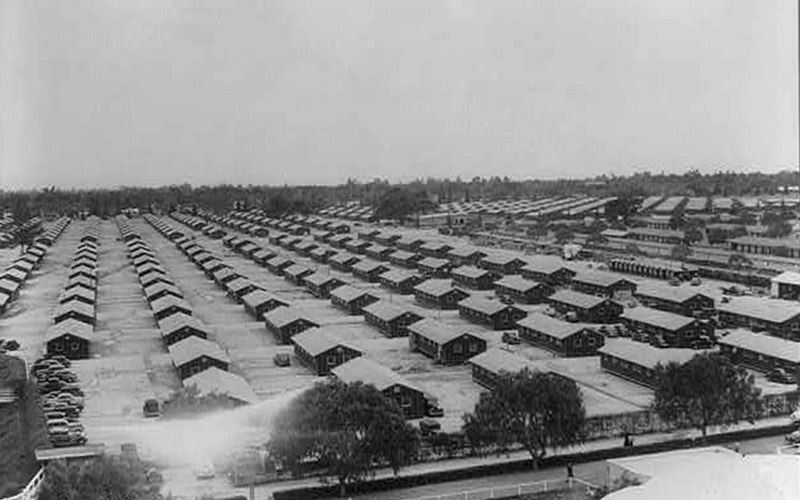

Two Japanese families are shown at a Salinas, California, assembly center. Fred Korematsu was sent to a California center for processing to a Utah internment camp. He fought the relocation all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court but lost; his sentence was vacated years after the camps were shuttered and called out as a national shame. (Photo courtesy of U.S. War Relocation Authority/Library of Congress)

Known during World War II as a reception center, according to Library of Congress archives, this California center was a type of holding facility for those of Japanese descent who were to be relocated to internment camps. (Photo courtesy of Clem Albers/U.S. War Relocation Authority via Library of Congress)

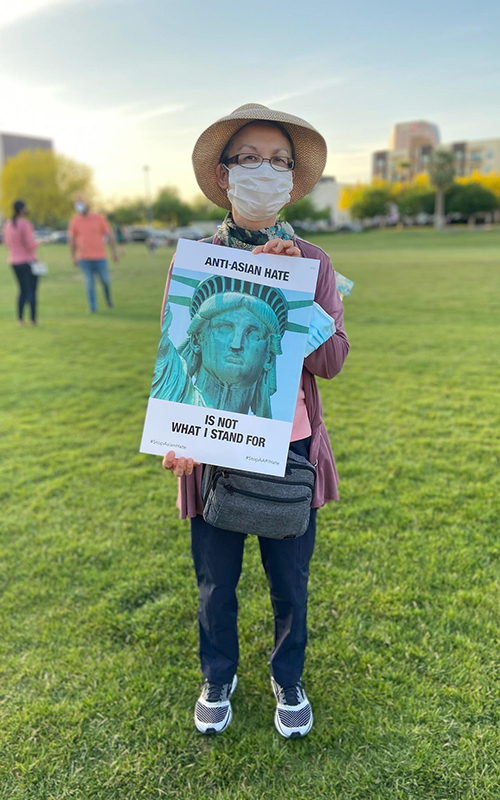

Midori Hall, 78, was born in a Japanese internment camp shortly after her family was moved there in 1942. She laments that racial divisions are still wide. “Whatever happened to kindness, loving one another regardless of the color of one’s skin, working together, peace and more?” (Photo courtesy of Midori Hall)

Nearly eight decades after the United States forced Japanese Americans into prison camps during World War II, Arizona will recognize the efforts of a man who turned his pain into a lifetime of activism for equity and inclusion.

A new state law designates Jan. 30 as Fred T. Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution. Arizona joins 10 other states in honoring the activist on his birthday.

The bipartisan-supported honor comes as harassment and hate crimes against people of Asian descent rise, as Asian Pacific Heritage Month is celebrated in May, and education around challenges to democracy for underserved communities still falls short.

Still, Korematsu Day is not a national or state holiday like Memorial Day, President’s Day or the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, as Korematsu’s daughter notes.

“It’s not a holiday, and that’s part of the problem,” said Karen Korematsu, founder and executive director of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute in San Francisco. “I want this day to not only honor my father, but as a point of education, and to focus on our civil liberties in the Constitution.”

For others, Fred T. Korematsu Day serves as a time to advocate for a cause. Donna Cheung, who chairs the civil rights committee for the Japanese American Citizens League in Arizona, says the commemoration is especially significant now.

“It’s something that especially resonates at the present moment,” Cheung said of Korematsu Day. “Not only should Asian Americans speak out against what is happening to the community, but also about elected leaders.”

All people should join in honoring Korematsu’s legacy, she said.

Donna Cheung, who chairs the civil rights committee for the Japanese American Citizens League in Arizona, says the naming of Fred T. Korematsu Day in Arizona is especially significant now. She was among advocates and protesters who rallied against hate mongers in Arizona and elsewhere. (Photo courtesy of Jennifer Chau)

“Other people who are not Asian American need to speak out against that type of violence against the community,” she said.

As a young man in his 20s, Fred Korematsu was among about 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent who were sent to war relocation centers starting in February 1942 under President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Japanese Americans were held at 10 internment centers, mostly in Western states – including the Gila River and Poston camps in Arizona – based on a government policy of fear and racism after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, plunging the U.S. into war.

Korematsu, with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, went to court to fight his relocation to a Utah center but lost his case when the Supreme Court in 1944 ruled the relocations were a necessary war measure.

After the war, he lobbied in Washington, D.C., to get reparations for internment camp survivors, and he fought for the rights of federal prisoners. He was honored in 1998 with a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

A Boy Scout in suburbia, then a life upended

Fred Korematsu, born in 1919 to Japanese immigrants, grew up in Oakland, California. He was raised in a Presbyterian family, went to church every Sunday and participated in Boy Scouts, according to Karen Korematsu.

But there was discrimination, too, she said, recalling her father’s stories.

“When he was in high school, he wanted to have his hair cut by a real barber,” she said. “My father starts walking in and the barber says, ‘Hey, boy, what do you want?’”

He asked for a haircut. The white barber responded, “I don’t cut the hair of people like you. Get out and don’t come back.”

There were other indignities, like being refused service at a diner. Then came the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Koretmasu was 23 in 1942, when he was ordered to go to an incarceration camp in Topaz, Utah, that housed 8,000 people. He was arrested May 30, 1942, for violating the order and was held in a San Francisco County jail. Four months later, he was convicted of violating the order, prompting the American Civil Liberties Union to file suit on his behalf as a test case against Executive Order 9066.

Korematsu lived with his family in the Topaz camp from 1943 to 1945. The Supreme Court ruled against him in December 1944, calling the mass relocation a military necessity.

His case was reopened four decades later, after critical documents hidden by the federal government were revealed, according to the Korematsu Institute website. The documents showed that no acts of treason had been committed during the war to warrant incarceration. A federal judge vacated Korematsu’s conviction on Nov. 10, 1983.

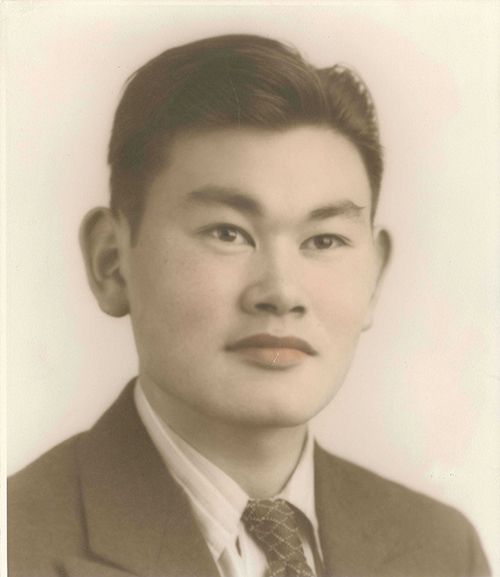

“Fred was not interested in a pardon from the government; instead, he always felt that it was the government who should seek a pardon from him and from Japanese Americans for the wrong that was committed,” his daughter, Karen Korematsu, founder and executive director of the Fred T. Korematsu Institute, says on its website. (Photo courtesy of Fred T. Korematsu Institute)

“Fred was not interested in a pardon from the government; instead, he always felt that it was the government who should seek a pardon from him and from Japanese Americans for the wrong that was committed,” Karen Korematsu says on the institute’s website.

He continued to work as an activist, becoming a member of the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations, one of three national organizations pushing to get help and financial support for Japanese Americans who had been forced into the camps.

He advocated, successfully, for the Civil Liberties Act on Aug. 10, 1988, which required that each camp survivor get a presidential apology and $20,000 compensation. The act was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Medal of Freedom in 1998. The activist died in 2005 at age 86.

A day of recognition in some states, but a national holiday still waits

Gov. Doug Ducey signed Korematsu Day legislation in April. Senate Bill 1800, sponsored by Sen. Sonny Borrelli, R-Mesa, had passed unanimously in the Senate and House.

“Fred Korematsu’s bravery and dedication to gaining justice for himself and others is admirable, and reflects the character of our nation,” the governor said in a statement.

In addition, Ducey added Arizona to the national designation of May as Asian Pacific American Heritage Month to honor the “military service, civil service, educational contributions and community leadership of Arizonans of Asian and Pacific Islander heritage.”

Eleven states, including Utah, Hawaii, New York, South Carolina and Michigan, have established Jan. 30 in the name of Korematsu, according to the institute.

Karen Korematsu wants others to learn about the life her father led and what he means for the Asian American community. She’s taking that knowledge to the classroom.

“We’re pushing for ethnic studies (in schools) in different states,” she said.

“The California Board of Education just passed our ethnic studies model curriculum for high school students because high school students didn’t even have that much (education on ethnic backgrounds in the U.S.) in their state curriculum.”

Learning about baseball, cramped quarters and illness in relocation camps

Such a curriculum could reveal the history of the camps, from the baseball games played for a sense of normalcy to the cruelty of the loss of their previous lives because of Executive Order 9066.

Arizona’s two internment centers, at Gila River and Poston, were open from 1942 until the war’s end in 1945. About 13,500 Americans were held in two camps at Gila River and fewer than 18,000 were held in three camps at Poston, according to internment camp data.

Midori Hall, 78, was born in a camp at Gila River shortly after her family arrived there in August 1942. Hall said her family has mixed views of the camp – the family had food and a place to stay. But poor conditions led to health problems for many, including Hall’s older sister.

“She was in the camp, and in the following year, she contracted tuberculosis,” Hall said. “They (the family) were affected when they were in horse stalls and fairgrounds that were not healthy places.”

Richard Matsuishi was 4 when he arrived at Poston in February 1942. He’s 83 and lives in Sun City after retiring as a dentist.

“Our family had one room that was about 10 feet by 20 feet, and five of us had to live in there,” he recalled.

They hung makeshift barriers in the room for a sliver of privacy.

“The protections (protective sheets) that were inside our room were made by my father and mother,” he said. “They strung up some rope and put some blankets up to get some privacy.

“Shower facilities were just open barracks with shower nozzles coming out of the walls. The latrines were open all the way, with no privacy.”

In the years since the camps were shuttered, the Korematsus and other human rights advocates have revealed the forced internments as a national shame.

In 1983, the federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians declared Executive Order 9066 unconstitutional and fueled by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Hate crimes, failed government policy and a repeat of history

Discrimination against the Asian American Pacific Islander community persists, most recently in connection to the COVID-19 pandemic. President Donald Trump and others insisted on calling the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 “the Chinese virus.”

Anti-Asian violence is on the rise. On April 5, a gunman opened fire on several massage parlors in Atlanta, killing eight people, including six women of Asian descent. The suspect will be charged under hate crime statutes, prosecutors announced May 11. Asian Americans also have been attacked on the street in multiple cities.

Thirty-two percent of Asian adults say they have feared someone might threaten them, and 81% say that violence is increasing, according to an April survey by the Pew Research Center.

According to Stop AAPI Hate data from March 29, 2020, to Feb. 28, verbal harassment and physical assault collectively made up more than 79% of hate-fueled incidents. According to the site’s national trends, Chinese made up the largest ethnic group to experience hate-driven incidents at 42.2%. Korean and Vietnamese followed, at 14.8% and 8.5% respectively.

Fred T. Korematsu fought his forced relocation to an internment camp for Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. Arizona joins 10 other states in designating Jan. 30, his birthday, as a day to commemorate the civil rights activist and his battles for democracy for all. He is about 21 in this undated photo.(Photo courtesy of Fred T. Korematsu Institute)

In many cities, especially larger cities in New York and California, hate-crime rates have surged.

According to data from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, hate crimes in New York were up 223% for the first quarter of 2021 compared to the first quarter of 2020. In Los Angeles, hate crimes were up 80% for the same period.

Cheung said history seems to be repeating itself.

“For elders who grew up in Arizona, especially in Glendale during the 1930s, they experienced farm bombing,” she said. “Many of the Japanese Americans were farmers, and they experienced that type of violence where their farms were being bombed because of white farmers who just didn’t like the competition.”

Cheung learned about such incidents from her time volunteering at the Japanese Senior Center in Glendale. She recounted the story of Kaye Takesuye, who was the target of bombs placed in yards and irrigation ditches.

“They were sleeping in their bedrooms and a bomb shattered the glass of the window,” Cheung said, adding that Takesuye “was always so grateful her mom had put up the curtains to hold the glass in place so that it wouldn’t cut her.”

She draws similarities between the hate incidents of the 1930s and 1940s to what’s happening now.

“Anti-Asian sentiment may be based upon economic competition,” Cheung said. “But along the way, people in positions of power – elected officials – do not push back against them.”

Midori Hall said racial tension is rising for other reasons.

“I believe that the present emphasis on racial divisions, even teaching it to young children in the classroom, adds fuel to the fire,” she said. “Whatever happened to kindness, loving one another regardless of the color of one’s skin, working together, peace and more?

At least two memorials have been established in honor of those imprisoned in Arizona.

The Poston Memorial Monument in Parker, erected in 1992, honors the 17,867 people who were forced there, according to Visit Arizona.

Chandler has built a history kiosk spotlighting the Japanese Americans who were ordered to the Gila River center, where remnants of the past remain.

Perhaps the best way to remember the past, Cheung and Hall said, is to learn from it and build awareness of what happened nearly 80 years ago.

“His fight for justice was not for just himself, or the Japanese American community, but for all Americans,” Karen Korematsu said of her father. “He was concerned about Americans in general, because he didn’t want something like the Japanese American incarceration to happen again.”