Editor’s Note: This story is part of an ongoing project to highlight Black athletes who have broken barriers and made lasting contributions to Arizona sports.

PHOENIX – He was a trailblazer. An athlete. A civil rights activist. Yet 67 years after he stepped away from baseball, the full story of John Ford Smith’s life remains untold.

“You go online, you know, it says he was here, he was here, he was here. But you don’t know how he got there,” said Phil Dixon, a highly regard author and historian of the Negro Leagues. “So, a lot of his life is a mystery.”

——–

On a tree-lined street in the Alhambra neighborhood of west Phoenix, in a tan house set back on the curve of a road, sit the daughter and grandson of Smith, who pitched for the Kansas City Monarchs and was the only Arizonan to play in the Negro Leagues.

They reflect on the life of Smith, who started his professional baseball career in 1939 with the Chicago American Giants but saw little action with them in his lone season there. He spent the 1940 season with the Indianapolis Crawford before leaving for the Monarchs in 1941.

His baseball career took a break while he served in the Army Air Corps from 1942 to 1945.

Ford Smith’s daughter, Jackie Garner, is proud of her father’s legacy with the Negro Leagues. (Photo by Abby Sharpe/Cronkite News)

“My dad was in the military, he finished as a lieutenant. He spent most of his time during World War II in England,” Jackie Garner said. “And he led those folks that had to drive those bombs to the airfields. And they had to drive with no lights, and in the fog a lot of times at night, because you didn’t want them (the enemy) knowing that they’re moving things.”

After finishing his military service, Smith, 27, returned to Kansas City. In the 1946 Negro World Series, he started Game 2 and left with a three-run lead after the sixth inning. Satchel Paige entered as the relief pitcher and gave up six runs that cost the Monarchs the game. The Monarchs lost the series, but the details remain an important historical bookmark.

Conversations about diversity in sports have picked up in recent years. On Dec. 16, 2020, Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred announced that statistics and records from the Negro Leagues would be recognized in Major League Baseball history.

Smith’s numbers will be among them. He ended the 1948 season with a 10-5 record, the fourth most wins in the Negro Leagues. Smith also was fourth in ERA that season, posting a 2.64.

In 1948, Smith traveled to Puerto Rico to play in the Puerto Rican Winter League. There, he went 13-6 and led the league in wins. He was more than just a pitcher. He also played first base and the outfield and was a standout hitter.

The whole family went to Puerto Rico that winter, and Garner recalled her mother showing her own baseball skills in the stands.

“My dad hit a fly ball that happened to come between the space of these backstops up here. And my mother got it,” Garner said. “She said, ‘Oh, I’m used to that.’ So that was, that was really funny. She caught us a fireball.”

On Jan. 28, 1949, Smith and Monte Irvin became the first two Black athletes signed by the New York Giants, now known as the San Francisco Giants. Smith was assigned to their minor league club, the Jersey City Giants, where he played two seasons.

“There was a period of time that he had pneumonia,” Garner said. “And so that also slowed him down with the Giants’ system, because he went to the majors and played one day. I think that’s when he got sick, or at least that’s what they said.”

That her father got sick so soon after reaching the majors did not escape Garner’s attention. Global health organizations recognize social determinants of health, conditions that affect health risk and outcomes. Studies show that racism and discrimination can negatively effect health.

Smith reached the majors two years after Jackie Robinson, but more than a decade before MLB was fully integrated. He surely faced racism and discrimination, as most Black players did at that time.

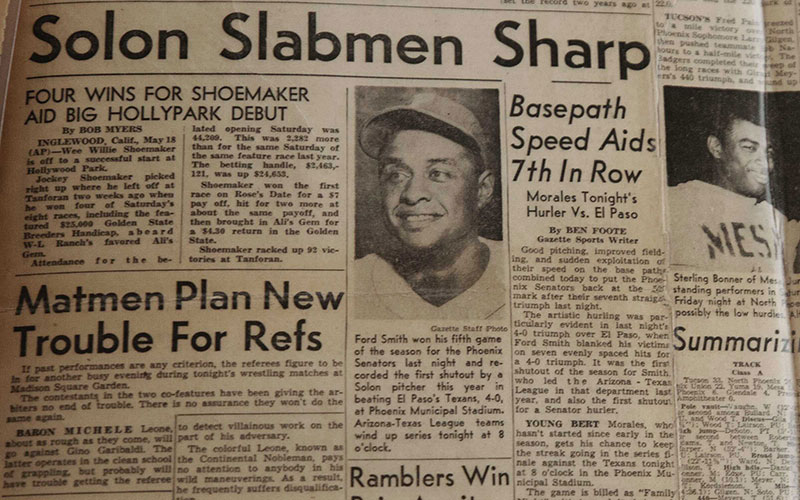

In 1952, he returned to his hometown of Phoenix to play for the Phoenix Senators in the Arizona-Texas League. His last year of professional baseball was in 1954 with the El Paso Texans.

“He never reflected that he felt cheated or never felt, never demonstrated that,” Garner said. “But I just think in his head, he had a long view.”

A family man

Smith was more than a baseball player. He was a beloved husband and father, his family says.

Garner described him as mostly quiet, pleasant, occasionally boisterous and slow to anger. And thoughtful.

