PHOENIX – Danielle Edwards, a registered nurse and mother of two, nearly died because of risky medical mistakes when she gave birth to both her children.

During her first pregnancy in 2014, she gained 20 pounds in one week, a sign that her blood pressure was too high. Edwards said she was not given proper medication, putting her at risk for seizures and liver failure.

In her second pregnancy in 2016, Edwards said she experienced alarming fits of nausea and dizziness. In the delivery room, her placenta detached from her uterus, cutting off oxygen to her son and causing severe bleeding.

She knew something wasn’t right but felt brushed off by hospital staff.

“When they realized that it had been going on for probably quite some time during my labor and delivery, that was kind of traumatic for me because I had been telling them something was wrong,” said Edwards, who declined to name the hospital.

“They had to put me on oxygen and put me on my left side and all these things. I just felt so terrible that I thought I was going to die. I thought he was going to die.”

Edwards – who’s now 33 and director of nursing at Pima Medical Institute in Tucson – and her husband had planned to have four children but stopped after two because of safety concerns.

“If you asked my husband, he’ll say, ‘We couldn’t have had more kids because I didn’t want you to die. I didn’t want to raise my kids alone.’”

Edwards’ experiences inspired her to serve as the patient advocate on the new Arizona Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, to “make sure that hospitals are working to ensure education and safety of our moms out there.”

The AIM Collaborative brings together 33 hospitals across Arizona to help combat pregnancy-related deaths and address underlying causes using strategies based on evidence.

Danielle Edwards, 33, in a portrait taken in Marana, Arizona. Edwards experienced severe complications while bearing her two children. “If you asked my husband, he’ll say, ‘We couldn’t have had more kids because I didn’t want you to die. I didn’t want to raise my kids alone.’” (Photo by Alberto Mariani/Cronkite News)

The collaborative launched its first program in May, providing hospitals with so-called “pregnancy bundles” – a list of practices for both medical staff and patients – with a goal of reducing complications of hypertension by 20% over the next 18 months.

“This is a gift to the mom, the care that’s delivered to them which is based on the evidence, meaning research and national guidelines,” said Vicki Buchda, vice president of care improvement at the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association.

The U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality among developed countries, according to a 2020 report by The Commonwealth Fund, which points to a lack of providers and inadequate postpartum care.

About 700 women die each year in the U.S. as a result of pregnancy-related issues, and about 60% of those deaths are preventable, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Black and Indigenous women are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women, and those disparities increase with age, according to the CDC.

In Arizona, Native American women are four times more likely to die from these types of complications than white women – the highest rate across the state.

With these deaths in the spotlight in recent years, federal and state officials have pushed for legislation to protect mothers.

In 2018, former President Donald Trump signed the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, which supports state maternal mortality review committees in tracking maternal deaths.

Vicente and his Leticia Garcia sit for a portrait in their Phoenix home. They became advocates for better maternal health care after their daughter died during childbirth in 2018. (Photo by Alberto Mariani/Cronkite News)

The next year, Arizona lawmakers established the Advisory Committee on Maternal Fatalities and Morbidity to review data collection efforts and develop recommendations.

Buchda said the AIM Collaborative is the first partnership of this size in Arizona that not only tracks data related to maternal health but actively works to find solutions.

The pregnancy packages are designed to provide consistent health care protocols to help hospitals better prepare for, recognize, respond to and report on any complications caused by high blood pressure.

For example, facilities will receive standards to spot early warning signs for preeclampsia and evaluate pregnant women with hypertension, as well as protocols for educating patients about the signs of hypertension and preeclampsia.

The goal is to quicken response times when problems arise and integrate extensive followup care to ensure the safety of mothers.

About 7% of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. are related to hypertensive disorders, according to the CDC. Other factors include cardiovascular problems, infection, hemorrhage or embolisms.

Dr. Andrew Rubenstein, head of obstetrics and gynecology for Dignity Health Medical Group at St Joseph’s Hospital in Phoenix, praised the AIM Collaborative approach of bringing together multiple hospitals and a variety of expertise to improve maternal health.

“Without this, we have really failed to really address some of the health care issues that have been plaguing the ever-rising maternal health care crisis,” Rubenstein said, noting the U.S. ranks “lowest among the high income countries for the parameters of maternal health, disparities and racial inequities and the social determinants of health.”

Pregnancy-related complications have been rising and affect tens of thousands of women every year, the CDC reports. Health experts aren’t entirely sure why but point to women giving birth later in life and preexisting conditions, such as obesity.

