Phoenix police don’t follow Fe’La iniko on social media, but he knows they’re watching.

“They’re pretty hip to Instagram,” the racial justice activist said. “Sometimes they’ll pop up in my story views.”

Iniko, whose given name is Milton Hasley, often uses social media to share fliers on upcoming protests or speak out against police violence. So when officers surrounded his car last summer while he was leaving a demonstration against the killings of George Floyd and Dion Johnson, iniko worried he might have been targeted in advance for his views. As a handful of cop cars trained their spotlights on him, he was careful to keep his hands visible as he placed them on the steering wheel, a video he posted on Instagram shows.

“Try not to look threatening,” he remembered thinking.

Hours later, iniko was booked into jail and charged with two felonies and two misdemeanors, all of which were later dropped. He was one of hundreds of Phoenix protesters arrested during last year’s demonstrations against systemic racism and police brutality, which were met with an aggressive police presence and a number of controversial charges from prosecutors.

Police reports and court records would later reveal that police surveilled some of the protesters on their social media accounts during the summer and fall.

It was a year that would see Black Lives Matter demonstrations and civil unrest followed by anti-lockdown rallies, election protests and the fatal Jan. 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol. In the Capitol insurrection, law enforcement officials scoured social media platforms, sweeping up photos, videos and comments that have helped to identify, arrest and charge hundreds of people.

This form of online policing has gained traction as a means of addressing the looming threat of domestic terrorism. But many agencies — including the Phoenix Police Department — work under barebones guidelines when monitoring online activity.

Privacy and civil liberties experts say the standards for conducting social media surveillance are riddled with policy gaps, paving the way for uneven treatment of different political opinions and leaving police with overly broad powers that can stifle free speech and encroach on the public’s privacy.

Chip Gibbons of Defending Rights & Dissent, a free-speech advocacy organization, described authorities’ unconstrained surveillance of social media as the “Wild West” of policing.

“Looking at everyone’s Facebook to make sure no one is doing anything wrong is not acceptable,” Gibbons said. “The police should not go unregulated or unchecked on social media just because social media is public.”

A review of more than 100 police and court documents and policy reports, and interviews with more than two dozen activists, policy experts and law enforcement officials revealed:

- The Phoenix Police Department’s policy, created in 2013, doesn’t include standards for approving the use of social media in investigations. It doesn’t specify which officers can work on social media surveillance, how they’re trained, or how they can flag, share and retain digital evidence. And it doesn’t detail any protections for civil liberties or accountability procedures.

- Phoenix police monitored the social media accounts of some Black Lives Matter activists ahead of protests last summer and before there was any suspicion of wrongdoing.

- Activists across the political spectrum say they know or suspect their social media accounts are monitored by Phoenix police — either because their posts are identified in their case files or, like iniko, because they see the department’s official account in their Instagram Story views.

Phoenix police declined to be interviewed for this story, but they did respond to written questions by email.

Asked whether police monitored protesters’ accounts in 2020, spokesperson Sgt. Andy Williams wrote, “The Phoenix Police Department continuously monitors activity within our state. We have a responsibility to vet any information about potential criminal activity to help ensure the safety of all community members.”

Social media: The ‘Wild West’ of policing

Hundreds of police departments nationwide use social media to gather information.

Of the more than 500 law enforcement agencies that responded to a 2016 survey by the Urban Institute and International Association of Chiefs of Police, 70% reported using social media for “intelligence gathering for investigations.” And 60% said they had contacted a social media company to obtain information to use as evidence.

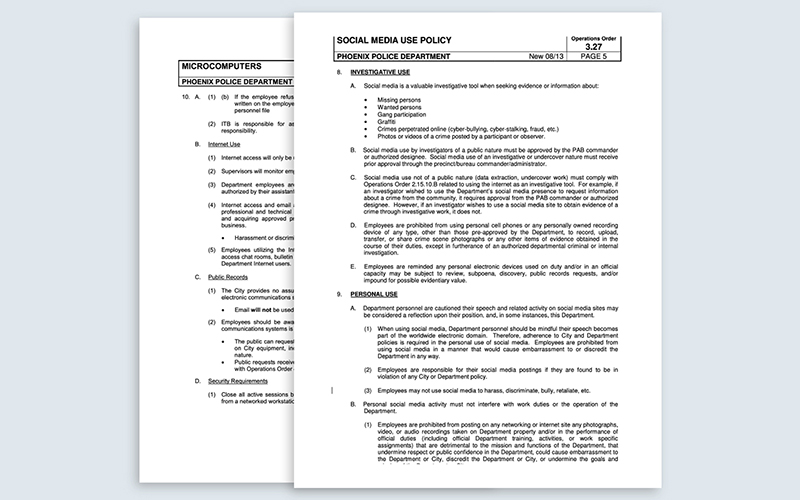

The Phoenix Police Department’s 253-word policy on social media use outlines few restrictions and guidelines for online surveillance. (Graphic by Jimmy Cloutier)

But experts who have studied the practice say not many departments have detailed guidelines on social media use.

