Barbara Nelson likes to watch her Phoenix neighborhood from her south-facing window, where grayish stucco and sturdy tile roofs give the buildings a clean facade.

But the view inside her home is much less tidy. Nelson, who has lived here a year, is one of several residents at the complex who have risked eviction during the pandemic.

“The gentleman across the way, he works and he takes care of his daughter. He’s a single dad,” Nelson said. “And my neighbors that have the twins and their other daughter, that’s the same thing. … They pay as much as they can, but they’re facing eviction, too.”

Nelson lost her job in March when her 11-year-old son contracted COVID-19, and while she got her real estate license to make ends meet, she couldn’t show homes to clients after her truck broke down June 11.

At one point, Nelson said, she owed more than $5,000 in back rent and almost was out of options to pay it.

Across the country, as many as 1 in 5 renters say they have fallen behind on rent during the pandemic. For families who have no financial safety net to fall back on, the economic consequences of the pandemic have pushed them to the precipice of homelessness.

The Biden administration expected the $46.5 billion Emergency Rental Assistance Program, launched by Congress in December and March, to stave off the impending eviction crisis. But only about $5.1 billion had been distributed to Americans by states and localities through the end of July.

The administration had hoped a new federal moratorium on evictions would buy states and localities time to get the funding into the right hands, but the Supreme Court on Aug. 26 rejected the extension, clouding the future for tens of thousands of renters.

Nelson has been approved for rental assistance through Wildfire, an organization partnering with Phoenix to distribute emergency rental assistance funds, but the organization was slow to get the check to her landlord.

“It’s easy for you to say, ‘Try calling that number, try waiting on hold for an hour, calling back in another hour, calling back the next week, calling unemployment twice a week,’” Nelson said. “It’s all just been a struggle.”

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, even before the pandemic, 3 in 4 families were unable to get a Section 8 housing voucher, which is paid directly by a local housing authority, because of rampant underfunding.

“The pandemic put a spotlight on our nation’s housing challenges in a way that no other crisis in recent memory has,” said Ann Oliva, a senior fellow at the policy center. “And while newly funded eviction prevention programs are now getting fully underway, it is taking some time to get those funds into the hands of households and landlords who need it.”

A worsening housing crisis

When Jeff Yungman went to law school in 2004, he had big plans for his future legal clinic.

“There wasn’t a person there at school I didn’t tell, of the faculty or staff, ‘I’m here at school because I’m going to start a legal clinic at One80 Place,’” he said. “So everybody knew why I was there and what I wanted to do.”

One80 Place is the only full-service homeless shelter in Charleston, South Carolina, where it opened in 1984 under the name Crisis Ministries.

Now, Yungman’s colorful office sits in a converted 1950s home adjacent to the shelter, where he has worked for more than two decades.

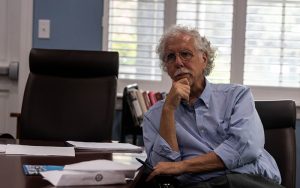

Jeff Yungman is the legal director of One80 Place legal services in North Charleston, South Carolina, which provides free legal representation for renters facing evictions. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

Despite the increase in demand for help, shelters nationwide operated at limited capacity to follow the safety guidelines set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Capacity at One80 Place has been capped at 50% since the beginning of the pandemic. Although Yungman said he has seen fewer people staying at the shelter, more people are coming in for legal concerns than ever before.

According to Oliva, for the first time since the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities started gathering data on the number of homeless Americans, more people are living on the streets than in homeless shelters.

“We have a renewed sort of outreach to try to reach people that need legal services that aren’t staying in One80 Place because of the fact we can’t keep as many people,” Yungman said.

Yungman helps homeless Charlestonians with a variety of legal issues, such as securing federal identification, attaining disability and unemployment benefits, and overseeing legal cases dealing with housing concerns.

One of his clients has been paying $650 a month for her trailer, which was condemned by Charleston County building inspectors months ago.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines any household that spends more than 30% of its annual income on housing and utilities as cost-burdened. SC Housing, the state agency for affordable housing opportunities, found nearly a quarter of South Carolina’s renters spent at least half of their income on housing and utilities as of March 2021.

“Pre-COVID, people would come in … 70% of their income was going to rent,” Yungman said. “We all would try to tell them, you know, we can get you maybe a plan to move out at a certain time and not have an eviction on your record, but … you can’t afford to stay where you’re staying.”

Magistrate Amy J. Mikell listens to an eviction hearing during a Housing Court hearing in Charleston, South Carolina, in July. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

Zillow found that the average rent across the nation rose by 2.3% from April to May of 2021, to $1,747 a month.

Oliva said experts knew a housing crisis was coming as early as January 2020, just as COVID-19 began to spread across the country. She said lockdowns and stay-in-place orders reduced opportunities for work and accelerated the oncoming housing crisis.

Ian Watterson, a housing lawyer and landlord for several small rental units in Charleston, said that for many mom-and-pop landlords, the pandemic-related economic downturn has made it much more difficult for them to maintain their rental properties.

