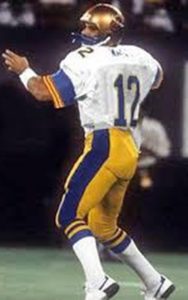

Before Rick Neuheisel coached the Arizona Hotshots at Sun Devil Stadium, he played quarterback for the San Antonio Gunslingers, a team in the USFL that also had a franchise based at the Tempe stadium. The USFL is returning in 2022. (Photo by Christian Petersen/AAF/Getty Images)

PHOENIX – The United States Football League of the mid-1980s brought sports fans a three-season whirlwind of front-office intrigue, roster turnover and eventually litigation, occasionally interrupted by some decent spring football.

Before imploding in spectacular fashion in 1986 amid a failed move to the fall, the league, broadcast on a fledgling ESPN, introduced future stars like Steve Young and Herschel Walker to fans nationwide.

It also gave untapped markets like Jacksonville, Memphis and of course Arizona an early taste of professional football – even if it wasn’t always of the highest quality.

“They thought pro football was so cool,” said Neil Balholm, a wide receiver for the 1983 Arizona Wranglers and 1984 Denver Gold, “even with guys like me out there running around.”

Brian Woods, founder of The Spring League, announced in June his intention to work with Fox Sports and bring back a new iteration of the USFL in 2022. In the intervening decades, the NFL has created barriers to entry for spring football: It’s become more of a year-round enterprise, from the February scouting combine to July training camp, and more markets have received teams. Numerous spring leagues have come and gone, rarely completing one season, let alone three.

Wranglers alumni just hope this new USFL has leaders who know how to build patiently, from the ground up.

“I hope they learn that you got to stay within yourself, you got to be patient, you got to let the league develop,” said Alan Risher, a quarterback for the 1983 and 1984 Wranglers. “And the fan is just not going to spend good money seeing a bad product. You can’t buy somebody’s love.”

When the inaugural rosters arrived at their first USFL training camps back in 1983, the young, impressionable, borderline-NFL-caliber players had few doubts about the league’s viability. As Rick Neuheisel, the San Antonio Gunslingers quarterback and later longtime college head coach, put it, “When you’re 23, you think everything’s 10 feet tall and bulletproof.”

The Wranglers players saw their enthusiasm reflected in the eager Arizona fans.

“Obviously it was a very fertile market,” Risher said. “They’d never had a professional team in the Phoenix area before, and the Arizona Cardinals were not even a thought at that point in time.”

The Wranglers drew over 45,000 fans for their season opener on March 6, 1983. The opener was a disappointing loss, but the following week, they rallied from 17 down in the fourth quarter to knock off the George Allen-coached Chicago Blitz.

“That was considered the greatest comeback in USFL history,” Risher said, “led by yours truly.”

But the team faded down the stretch, winning only three of 16 remaining games. And they soon found themselves once again connected with the Blitz in the history books. Chicago owner Ted Diethrich, who was based in Arizona, decided to take over the Wranglers from their previous owner Jim Joseph, selling the Blitz to James Hoffman, and exchanging the teams’ rosters in their entirety.

It was a borderline-comical display of instability, of the sort that has defined spring football leagues before and since.

“It’s the greatest, weirdest, most awesome sports trade of all time, with no close second,” said Jeff Pearlman, sports writer and author of the USFL tome “Football for a Buck.”

Despite the sweeping nature of the trade, it still managed to be inconsistently applied. Risher ended up staying with the “new Wranglers” for a 1984 season in which they reached the championship game. Though Risher said the trade meant a better product for the fans, Pearlman emphasized that it undermined the league’s credibility.

“You’re not just selling football, you’re selling almost like a relationship between a fan base and a city,” Pearlman said, “and if you get rid of the team after one season, it’s very hard to make a guarantee that the same team you have in year two is going to be there in year three.”

Mark Keel, a tight end who went from Arizona to Chicago as part of the trade, said the wealth of sports teams in Chicago prevented the Blitz from getting much attention there.