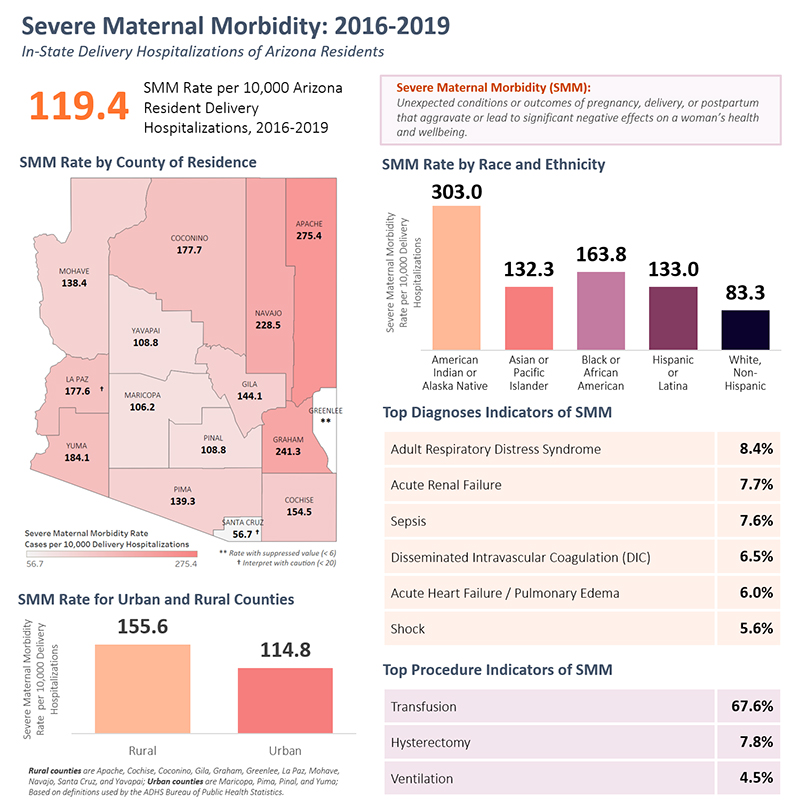

In Arizona, about 900 women a year experience a severe complication during labor and delivery, and women with chronic hypertension are almost three times more likely to suffer from complications, according to a report by the Arizona Department of Health Services.

In addition to having higher death rates, Native American women have the highest rate of complications related to pregnancy in the state.

Severe Maternal Morbidity (SMM) is the unexpected conditions or outcomes of pregnancy, delivery or postpartum that aggravate or lead to significant negative effects on a woman’s health and well-being. (Source: Arizona Department of Health Services)

Two tribal hospitals are involved in the AIM initiative: Whiteriver Indian Hospital on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in eastern Arizona and Tuba City Regional Health Care on the Navajo reservation.

Rubenstein said that in order for all communities to be integrated into the AIM effort, hospitals and other health organizations need to support culturally appropriate maternal care, including the use of doulas – women without formal medical training who provide support to mothers during the birth process.

Indigenous communities, in particular, have turned to doulas to try to combat maternal mortality.

“This is all about inclusivity,” Rubenstein said. “The ability for Arizona AIM to allow us to really integrate into those communities has been one of our goals.”

Breann Westmore, maternal infant health director for the Arizona chapter of March of Dimes, a national nonprofit that advocates for moms and babies, said the collaborative also is examining other underlying factors that affect maternal health, such as income, reliable transportation and familial support.

“Throughout the effort, a lot of our partners have begun to look at the social determinants of health and look at it with a health equity lens,” she said. “We know care is not equitable in different populations, and we’re working to compensate for that.”

Westmore was among those who advocated for passage of SB 1040, which directs the state health department to conduct studies to improve maternal mortality rates.

The bill is known as “Arianna’s Law” in memory of Arianna Dodde, who died at 23 after giving birth to her third child in 2018. During labor and delivery, Dodde suffered a torn uterus, which led to internal bleeding and eventually cardiac arrest.

Her father and stepmother, Vicente and Leticia Garcia, were blindsided by the tragedy because Dodde had previously given birth to two healthy girls, Ava, 6, and Analisa, 4.

Vicente Garcia believes that if his daughter had been monitored more closely, “she would still be here.”

“Before this happened, I thought (maternal care) was great. But it’s been a tough slap in the face with the reality that it’s not so great,” he said. “There are holes in our system that need to be fixed. There’s a lot of room for improvement.”

The Arizona AIM initiative plans to launch additional care bundles targeting other medical conditions, including obstetric hemorrhage and blood clots as well as obstetric care for women with opioid addictions.

“I think the collaboration is fantastic,” Vicente said. “(The organizations) see there’s an issue and they want to address it. It sounds like there’s going to be some really positive, practical changes that are going to hopefully reduce the amount of mothers that are lost, that are injured, that go through adverse effects.”

Leticia Garcia said she’s grateful there will be more information about maternal health to help encourage people to have important conversations and raise awareness about the potential dangers that still exist around giving birth.

“It was horrible,” she said of losing her stepdaughter. “But to have something beautiful come out of it, like perhaps saving other people this heartache, what else could you ask for?”