“If they all get foreclosed on, it’s just going to reduce the rental stock and drive rents up further,” he said. “A lot of people are not renting anymore. They’ll sell the house or whatever. So when this is all over, you’re going to see a lot less rental units and higher rents.”

Emily Blair, the executive vice president of Austin Apartment Association, a Texas organization helping landlords, said that the increase in operational expenses related to COVID-19 and the lack of revenue due to the eviction moratorium has put landlords in a sticky spot.

“That takes away rental housing units from the community, which is not a good thing,” Blair said. “We want rental housing to be fully available for those who need it and who need that flexibility, who need that coming into a new market, who need that for affordability purposes.”

Essence Harrison watches her daughter, Amiya Belton, jump on Harrison’s bed at their apartment in Charleston, South Carolina. Harrison and Belton moved there in March after being evicted from their previous home. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

The lack of safety nets

Essence Harrison’s apartment on Gale Street in North Charleston is barren except for the child’s bedroom that sits down the hall behind the first door on the right.

“I’m not good at decorations. It’s not my forte,” said Harrison, who has lived in the two-bedroom rental with her daughter, Amiya Belton, since March. “But yeah, her room was the first room that I put up, I guess, as soon as I got this place. I was so excited for just her to have her room, finally. I put her bedsheets, her trolls, her table, her toys.”

It took Harrison more than five months to find a home where she could afford to raise her 3-year-old. The two-bedroom rents for $900 a month – the cheapest she could find.

When Harrison fell behind on the rent for the apartment where she had lived in June 2020, the federal moratorium did not save her from eviction. She spent four months living in hotels and taking Uber cars to work before an employee at One80 Place stepped in to help.

Amiya Belton washes dishes next to her mother, Essence Harrison, in their new apartment in Charleston, South Carolina. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

Even before the pandemic was declared in 2020, North Charleston had the highest eviction rate in the country, with 16% of tenancies ending in the renter’s removal.

In 2020, the neighborhood had a poverty rate of about 21%, more than twice as high as the national average as calculated by the Urban Institute. The poverty rate is even higher among North Charleston’s Black residents, who are the majority in South Carolina’s third-largest city.

According to the World Population Review, the poverty rate among Black residents in North Charleston is about 27%. It is more than 10% among the city’s white residents.

“During the course of the pandemic, we’ve seen the housing crisis really deepen in communities that have been historically marginalized,” said Alieza Durana, narrative change liaison at the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

Amiya Belton shows off her troll dolls in her new bedroom. Her room was the first to be decorated in their new apartment. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

According to a study focused on discrimination in evictions, people of color make up 80% of those facing evictions.

“Even controlling for all other factors – income, the home value and various other things you might sort of anticipate would be important factors – race was twice as impactful as any other factor,” said Kathryn Howell, co-director of RVA Eviction Lab in Richmond, Virginia.

Harrison was scheduled to start a new job managing a gas station two days after getting a positive test result for COVID-19 in July 2020. The company ultimately did not hire her.

Without savings or generational wealth to fall back on, she said healing financially from her losses took much longer than recovering her health.

“You don’t have anything to fall back on when you use all your savings trying to stay afloat while you’re sick,” she said. “And then you’re not sick anymore. That catchup is impossible. There’s nothing you can do.”

Harrison did not know where to start when it came to filling out paperwork and making phone calls. She tried to apply for unemployment, food stamps and COVID-19 relief but was told she was ineligible because she had made too much money the previous year.

There were several notices before Harrison’s landlord posted the final eviction date on her door. By then, she was $3,967 behind on rent.

“Just getting that last paper of them telling you what day you have to leave, I think that’s the hardest part of the eviction process,” she said. “And what it feels like is just, it’s like drowning, like drowning in paperwork.”

She said she didn’t try to fight the removal because she doubted she had legal grounds.

“It’s intimidating to have a company of any kind to send … you a court paper,” Harrison said. “I can’t afford to get anybody to defend me. Or who knows? And I probably don’t even have all the paperwork that they need for me to go to court, so I honestly didn’t even think about challenging them. I just left. I just did what I was told.”

It is common for tenants to “self-evict,” or willingly move out instead of appearing in court. In South Carolina, tenants being evicted are not automatically scheduled for a court hearing — instead they must call themselves.

“With landlord tenant laws, a tenant is at a disadvantage because the landlord is the person bringing the action against the tenant. And more often than not, a tenant does not know their rights. All they know is that their house, where they live, is in jeopardy,” Magistrate Ellen Steinberg said.

Eviction hearings in Charleston, South Carolina, take place in Housing Court, providing tenants and landlords the opportunity to speak and settle issues. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

A battle to prevent eviction

Brandon Harris wore his best suit to court on a Thursday morning in early July. Its bold plaid pattern, he said, boosted his confidence. He needed this hearing to go well.

Harris had already been planning on moving when he received an eviction notice from his corporate landlord. He was supposed to pick up the keys to his new apartment the day before his court date. Due to the pending eviction, his new landlord refused to hand them over.

