WASHINGTON – Federal officials want to greatly expand habitats for black-footed ferrets in Arizona and possibly into neighboring states, but the endangered animal, once thought extinct, still faces several hurdles, experts say.

Those include a mysterious drop in ferret numbers at a site in Arizona in 2012, after years of gains, and the ferrets’ dependence on sharply declining numbers of prairie dogs, its main food source.

Conservationists, who have worked for the past 25 years to bring the ferrets back from the brink of extinction, said they are still “in a learning phase” about the animals but working to understand hurdles they could face before releasing them into the wild.

“Reintroducing ferrets, we want to get back in that game again, but we need to secure the prey and secure the habitat,” said Holly Hicks, a small nongame mammal biologist with Arizona Game and Fish Department.

The department’s “been in the game a long time,” she said, and has seen the black-footed ferrets make a steady comeback since recovery efforts began three decades ago from a population of just 18 remaining animals. By last year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had been able to release a total of 5,544 ferrets at 30 sites in the western U.S., Canada and Mexico since efforts started.

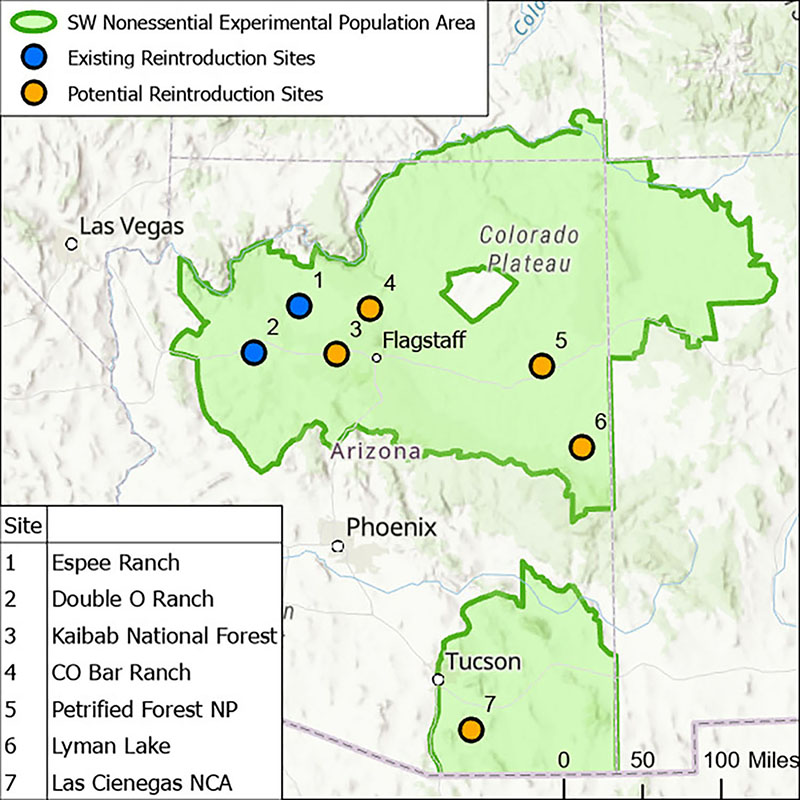

Conservation officials have identified five potential sites in Arizona that they believe have the necessary elements – including a sufficiently large prairie dog population – to support the introduction of endangered black-footed ferrets. (Map courtesy Center for Biological Diversity)

But the service, concerned that any threat to the one site near Aubrey Valley in Arizona could wipe out the state’s population, wants to spread ferrets in the state over a wider area. It unveiled a plan in late June identifying 40.9 million acres across most of Arizona and parts of New Mexico and Utah that could be suitable habitat.

“The goal of the Black-footed Ferret Recovery Plan is to recover the ferret to the point at which it can be reclassified to threatened status and ultimately removed from the list of endangered and threatened wildlife,” the service said in a June 25 post in the Federal Register.

In Arizona, the notice identified parts of the Kaibab National Forest, the Colorado Bar Ranch, Petrified Forest National Park and land near Lyman Lake as suitable for reintroduction because they appear to have sufficient numbers of prairie dogs to support the ferrets. Some would require approval by area tribes, which are considering the plan.

Another site, at Las Cienegas National Conservation Area in Coconino County, is contingent upon growth in the prairie dog population there.

“The key is to allow them (prairie dogs) to increase where black-footed ferrets could exist, and where we would not be eliminating many prairie dogs,” said Michael Robinson, senior conservation advocate with the Center for Biological Diversity.

But not everyone is keen on seeing a growth in the number of prairie dogs, which some farmers and landowners consider “a nuisance.”

The Arizona Farm Bureau Federation’s policy on prairie dogs says they “are causing serious deterioration of farm and rangeland and are a danger to horses and their riders.”

“Prairie dogs are also a potential carrier of deadly diseases,” the policy says, adding that federal and state organizations need to “help in the control of these pests.”

With prairie dogs as the ferrets’ only prey, experts caution against releasing black-footed ferrets until prairie dog populations stabilize. Other challenges include ensuring disease will not wipe out prairie dogs, and consequently the ferrets.

After their reintroduction in the Aubrey Valley in northwestern Arizona began in 1996 with the release of 40 ferrets, their numbers grew steadily until they peaked in 2012 – but have mysteriously declined ever since. One theory is that diseased prairie dogs could have sparked the ferret decline, but experts are still studying the possible causes.

“A lot of times when you see this (a decline), you assume it’s plague, but we’re not seeing normal signs of disease,” Hicks said.

Prairie dogs have a history of spreading disease, and consequently, were subjected to a policy of mass removal years ago. That, in turn, threatened black-footed ferrets, experts say.

“The major reason they (ferrets) became endangered is because of the massive reduction in prey through the systematic poisoning of prairie dogs beginning about 100 years ago,” Robinson said.

While there is significantly less poisoning than before, experts say prairie dog numbers are still in flux. Robinson said prairie dog instability would “disrupt part of their ecosystems, and there can be ramifications we don’t consider.”

“We need to appreciate and love all of it, including the black-footed ferret, which needs our love,” he said.