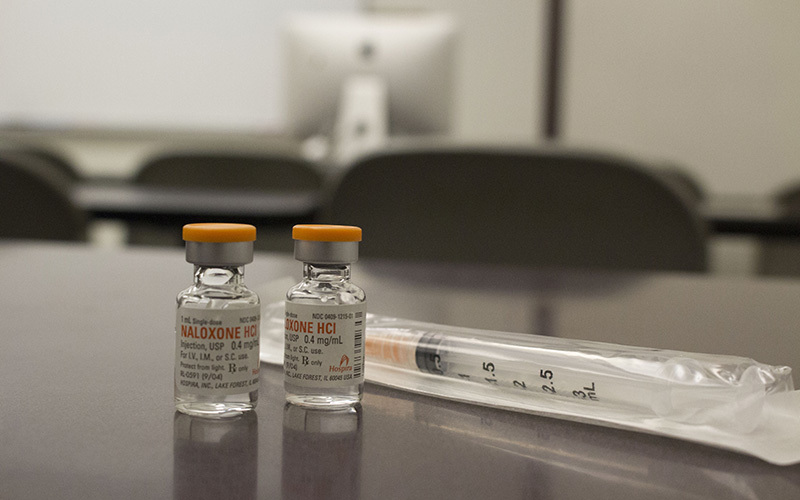

Amid record overdose deaths in the U.S., policymakers are proposing measures to expand treatment, direct more funding to the problem and reduce the chance of overdose with expanded access to the opioid reversal medication naloxone. (File photo by Faith Miller/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – The United States just recorded its highest number of overdose deaths ever seen in a 12-month period – a grim milestone that highlights the weight of the coronavirus pandemic on the prolonged opioid epidemic, as well as the need for more solutions.

At the federal and state level, policymakers are proposing increased funding for substance use prevention and more access to medication-assisted treatment. Meantime, advocates on the ground are calling for more investment in overdose prevention strategies.

President Joe Biden is requesting $10.7 billion from Congress to support medication-assisted treatment, research and additional behavioral health providers, with an emphasis on assisting Native Americans, older people and rural populations.

In March, Biden signed into law a measure appropriating nearly $4 billion to expand access to behavioral health services, enhance efforts to prevent overdose and advance racial equity in the approach to drug policy. Biden has also said that people should not be incarcerated for drug use but offered treatment instead.

These moves come as preliminary statistics indicate “2020 will be the worst year for opioid overdoses that we’ve ever had,” said Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management at Harvard University.

“The COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. isn’t just about COVID-19, it’s about managing all of the spillover effects, including the effects it has had on people with addiction and substance use disorder,” Barnett said in a post on the Harvard School of Public Health website.

“It unfortunately looks like we have lost a lot of progress we had made on opioid overdoses in recent years because of the pandemic.”

Here’s a look at some proposals aimed at addressing the setbacks:

Fighting fentanyl

Synthetic opioids, particularly fentanyl, are largely to blame for spikes in overdose deaths, so several proposals target this pain medication, which is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and potentially deadly in even tiny amounts. Fentanyl often is laced into other drugs, and users may not know.

Measures pending in Congress would permanently criminalize fentanyl analog drugs as Schedule I controlled substances, alongside heroin, LSD and others, meaning they have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use. These analog drugs are manufactured in a lab to produce the same effects as natural opioids.

In 2018, the Drug Enforcement Administration temporarily scheduled fentanyl analogues as controlled substances, and last year Congress extended that. But the measure expires May 6; these proposals would make the change permanent.

The American Civil Liberties Union and other advocacy groups have urged leaders to reject the permanent classification, saying the move would reinforce an “enforcement-first response to a public health challenge” and worsen racial disparities in mass incarceration.

Beyond those measures, other proposals involve the regulation and distribution of fentanyl test strips, which advocates say can help reduce overdose deaths.

The strips identify the presence of fentanyl in injectable drugs, powders and pills. Each single-use strip is dipped in water containing drug residue, and a minute later, red lines appear – one line means the liquid contains fentanyl and two mean it does not.

On April 7, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration announced that federal money can be used to purchase rapid fentanyl test strips. The change applies to all federal grant programs as long as the purchase of the strips is consistent with the purpose of the program.

“The increase in drug overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids, such as illicitly made fentanyl, is a public health crisis that requires immediate action and novel strategies,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky said in announcing the change. “State and local programs now have another tool to add to their on-the-ground efforts toward reducing and preventing overdoses, in particular fentanyl-related overdose deaths.”