“The unique thing about him was Christmas,” she said. “He never went Christmas shopping before Christmas Eve. He knew exactly what he wanted to get. … He (would have) something in mind for my mom that he wanted me to look at. And it would just blow us away that he could just go and come back with his packages, and everything was beautiful.”

Garner also appreciated his advice, like the time she was a sophomore in college and wanted to take a year off. She went home on a break and had that conversation with her father.

“My dad was just driving. And he said, ‘Well, you could do that. But I would hope that you wouldn’t do what I did and not go back.’ It was like Dad spoke and it went all through me,” she said. “And somehow I got it. But that’s the way he would talk. He was very gentle.”

Buck O’Neil, a Negro Leagues legend and longtime advocate of the game, was with the Monarchs at the same time as Smith. Garner said O’Neil would sometimes show up to family dinners.

“He and John, John O’Neil – Buck O’Neil – would replay games from 30 years back and could tell you, ‘Well, you remember when I was, when he did this?’ ‘Oh, yeah, that’s right,’” Garner said. “I mean, they just could replay the game like they had just played it the day before. That was fascinating.”

After his baseball career, he stayed in Phoenix and, Garner said, “did a bunch of things.” He worked in a cotton gin, then ran Eastlake Park for many years. Later, he became the equipment manager at South Mountain High School, and helped the baseball players, especially pitchers, on the side.

Smith later served on the Arizona Civil Rights Commission, which was established in 1965 and had the authority to enter into agreements with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, issue subpoenas, survey discrimination in Arizona and submit an annual report detailing the commission’s work to eliminate discrimination.

He eventually became the head of the commission, Garner said, and his work there “meant everything to him. Because I mean, he lived what needed to happen. He lived that.”

Segregation was still rampant in the 1950s and ’60s. Garner said her father received orders to serve in the Korean War, which didn’t sit right with her because the military was segregated.

“By then I understood what the disparity was,” she said. “I was so livid that my father was being called back to fight for this country, when he didn’t have all the benefits of this country.”

Garner was adamant that her father should not have to serve in Korea. She said she screamed at God in her head, saying she didn’t want her father to go.

Her prayers were answered a few days later.

“Within two days, his orders were canceled. But when it was canceled, I was like, ‘Oops,’” Garner recalled. “I just said, ‘Thank you.’ Because I just, that just to me was not fair. Just not fair.”

A deeper issue

After news broke that the Negro Leagues would be recognized in MLB history, Garner told ABC15 that her father would be “quite pleased” with the announcement.

“But he would also say it’s about time,” Garner said. “I think that’s what it’s really about time to do now, to have open dialogues, and be open about our history. What you read in most books about how we got here. The pun is intended: It’s whitewashed.”

MLB’s mission in recent years has been to increase participation in baseball and engage younger fans, as it sees itself losing its connection with the Black community. About 8% of MLB players are Black. In Garner’s eyes, the lack of Black baseball players is due to two things: team owners going elsewhere, like Latin America, to recruit players, and the bigger appeal of football and basketball in the Black community.

Ford Smith’s grandson, John Ford Smith III, said it’s important that baseball reaches out more “to the communities, like more programs for children and (different) ethnicities.” (Photo by Abby Sharpe/Cronkite News)

“There were Black kids who were beginning to play football and basketball. They had equal, more equal access with those sports and particularly those that paid big money,” Garner said. “They started focusing on earnings. You make more money in football, you can make more money in basketball. And so they went to that, gravitated to those sports.”

Garner mentioned the lack of places to play baseball, especially for those who live in cold climates. Access to the game is an issue MLB continues to address, including creating Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities, also known as RBI, in 1989 to provide disadvantaged youth a chance to learn and play baseball. RBI is in more than 200 cities nationwide and about 150,000 girls and boys participate every year.

Another aspect of baseball that makes the game inaccessible to everyone? Cost.

According to the Kids Play USA Foundation, parents pay an average of $381 for one child in one sport for one season. Although it remains cheaper to play than many other sports, it can still be a deterrent.

A lack of diversity throughout professional baseball – managers, coaches and the front office remains an issue. Across the league, meaning employees of all 30 clubs, front offices, the commissioner’s office and MLB media entities, 7% are Black. Sixteen percent are Latino or Hispanic, and 3% are Asian. Women make up 20% of jobs across MLB.

Diversity is important, but it should happen authentically and with a purpose, Garner said.

“What is your intent? Why are you doing this?” she said.

John Ford Smith III, Ford Smith’s grandson, agrees that diversity is important in baseball, and MLB can advance its mission by sharing its history and the difficulty associated with reaching the major leagues.

Smith said MLB increasing its presence in communities would also go a long way.

“I think that if they reach out more to the communities, like more programs for children and (different) ethnicities, no matter if it’s Cuba or anywhere in Japan, it doesn’t matter,” Smith III said.

Bringing up the history of baseball is one way to promote diversity, Smith said. MLB recognizes one player from the Negro Leagues once every year: Jackie Robinson. This is good, but is it enough?

“You’d figure that you’d have more about Roberto Clemente, you’d figure they’d have like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, maybe even the first Japanese player, which I don’t know when that was. I mean, we don’t even know that,” the grandson said. “That’s the problem with the major league.

“They’re focusing more on what Blacks have gone through, but at the same time you need to focus on who else came in and who else became an All-Star and who else broke all those records. I think that’s the key, to be a lot more diverse in their actual message to getting more minorities in pro sports and everything, especially if it’s baseball or football or whatever.”