The Round Valley Ensphere in Eager has multiple purposes. One day it might be hosting a high school football game, the next a popular car show. (Photos courtesy of Round Valley Dome Facebook)

PHOENIX – The twin communities of Eagar and Springerville, with a combined population of about 7,000, lie in Arizona’s Round Valley. The towns are nestled in the picturesque White Mountains, but Eagar has a man-made edifice that catches the eye almost as easily: a geodesic dome over 100 feet tall and 400 feet in diameter, looming on Butler Street behind a soda fountain and a Latter-day Saints church.

Daniel Heinemann, who manages the facility for Round Valley Schools, said he remembers the first time he saw the dome.

“When I was moving into this town, I drove over and I thought, ‘What is that building?’” he said. “And now I run it, so I’m a little biased.”

The Round Valley Ensphere – so named for the atypical connector design implemented by the dome’s architects – purports to be the only domed high school football stadium in the country. But to focus on that label would be to sell it short. After all, it can fit more people than the combined population of the two towns it serves.

“It has absolutely provided a space to hold larger events that we just would not get to hold,” said Karalea Cox, communication director for the Eagar stake of the LDS church, “whether those are church-related or whether they are larger, kind of economic-type events.”

In terms of athletics – its stated purpose – the dome plays host to football, basketball, wrestling, volleyball, track and more, providing significant value as an indoor facility in a region beset by snow and strong winds. But the dome has also housed devotionals, car shows, quilt shows, model airplane contests, band camps, graduations and carnival – to say nothing of evacuees from the region’s grave fires.

In 2002, the Rodeo-Chediski fire ravaged eastern Arizona, even prompting a visit from President George W. Bush. But evacuees from towns affected by the blaze had a place to stay in the dome, with its restrooms, showers and copious space.

The Round Valley Ensphere is a geodesic dome over 100 feet tall and 400 feet in diameter and hosts a variety of events. (Photo courtesy of Round Valley Dome Facebook page)

Jerry and Susan Hathcock had just renovated their home in Eagar and wanted to use the extra space to house evacuees from Show Low. They knew where to go to offer their hospitality.

“We knew that this mass amount of people were coming into the dome, and so we just went to the dome in search of somebody,” Jerry Hathcock said. “We had no idea who or how many that we would end up with, but we were going to offer our home for someone to stay there.”

They found a couple of visibly overwhelmed parents standing with four or five children (as it turned out, the total number of children was in the double digits) and invited the Butler family to stay in their new trailer and spare bedrooms. For the duration of the evacuation, the kids shared chores and the parents split cooking duties. It was a neat arrangement that began in the dome.

“The people that came from Show Low and surrounding areas on that particular event, they were grateful to have a place to stay,” Susan Hathcock said. “When you’re staying in a place with millions of other people, it’s not ideal for anybody, honestly, but it served a purpose, as it has in numerous other events and activities.”

Or, as Round Valley superintendent Travis Udall puts it: “We take it for granted. We’re spoiled rotten.”

Udall added he doesn’t know if he would have thought of building a dome in Eagar, but his fellow superintendents certainly wish they had it.

There was a time when Round Valley was on the same footing as other nearby school districts. Gary Davis, a retired superintendent for Tucson Electric Power whose family has a long history in Apache County, said he watched high school gymnasiums at St. Johns, Snowflake and Blue Ridge fall behind the curve as he grew up.

“They were nice gymnasiums when they were built, but when we got into the 80s, they were just so small,” Davis said, “and these communities were small way back in the 50s, 60s and 70s, but there was quite a bit of growth in this area.”

Davis said the community had propositions putting forth both a dome and a gymnasium for approval – this was on the 1987 ballot. When both passed, the dome took precedence.

Chip Shay was a partner in the architectural firm now known as SPS+ Architects, which had designed Northern Arizona University’s Walkup Skydome, and was enlisted by then-superintendent Robert McKenzie to produce a dome for Round Valley.

The damage from the Rodeo/Chediski fire in 2002 was widespread, and some evacuees ended up at the Round Valley Ensphere. (Photo by David McNew/Getty Images)

Shay said the dome was borne of a confluence of environmental forces: both Flagstaff and Eagar were situated about 7,000 feet above sea level on the Colorado Plateau, the Round Valley football program had just produced the NFL’s Mark Gastineau and saw a chance to build momentum, and there was a national movement toward closed stadiums.

Like the Walkup Skydome, Round Valley’s dome would be composed of wood beams. Both would shelter their teams from snow, uncommon elsewhere in Arizona. And Shay explained that in a region of the state prone to fires, timber could char and self-insulate, preventing damage, whereas something like steel would become weaker if exposed to heat.

“It’s inherently more efficient, more cost-effective and more renewable,” Shay said, ”but they didn’t use the term green back then because the LEED didn’t exist.”

The Round Valley dome would not be a carbon copy of its northern counterpart. For one thing, it would also include a new, patented “handsome six-pointed star” connector to join the beams, called the Ensphere. It also needed to be smaller while still housing as many sports as possible. This meant Shay and company had to innovate to get the indoor track approved.

“There’s not enough room to have a slowdown lane at the end of the track,” Shay said. “So what we did is we put a huge, roll-up door – we needed one anyway to get access for the building at the lower level – we located that right at the end of the track.”

The facility, well-suited for nearly every Round Valley high school sport (Shay excludes baseball), cost over $11 million in taxes. But TEP, which was responsible for 90% of property valuation in the Round Valley, also had to pay 90% of the taxes, per an Associated Press report from 1991. TEP sued the school district, claiming the dome didn’t meet the definition of a “school building” because of possible non-school uses, but lost in 1990 and had to foot the bill.

“It was a real blessing for these small communities to have that power plant, that station there, for employment plus to have things like this,” Davis said, “because I don’t think we could have ever built it without TEP’s presence with their property tax.”

One popular event in the Round Valley Ensphere is Chrome in the Dome, which showcases classic cars from around the state. (Photo courtesy Round Valley Dome Facebook page)

He added that the prospective gymnasium wouldn’t have cost much less than the dome anyway. And despite TEP’s resistance, Davis said it eventually embraced the dome, hosting a non-school event of its own: a company party that drew employees from as far as Tucson.

This event presaged the many community and corporate uses that awaited the dome in the future. Udall, the current superintendent, said that the cost of maintaining the dome prevents it from being a profitable facility. Instead of trying to “nickel and dime” locals for use of the dome, he said, he has relinquished a lot of control to residents in an attempt to build support for the school district, easing the financial burden on many community events.

One main event is Chrome in the Dome, an annual car show that harnesses the talent of local students. Organizer Mike Campbell said indoor car shows are rare. He estimated that his show draws about half the population of the Round Valley, and they certainly appreciate having a roof.

“We had snow the first year we did it, and we didn’t know it,” he said.

Campbell, a retired lineman who runs the event with his wife Kathi, said that the woodshop, auto shop and welding shop from Round Valley High School help design trophies, and graphic design students make artwork and print shirts. The money from the event goes toward trade education at the school.

“The only reason I made it through high school was the vocational programs,” Campbell said, “I wasn’t a book person, I was a hands-on type person… Knowing that they still have them here and not all schools have them, it’s near and dear to my heart to make sure the program keeps going and we can assist in any which way possible.”

Tom Gaylor, an Air Force veteran who leads the Phoenix Model Airplane Club, said the venue is the best in the state for flying his model planes, even if the altitude requires an adjustment from the fliers.

“We have had flights in the dome upwards, I think probably, of 40 minutes,” he said, “on the very, very light indoor free-flight airplanes.”

As part of this year’s contest, club members taught middle school science students to build a rubber model called the “Mountain Lion.” The competitors will return to the dome in 2022 for the indoor national free-flight model airplane competition.

Other events in the dome are similarly integrated with school curricula. Participants in the Round Valley Quilt and Fiber Arts Show, hosted in the dome in 2018 and 2019, teach a free quilting class for middle schoolers.

“The art of sewing, this stuff’s being lost,” Udall said. “Not here in Round Valley.”