Some state legislatures have acted to legalize fentanyl test strips, which often are banned under drug paraphernalia laws, according to the Minnesota-based Network for Public Health Law.

A measure pending in the Arizona Legislature, which concludes its session April 30, would legalize the use of the test strips. The effort was led by state Sen. Christine Marsh, D-Phoenix, whose 25-year-old son, Landon, died last May after taking fentanyl-laced drugs.

“I don’t know if a fentanyl testing strip might have saved my son’s life, but I do know that we have a chance to save other lives and other families from experiencing the soul-crushing grief that I know too well,” Marsh wrote in a January column in the Arizona Mirror.

Needle exchanges

Programs to distribute syringes so that users don’t use dirty needles and spread infection are hardly new, but 19 states still have not authorized syringe programs, according to a March report by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

For several years now, proposals to legalize needle exchange programs have died in the Arizona Legislature. Another bill was awaiting final approval in the House as the session neared an end.

The programs allow injection drug users to exchange dirty needles for clean ones, preventing the spread of infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C. The CDC reports that 44 states, including Arizona, are experiencing, or at risk of, significant increases in hepatitis infections or HIV outbreaks due to injection drug use.

The CDC points to research that shows new users of syringe services programs are five times more likely to enter drug treatment and three times more likely to stop using drugs than those who don’t use the programs.

The programs can also decrease overdose deaths by training people who inject drugs on how to recognize, respond to, and prevent a drug overdose by using naloxone, a medication used to reverse overdose.

Biden has said he wants to provide more funding support for such programs and lift barriers limiting access.

More Narcan to more people

Access to medication that can stop an opioid overdose increased in the 2000s as the epidemic worsened, and it’s now commonly used by police, paramedics and emergency room doctors.

Amid increasing overdoses this past year, a push is on in some states to get the medication into the hands of more people.

Naloxone, often called by the brand name Narcan, is a temporary treatment that can reverse and block the effects of opioids, including heroin, morphine and oxycodone. It can be injected in a muscle, vein or under the skin, or sprayed into the nose.

Researchers at Pew say all U.S. states have enacted at least one law expanding access to naloxone, but not all allow lay people easy access to the medication. The U.S. surgeon general and experts at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration are among those emphasizing the importance of access to naloxone in reducing overdoses.

Proposals include everything from distributing the medication to people when they are released from prison or drug treatment to enacting laws that eliminate the need for a doctor to prescribe naloxone. (In Arizona, the state health department has a standing order allowing anyone to purchase naloxone from any pharmacy in the state without a prescription.)

New York last year extended legal protections to restaurants, bars, malls, beauty parlors, theaters, hotels and retail establishments so that they can possess and use naloxone without fear of penalty.

“Opioid-related overdose deaths frequently occur in public spaces. Yet, many of these public spaces have restricted the administration of naloxone on their premises due to the concern that they would not be covered” under “Good Samaritan” laws, stated a news release from Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office.

Some law enforcement agencies, including the Pinal County Sheriff’s Office in Florence, are providing Narcan to the public for free. The department announced the decision after nearly 600 people in the county died of a suspected opioid overdose from early April 2020 through late November.

“If you or a loved one uses opioids, Narcan is now available … during normal business hours, no questions asked,” the department said.

More medication-assisted treatment

Earlier this year, a group of U.S. senators introduced a bill that would increase funding to fight the opioid epidemic through education, treatment and prevention.

The measure making its way through Congress would prohibit states from requiring prior authorization for medication-assisted treatment under Medicaid and permanently allow providers to prescribe such treatment without a prior in-person visit.

The bill would also allow physicians to treat an unlimited number of patients with buprenorphine, a medication that treats opioid dependence.

In the past, providers wanting to prescribe buprenorphine had to first undergo training, notify the federal government and receive a practitioner waiver. That policy was loosened recently to allow prescriptions for up to 30 patients without the training requirement. The measure pending in Congress would go even further.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented challenges, and we are now seeing another heartbreaking surge in overdose deaths. That is why we must redouble our efforts to combat addiction and help those who are suffering during this crisis,” Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, said in announcing the bill.

“In the new Congress, we have a unique opportunity to work together in a bipartisan way,” Portman said, “and I believe that (this bill) can help us make a real difference in combating this epidemic.”

Editor’s Note: If you or someone you know needs help with a substance use problem, SAMHSA’s National Helpline – 1-800-662-HELP (4357) – is a confidential and free 24/7 information service, in English and Spanish. SAMHSA’s Buprenorphine Practitioner Locator can help identify a qualified practitioner who can prescribe buprenorphine for opioid-use treatment.