“It’s just, just some difficult times. I got behind on rent. I was on disability leave without paying, and I just, I wasn’t able to maintain the bills,” he said.

Harris’ landlord claimed that other people were living in his apartment against the specifications of his lease, but Harris was several months behind on his rent. He had to leave his job at T-Mobile during the pandemic because of his chronic bronchitis, which puts him at increased risk for COVID-19.

Brandon Harris listens during his eviction hearing in Charleston, South Carolina. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

Ian Watterson was the pro bono lawyer appointed by the Housing Court to represent Harris in court that morning. Watterson and a representative for the landlord were able to agree on a date for Harris to move out without carrying out the eviction.

“I’m actually going to reach back out to that (new) landlord to have him call up here and let them know that everything’s settled,” Harris said. “We reached an agreement. So it’s a very promising place. I’m excited. I think I’ll be able to move in there.”

Watterson said Harris’ case is similar to many he sees. Usually, he added, landlords and tenants are able to reach an agreement without carrying out the formal eviction.

“There’s no great magic to this. It’s just negotiating and helping people through things,” Watterson said. “We have a pretty darn good success rate. We have learned a lot and are better at either mediating them or, if there’s a hearing, winning them.”

Housing Court is a collaboration of legal aid organizations in Charleston that provides legal representation to tenants facing eviction. The idea came from Jeff Yungman in the fall of 2018. As legal director of One80 Place Legal Services, Yungman had seen firsthand the effects of eviction and the lack of legal representation for tenants losing their homes.

Jeff Yungman, legal director of One80 Place legal services, provides free representation to people experiencing homelessness in the Charleston community. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

The first Housing Court session took place in October 2019. Since then, Housing Court has expanded into four magistrate courts, including Steinberg’s, with plans to add two more.

Landlords often do not want to evict their tenants, Steinberg said. The process is tedious – court hearings, painting, repairs – and it’s often easier for everyone to keep tenants in their homes, he said.

At first, landlords were hesitant to embrace the idea of Housing Court, feeling it offered an unfair advantage to tenants, the judge said. But over time they’ve come to recognize its ability to foster conversation.

“Landlords recognize that it works … when parties speak to each other,” Steinberg said.

But Yungman says that legal representation is not enough to alleviate the consequences of evictions. He wants to emphasize that the root causes of homelessness need to be addressed to mitigate the worst outcomes of the pandemic.

“Coming to terms with that,” he said, “The government has to provide some help for people in order to be able to afford the housing that’s available.”

Nicole Tillmon and Ryan Harvey, with their daughters Zahra and Amara Harvey, are months behind on rent and waiting for their rental assistance check to be sent to their landlord in Phoenix. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

Unknown territory

Ryan Harvey, who lives across the hall and up a floor from Barbara Nelson, has noticed changes at his Phoenix apartment complex.

Moving trucks in the parking lot and orange stickers from the constable’s office on neighbors’ doors have become frequent over the past two months. People, he said, were preparing for the ax to come down.

“Everybody knew the moratorium was getting ready to expire,” Harvey said. “Everybody’s aware that, you know, the safety net’s being pulled.”

The newest moratorium replaced a broader one that had been in place since Sept. 4, 2020, and expired July 31. The new moratorium, originally set to run through at least Oct. 3, was to prevent evictions due to COVID-related nonpayment of rent in counties with high transmission of the delta variant, which is about 90% of the U.S.

With the additional two months, states would have had more time to distribute the $46.5 billion allocated by Congress for the Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which has been tied up in bureaucracy. While some gains were made, the Supreme Court ordered the moratorium last week.

Harvey and his family were able to secure rental assistance from Wildfire, but the check has not been sent to his landlord yet.

Amara Harvey plays in her bedroom of her family’s apartment in Phoenix. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

Phoenix was allocated $51.1 million to begin the emergency program on March 8. But as of Aug. 3, a little under half that amount had made it into the hands of renters.

“The slow processing of rental assistance applications can be attributed to several factors,” said a July 27 report from the Aspen Institute, “including high documentation burdens, long payment timelines, and insufficient infrastructure for rental assistance support.”

In the same report, the institute estimated that 15 million renters owed more than $20 billion to their landlords.

But Yungman and some other experts said there are reasons to be hopeful.

“My assumption is that if a tenant has applied for ERAP funds and is still in the process of trying to get those funds given, everybody knows, of course, that that process is taking much longer than it should,” Yungman said. “I don’t think any of the four judges are going to evict somebody when there’s financial assistance pending.”

Ryan Harvey’s apartment in Phoenix, where he fell months behind on rent after losing his job during the pandemic. He recently was approved for rental assistance through Wildfire. (Photo by Kylie Graham/News21)

But despite receiving rental assistance, Harvey said, he’s unsure what the coming weeks will bring.

“Take one step forward, you’re taking 10 backwards, you know, so it is unknown territory,” he said, “I can’t tell you what the next month is going to look like. All I can say is we have to do the best we can day by day. We take it one day at a time.”

This report is part of Unmasking America, a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country. It is headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. For more stories, visit unmaskingamerica.news21.com.