The Phoenix Police Department created its 253-word policy in 2013 and hasn’t updated it since. It outlines six reasons for surveilling social media accounts: to find missing persons, to seek evidence on wanted persons, to locate gang members, to track down graffiti taggers, to capture online crimes such as cyber-stalking, and to gather evidence from photos or videos of crimes posted online.

The policy is “very vague,” said Rachel Levinson-Waldman, deputy director of the Liberty & National Security Program at the Brennan Center for Justice.

“If I were an officer that was looking to the policy to really give guidance about what I could and couldn’t do with social media, there wasn’t a lot of concrete information there,” she said.

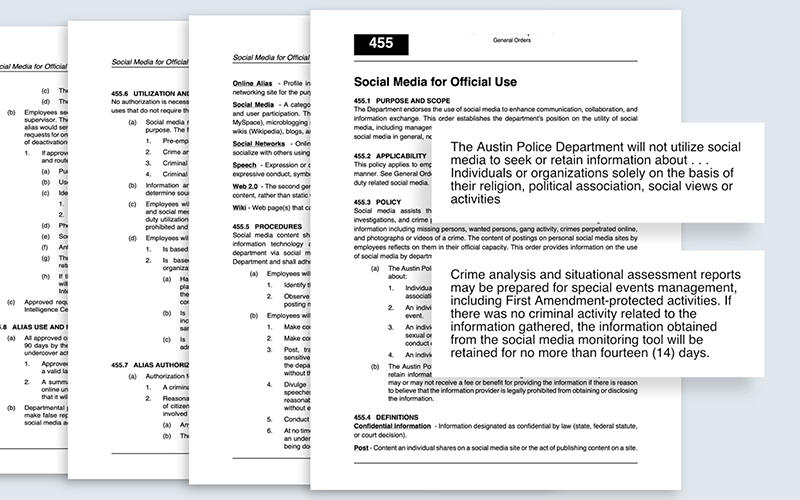

By contrast, Levinson-Waldman said the guidelines from the Austin Police Department in Texas are some of the strongest she’s reviewed. That policy specifies who can conduct surveillance, outlines First Amendment protections and describes appropriate uses of undercover accounts.

“It gets closer in terms of getting in-depth and thinking about the implications of social media monitoring,” she said.

To push more agencies to improve their policies, the Brennan Center is working with a member of Congress on federal legislation that would impose clear guidelines on how police departments that receive federal funding can surveil social media. Key features of such a bill would include:

- Restrictions on monitoring First Amendment-protected activities like protests, as well as monitoring people based on protected classes like race.

- Strict regulations for the use of undercover accounts, including warrant requirements.

- Limits on social media monitoring for general public safety reasons.

- Checks on how long police can keep information gathered via social media if it doesn’t relate to criminal activity.

Dave Maass, director of investigations at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital privacy advocacy organization, is particularly concerned with data retention.

“It’s not just a matter of (police) looking at it,” Maass said. “It’s a matter of them building profiles on people to target them for further investigation.”

The Austin Police Department’s social media policy sets clear restrictions and guidelines regarding the collection and retention of online data. (Graphic by Jimmy Cloutier)

Asked whether Phoenix police keep files or dossiers on activists, Williams wrote that the department follows a federal regulation that prohibits law enforcement agencies from collecting or maintaining intelligence on anyone’s “political, religious or social views, associations, or activities” unless there is reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

But Phoenix City Councilmember Carlos Garcia said he doesn’t believe that.

“I’ve ran into officers from other police departments who’ve said they’ve seen my file,” said Garcia, a former full-time community organizer. “The denial that they keep files on people or that they keep tabs on folks is really concerning. I think if there was legitimate — or they felt there was legitimate — reasons to keep these files, then that’s the information we want to hear.”

Activists on left and right feel targeted

Little is known about how Phoenix-area law enforcement prepared ahead of last summer’s protests. But police reports show glimpses of how officers monitored social media before there was suspicion of wrongdoing.

