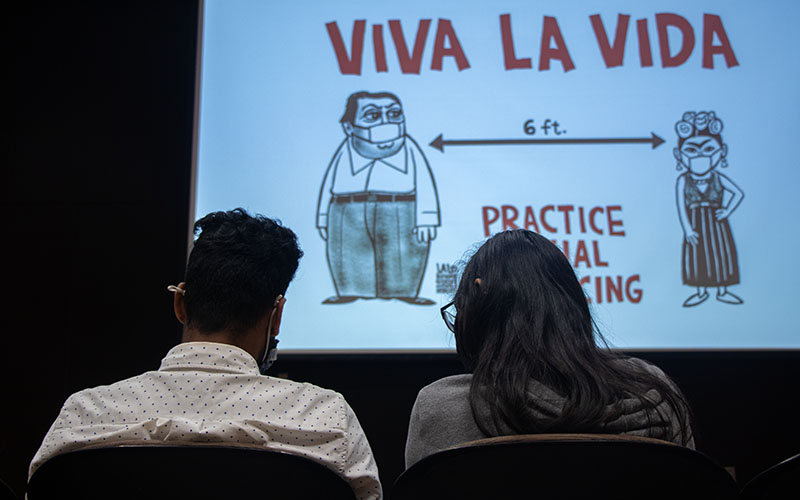

“Every few years, I’m lucky enough to get a new platform to expand my stuff and the reach of my work,” says Lalo Alcaraz. (Photo by Mingson Lau/Cronkite News)

Lopez said the project stemmed from his frustration over the type of information being circulated in rural, Hispanic communities – “very technical, very jargony information.” Through the collaboration with artists, Lopez said, the resulting pieces are easier to share online and will help make the topic more digestible.

“Humans are storytellers,” Lopez said, “and we’re telling stories in a way people understand.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hispanics are almost three times as likely as whites to be hospitalized due to COVID-19 and more than twice as likely to die from the disease. Nearly 87,000 Hispanics have died of COVID-19 in the U.S.

Alcaraz has been producing work focused on the Hispanic community and topics like immigration for over a quarter century, and Lopez said Alcaraz was eager to contribute to the COVID project with a series of cartoons encouraging Latinos to get vaccinated.

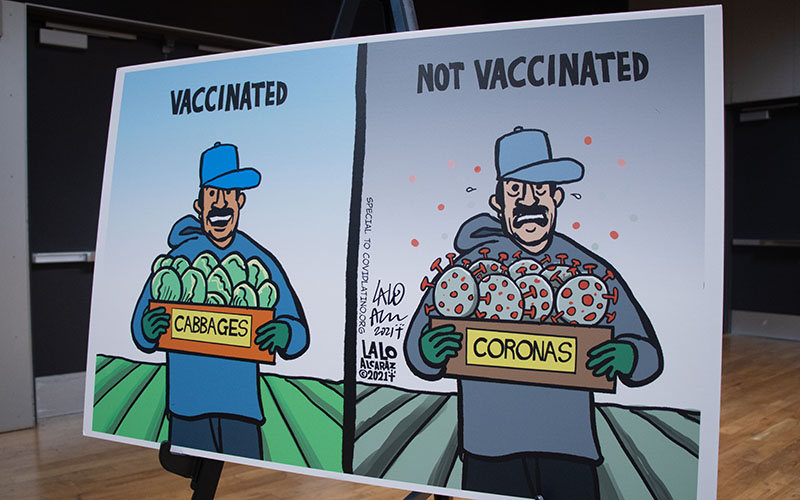

One illustration contrasts a vaccinated farmworker – looking healthy and holding a box of cabbages – with an unvaccinated worker who holds a box of red-spiked “coronas” – cabbage-size depictions of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

“COVID Latino is a … great effort to combat misinformation in the Latino community and combat vaccine hesitancy,” said Alcaraz, best known for his nationally syndicated comic strip “La Cucaracha” and his contributions as a cultural consultant for Nick’s “The Casagrandes” and Pixar’s “Coco.”

Alcaraz, who in April was named an artist-in-residence for ASU’s School of Transborder Studies, discussed his work during a recent exhibit in Tempe. The messaging is particularly important, he said, because “people are getting sick and dying from misinformation.”

When Jaleesa Minor’s professor recommended the exhibit, the ASU student did not recognize Alcaraz’s name but “for sure” recognized his work.

Growing up in Los Angeles, Minor said she saw his comics on her kitchen countertop and on social media. His style helped her connect with the Chicano community. The vibrant, “crazy colors” Alcaraz uses are reminiscent of the colors Minor grew up with: in the painted walls of people’s homes or the bright clothing used for festivals.

Minor, who is majoring in neuroscience with a minor in Chicano studies, said it’s vital that Latinos talk more about COVID-19 and how to safeguard against contracting the disease.

“It’s extremely important to have conversations like these at the dinner table with our friends and families,” she said, adding that her relatives are concerned about getting what they consider a hastily produced vaccine they know little about. “So much of my family … is very hesitant to trust something that the government is providing.”

Alcaraz, who’s the son of Mexican immigrants, remembers feeling ostracized while growing up in San Diego. He channeled that frustration into his artwork, a therapeutic practice that he hopes helps bring attention to an often overlooked group of people.

“If we are invisible, we can be demonized and be made to disappear,” he said. “And that’s wrong.”