“A lot of what we had in Arizona with the community feel, and the local feel, was definitely gone in a big city like Chicago,” Keel said. He rediscovered that feeling in football-crazed Jacksonville in 1985, which he described as “like being in Tempe, tenfold” and reminiscent of the NFL.

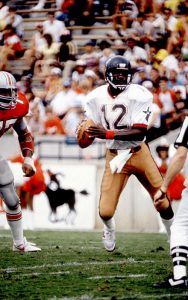

Dan Manucci’s football career included a spot with the USFL’s Arizona Outlaws. (Photo courtesy Dan Manucci)

For his part, quarterback Dan Manucci found out just before Blitz training camp that, without his knowledge, he had been traded from Chicago to the Memphis Showboats and then cut.

He ended up working for Motorola as a recruiter, before eventually returning to what had become the Arizona Outlaws in 1986. The fourth season was slated to take place in the fall, at the behest of owners led by Donald Trump who wanted to force competition against the NFL. But the season was canceled, and the league released its players in August after the USFL was awarded nominal damages of $1 in an antitrust suit against the NFL.

“It was such a good thing, and then all of a sudden, you got too many cooks getting in the kitchen and guess what happens?” said Manucci, a radio talk show host and quarterback trainer in the Valley. “The broth gets spoiled.”

Neuheisel agreed, citing a different allegory.

“Fan interest at least in a portion of the towns was really strong, and it could have continued to be,” he said, “had we been able to just be more of a tortoise type of thing, rather than the rabbit trying to sprint out and get to the finish line too quickly. Steady wins the race.”

The USFL has been followed by other even shorter-lived attempts at spring gridiron football, including the Alliance of American Football (AAF) and two versions of the XFL. The Arizona Hotshots of the AAF, coached by Neuheisel, played at Sun Devil Stadium like the Wranglers. The league came onto the scene with good TV ratings, to the point that SB Nation proclaimed an NFL partnership virtually “inevitable,” but shut down due to lack of funding after just eight games.

Some well-known names stopped in the Valley during the USFL days, including former NFL quarterback Doug Williams, who played for the Outlaws. (Photo by Michael Minardi/Getty Images)

“The vibe was force-fed,” Manucci said. “They tried to put a 10-pound ball in a seven-pound hole. It just didn’t work.”

Neuheisel remains a firm believer in spring football.

“For the players, it either gives you opportunity or closure,” he said. “For the coaches, you continue to get to teach. … And for the fans, you get behind a team, and you get to enjoy the spirit of great competition.”

Shortly after the USFL’s announcement, XFL Newsroom reported that the new league has the rights to many of the old USFL team name trademarks. Indeed, The Spring League LLC had filed for the Arizona Wranglers trademark, for example, on March 3. Multiple alumni touted the nostalgic value of these brands.

“In my mind right now, and you know, maybe it’s the heartstrings,” Keel said, “but they all sound like they’d be good names to just bring back.”

However, USFL alumni and experts broadly agreed that Arizona, now having the Cardinals, may not be the right choice for a spring market. Pearlman called it “not really meant to be.”

“They could never overcome that hurdle,” he said, “that people didn’t want to sit in 105 degrees to watch an A-minus football league.”

Balholm, Keel and even Neuheisel – despite his Hotshots experience – said that markets without existing pro teams would be ideal for a spring league. That’s the opportunity the old USFL afforded to Arizona.

Balholm said he’s seen hundreds of fans turn out in Humboldt County, California, when his son travels there for summer collegiate baseball. He thinks a spring league could target larger markets that show this same passion for football.

“San Diego doesn’t have anything now, right?” Balholm said. “In Utah, maybe Salt Lake, or something like that. Albuquerque, New Mexico. I mean, you’d have to kind of look at these mid-to-higher marketplaces, where they just don’t have much.”

The key, for those who watched the old USFL’s collapse from up close, is for the new league to provide financial and competitive stability in its ownership. That means no more team-for-team trades or brazen moves to the fall.

“The players will show up and play – that’s not the issue,” Manucci said. “It’s just how you execute it, but you got to have the money behind it. If not, then it’s kind of like déjà vu all over again, right?”