Colorado River water managers could be pulled back to the negotiating table as soon as next year to keep the watershed’s biggest reservoirs from declining further.

The 2019 Drought Contingency Plan was meant to give the U.S. and Mexican states that depend on the Colorado a roadmap to manage water shortages. That plan requires the river’s biggest reservoir, Lake Mead, to drop to unprecedented levels before conservation among all the Lower Basin states – Arizona, Nevada and California – becomes mandatory. California isn’t required to conserve water in Mead until the surface drops to 1,045 feet above sea level.

Lake Mead is currently at its lowest level since it was first filled in the 1930s, at roughly 1,069 feet. Lake Powell, which straddles the Arizona-Utah line, is projected to hit its lowest level this summer.

“Right now, we’re in an unprecedented time,” said Michael Bernardo, the federal Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Basin river operations manager.

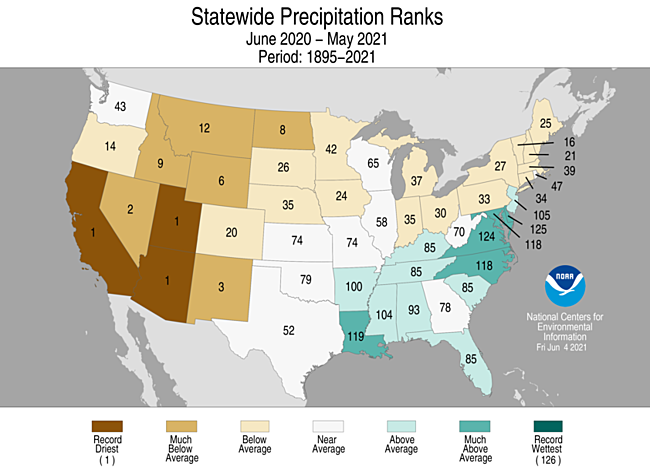

The 12 months from June 2020 through May 2021 were the driest on record in three of the basin’s seven states: California, Arizona and Utah. That same period was the second driest for Nevada and third driest for New Mexico.

Another consecutive dry year will amplify the alarm bells already clanging throughout the basin, Bernardo said.

“Should 2022 be as dry as 2021 is currently, I think you’ll start to see a lot more activity in the basin states and the senior principals in the federal government to get together to work on the next proactive agreement to reduce risk further,” he said.

Climate change is altering the water cycle in the vast Colorado River Basin. Rising temperatures diminish Rocky Mountain snowpack, increase evaporation from streams and reservoirs, and sap moisture from the soil, which combines to reduce the region’s overall water supplies. A failure to reduce demand at the same magnitude has left the Southwest facing imminent shortages.

The Upper Basin Drought Contingency Plan recently was put in action to develop guidelines for reservoir releases to be made to prop up Lake Powell. A program called demand management, which would create a market to pay large users to not draw their legal share of water, is in the concept phase and has not been approved. Water officials in Colorado have assured skeptical farmers that the program’s establishment is “not a foregone conclusion” and that participation would be voluntary.

The Drought Contingency Plan was billed as an overlay to the Colorado River’s existing guidelines, established in 2007 and set to expire in 2026. Without the drought plan, federal officials said during its development, the system that supplies 40 million people in the Southwest faced risk of failure.

“I think that it’s way too early to say whether the drought contingency plans work,” Bernardo said. “I don’t think it has gotten a chance to work yet. And I think we’re going to have to go into these lower lake elevations to actually see these increased water savings contributions.”

A first-ever federal water shortage declaration in the river’s Lower Basin is expected in August.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial content.