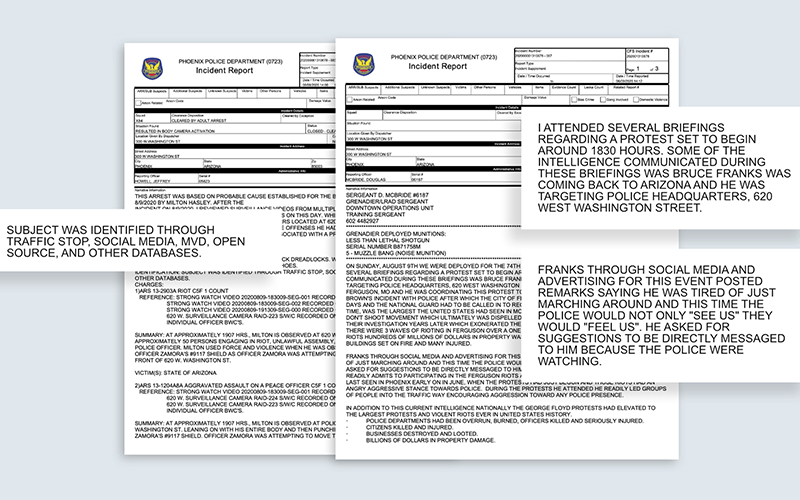

Iniko, the activist who’s seen police view his Instagram stories, was identified through “social media, MVD (Motor Vehicle Division), open source, and other databases,” according to his Aug. 9 arrest report. The report refers to him by his legal name, Milton Hasley.

Protesters Ricky Callan and Malyka Shively were also arrested that day. The police report shows Callan was identified using the same kind of intelligence as iniko, while Shively was identified using a “TLO database.” Terrorism liaison officers (TLOs) are police officers who monitor social media in partnership with the Arizona Counter Terrorism Information Center, one of dozens of fusion centers across the country that supports homeland security efforts.

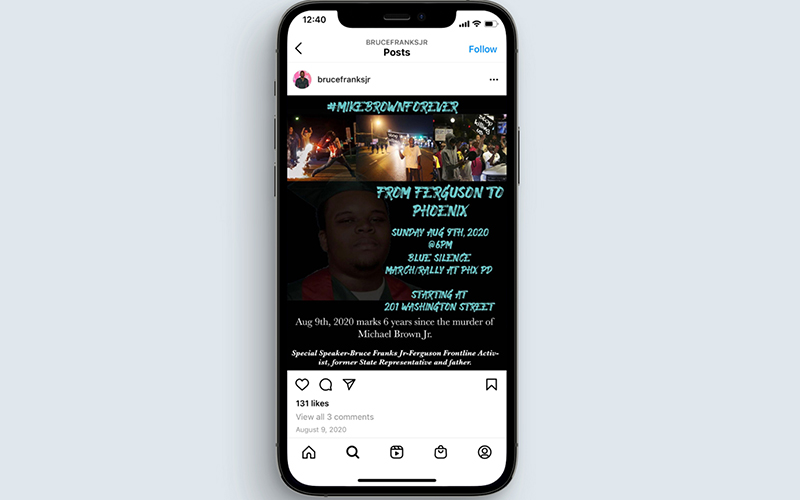

Bruce Franks Jr. used his social media to organize a “Blue Silence” march on the sixth anniversary of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri. (Graphic by Jimmy Cloutier)

Reports also show Phoenix police monitored the Instagram account of Bruce Franks Jr., an organizer and former Missouri state legislator with a large online following. Phoenix Police cataloged a flyer he posted online and flagged language in one of his Instagram videos as potentially threatening. In the video, he said police would “not only hear us, but feel us” — a line that was later referenced during a grand jury hearing, where Franks and other protesters were indicted on multiple felony charges, including rioting, resisting arrest and aggravated assault, which were later dropped.

Black Lives Matter protesters aren’t the only ones who say they’ve been surveilled.

Jennifer Harrison, a leader of the right-wing AZ Patriots group, said she knows local law enforcement uses online platforms to gather intelligence on protesters. The Southern Poverty Law Center has pegged Harrison’s organization as a “hate group” for its anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim and anti-LGBTQ comments.

Records show that police in Surprise monitored her accounts when she traveled to protest in California, and she suspects that Phoenix police surveil her, too.

“I know firsthand that they do use a bogus account that they create to monitor activists on all sides. They’re just doing their job, and I get that,” Harrison said. “But sometimes, you know, we feel like we’re being targets ourselves.”

Public records requests for communications within the Phoenix Police Department and ACTIC regarding protest surveillance went unanswered. ACTIC did not respond to an emailed list of questions either.

Lauri Stevens, a law enforcement strategist, said social media monitoring helps police avoid going into events blind. Stevens founded Social Media, the Internet and Law Enforcement (SMILE), an international conference that trains officers to use free, open-source software for investigations and community engagement. Phoenix police are frequent presenters at the annual conference, which will be held in Scottsdale later this year.

“They’ve got to start from somewhere,” Stevens said. “Personally, I’m cool with that. I wish they would do that because they’d catch a whole lot of people that way.”