Much like Chrome in the Dome, the quilt show helps fund scholarships for graduating students. More than that, it brings people together, said Billye Wilda, co-organizer and owner of Quilter’s Haven.

“I think the most rewarding part is having an exhibit in a small community that everybody can take part in,” Wilda said. “And then a plus on that is the gals that work so hard on their quilts and enter them, and when they get a ribbon they are so excited.”

Out-of-town events like concerts don’t work as well, Udall added. This is in part because they lack a recurring community commitment.

“The acoustics and the design of it are not set up for it very well,” he said. “Usually the promoters want huge, huge amounts of money. They’re there just for a one-time shot and then they leave.”

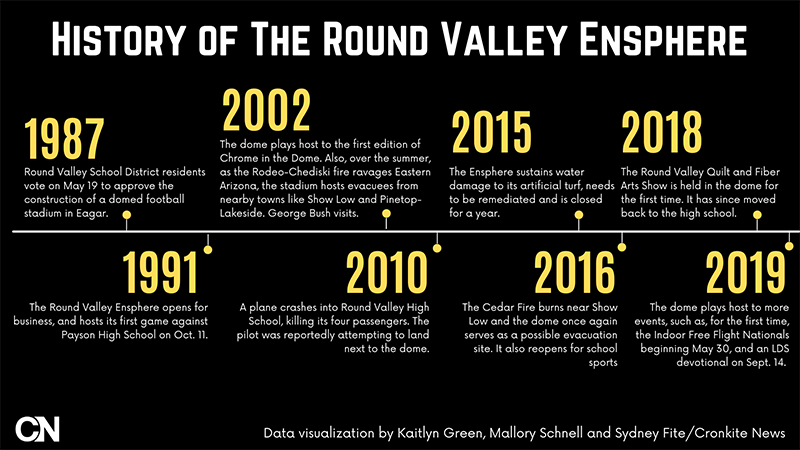

(Data visualization by Kaitlyn Green, Mallory Schnell and Sydney Fite/Cronkite News)

The dome’s principal purpose, of course, is athletics. The dome may be smaller than its NAU predecessor, but Udall said it’s still large enough for football and volleyball games to take place together, with bleachers set up between the two, or to host varsity, JV and freshman basketball games simultaneously.

The Ensphere’s sheer size has also proved useful in times of disaster. The dome housed evacuees during the Rodeo-Chediski fire in 2002, Shay said, when it received a visit from President George Bush.

But in 2015, the dome itself succumbed to the elements. It suffered water damage to its synthetic turf in the face of heavy rain. Heinemann said the building closed for about a year, during which time football moved outside to the shadow of the dome, and basketball relocated to the middle school. He added that a company called Sagebrush had to come in for remediation.

“When that was lost, it actually made people realize how important the dome is to the community,” Udall said, “and instead of complaining about it all the time, about costs and whatnot, they actually started to appreciate it.”

Udall granted that the dome has flaws such as its lack of a proper drainage system, and the expenses of using propane to heat it in the winter. But it proves its value through its contributions to local businesses, local officials said.

“The communities of Springerville and Eagar are lucky to have such a magnificent facility for all,” wrote Springerville Mayor Phil Hanson Jr. in an email, “including students of RVHS, local businesses, and the community as a whole.”

The prevailing sentiment surrounding the dome is awe. Udall said even Arizona Cardinals players were impressed when they visited for a youth camp. And FieldTurf installers who work at NFL stadiums across the country didn’t know what to make of the Ensphere.

“These guys have seen everything, and the first time this crew came in, they were flabbergasted by it,” Udall said.

Heinemann spends a lot of his time around the dome. But every time someone new comes in – students from neighboring schools, tourists headed into New Mexico – he sees a reprise of what he experienced on his first visit to Eagar.

“A lot of the students, teams and stuff that come into this place, the first thing they do is they walk out, they look up, and they’re just: ‘Oh, wow.’”

Quilt shows are among the many events the dome hosts. “It has absolutely provided a space to hold larger events that we just would not get to hold,” said Karalea Cox, communication director for the Eagar stake of the LDS church. (Photo courtesy of Billye Wilda)