Without clear policies, bias creeps in

But civil liberties experts say police interpret social media posts without specific and transparent parameters, allowing bias to creep in.

“What the police are doing is essentially saying critics of police culture — police violence — need to be surveilled,” said Jared Keenan, a senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona. “I think there’s just no demonstrable way to justify this sort of level of monitoring that’s going on here.”

Incident reports show that Phoenix police monitored the Instagram account of Bruce Franks Jr. ahead of an Aug. 9 rally, flagging language that was later referenced in grand jury testimony. (Graphic by Jimmy Cloutier)

Even former Assistant Phoenix Police Chief Kevin Robinson agreed.

“You can’t use that just because they don’t like the profession you happen to be in as a reason to start a criminal investigation,” said Robinson, who retired from the force in 2017 and is now a criminology instructor at Arizona State University.

Robinson pointed to controversial gang charges that were dropped after damning news reports by ABC15 revealed that police and prosecutors had trumped up the charges against protesters. They alleged that activists were members of an “ACAB” criminal street gang because they chanted the common anti-police slogan “All cops are bastards,” wore black clothing and carried umbrellas.

In the aftermath, eight citizens’ petitions were submitted to the Phoenix City Council, accusing police of engaging “in a widespread practice of politically motivated surveillance” and calling on Police Chief Jeri Williams to resign.

The lead prosecutor for the gang charges has been placed on administrative leave amid an ongoing investigation. The City Council has also hired 21CP Solutions, an external firm, to review the police department’s treatment of Black Lives Matter protesters.

Right-wing protests appeared to garner little police attention by comparison. Police made no arrests of armed Trump supporters protesting the election of President Joe Biden outside the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office in November.

City Councilmember Garcia said that’s a sign of unequal treatment.

“We saw some of the folks that were at the County Recorder’s Office eventually end up at the Capitol (riot),” Garcia said. “If you’re doing it to one side, I would expect you’re doing it to the other. But it didn’t seem to equate.”

At least five Arizonans were arrested for their involvement in the Jan. 6 riot. That includes Jacob Chansley, also known as Jake Angeli, who was a fixture at Phoenix protests before he became one of the most recognizable faces at the Capitol for his horned hat and fur cape.

The Phoenix Police Department did not respond to a question about whether Chansley was known to officers before the insurrection. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Justice did not respond to a question asking whether Phoenix police or other Arizona law enforcement agencies contributed intelligence to federal investigators.

Robinson said that during his tenure with Phoenix police, officers monitored the social media accounts of white nationalists “with a great deal of regularity” and often created undercover accounts to infiltrate extremist groups.

But that doesn’t reassure Chad Marlow, senior advocacy and policy counsel at the ACLU.

“If you have someone who is Black or Muslim and is politically active on the far left or far right, they are probably going to be surveilled somewhat differently because you are working in different layers of bias,” he said.

Pushing for police accountability

To mitigate bias, one state lawmaker is pushing for greater police accountability and regulation of online surveillance.

State Sen. Juan Mendez, D-Tempe, is the sponsor of Senate Bill 1583, which would increase transparency for how police monitor social media. It’s Mendez’s version of the Community Control Over Police Surveillance law, a bill drafted by the ACLU. About 20 jurisdictions nationwide have adopted CCOPS laws, such as New York City, San Francisco and Seattle, but none are in Arizona.

Mendez’s bill is effectively dead in the Republican-controlled legislature, where two GOP lawmakers proposed bills that would create or increase felonies for protesters who engage in a “riot” or block a public thoroughfare — two common charges brought against protesters last year.

A protester approaches a line of police officers in downtown Phoenix on May 31, 2020, in one of several days of protests over the deaths of black men in police custody around the U.S. A statewide curfew was imposed that night. (Photo by Blake Benard/Special to Cronkite News)

Though his surveillance bill is unlikely to pass, Mendez said he hopes to raise awareness of an issue that’s not going away.

“If it’s supposed to be keeping us safe, then we should know (more about it),” Mendez said of social media monitoring. “What’s the harm in letting us know what’s going on or what information is being collected and how it’s being used?”

Robinson said the law would be a “win-win for both sides,” even if law enforcement is reluctant.

“Initially, people will balk at it: ‘We’ll never be able to convict people now.’ But they said the same thing when the Miranda rights came down,” he said. “There’s nothing wrong with reporting to the people who write the checks.”

Without laws that better regulate social media policies, civil liberties advocates say police surveillance will continue to erode free speech. And many protesters worry that the threat of police surveillance will suppress racial justice activists.

“I hope this doesn’t discourage the other general public to not come out because they see what’s happening and they’re scared it’s going to happen to them,” said Black Lives Matter protester Brandon Valentin. “This is your First Amendment right, and the cops are making you scared to do it.”

This article was produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard.