TUCSON – “Getting lost is the best part of trail running,” Marlinda Bedonie said with a chuckle as we shielded our eyes from the morning sun, searching for our cars.

We spoke on a recent morning while trekking through Tucson Mountain Park on a mostly flat, single-track loop trail. Dipping in and out of washes and brushing against the creosote along the trail, the Tohono O’odham and Navajo mother and I chatted – out of breath – as we shared our running journeys and spoke about our families.

When we came to what we thought was the end of our loop, we realized that although we’d learned a lot about what we share in common, neither of us had any idea where our cars were.

Sometimes, getting lost can be part of finding yourself. In the past four years, Bedonie, 41, has found a passion for running and representing her culture in the sport. She often is featured on the Native Women Running Instagram page highlighting her half-marathons, 10Ks and other races.

Even when she’s jogging Arizona trails solo, she’s far from alone.

In 2018, Verna Volker, who’s Navajo, launched Native Women Running on Instagram. Just more than three years later, her account has more than 19,000 followers and she’s an ambassador for the running shoe company Hoka One.

Volker had started running in 2009 and soon realized something was missing in the community – representation by non-white runners.

“As I got more into running, I realized how little diversity there was,” she said. “I remember going through Instagram and I saw the same type of runner: the cute, white, blonde, fit (woman) who just ran Boston, and I just felt like I couldn’t relate.”

The Boston Marathon may be considered “the holy grail for distance runners” but for Volker, running isn’t about being invited to legacy races, it’s about creating a space for people like her.

Native Women Running restores an Indigenous perspective to running and gives Indigenous women a platform to showcase their cultures and their passion for this ancient celebration of life.

“Native people once had messengers who would run to the next tribe over to carry a message, so it’s kind of ingrained in Native people to run,” she said. “There’s a physical part of (running), but I think that, a lot of times, running was used for prayer runs and still today, it’s a spiritual exercise for Native people.”

Running also represents a spiritual connection to the land for Volker.

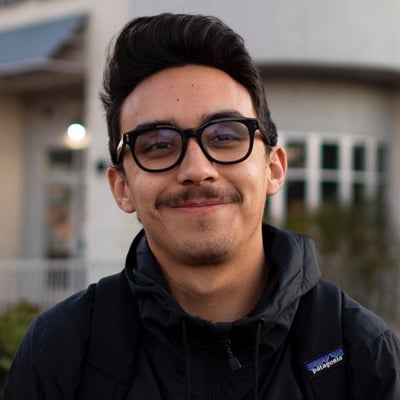

Marlinda Bedonie hopes to inspire more Native women across the country to enter her sport, and raise awareness for important social justice issues facing her community. (Photo by Ike Everard/Cronkite News)

“I always encourage my women to run the land wherever they are,” she said. “Some of us are not on the reservation, we’re in the middle of Chicago or Minneapolis, and I just encourage them to run where you are, because running it acknowledges who you are as a people.”

My run with Bedonie reflected that spiritual aspect. During our 4.5-mile trek through Tucson Mountain Park, she stopped occasionally to tell me about her daughters, her experiences running and her connection to the land we were on.

When she was a girl, her aunt used to bring her out early in the mornings to this area to harvest the fruit of the saguaro (or bahidaj, as it’s known by the Tohono O’odham) that stood tall and proud all around us.

On the day we got lost, she looked at ease, comfortable, and said later that she knew her late aunt was there watching over her.

“Running for us is celebrating life,” she said. “We’re not just running for us, we’re running for our people, we’re running for those who can’t, we’re running for prayer.”

Dirk Whitebreast, founder of Native-owned Red Earth Running Co., which organizes runs, sells clothing for Indigenous runners and uses proceeds to benefit Indigenous causes, said he sees hope for Native people in such events as the upcoming virtual Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women National Day of Awareness Run, hosted by Native Women Running.

Whitebreast said he and his company, which coordinated the virtual run with Native Women Running, want to let groups like Native Women Running take a more active role in these pushes for awareness and action.

“We decided to take a step back on this issue and let others lead,” he said. “Native Women Running is a really sound platform. Verna does a really good job of bringing attention to the issue.”

And the issue is huge. The Urban Indian Health Institute found that in 2016, the most recent year data are available, 5,712 Indigenous women were reported as missing or murdered in 71 U.S. cities.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, two weeks after being sworn in, created a Missing and Murdered Unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs dedicated to finding justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women, highlighting the urgency of this pandemic of violence against Native women, girls and Two Spirit individuals.

Native women are up to 10 times more likely to be murdered than the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, and murder is the third leading cause of death for Native American people ages 10 to 24.

“I really have a heart for that,” Volker said, “because through this work that I’m doing and these virtual runs, I have had women who messaged me their stories and real incidents where they’ve lost their mother or they have a niece who was never found. What we’re supporting and bringing allies to help us raise awareness around this is really important to me.”

For Bedonie, running in prayer for the protection of her people and family is important as well.

“I have family who I keep in prayer” while running, she said. “And everybody is going through a lot right now during this pandemic. We’re losing our family and we’re losing our friends. We have to say those prayers, we need them to be protected.”

And as she and I ran through washes and jumped over rocks, a silence fell over us, leaving the crunch of our shoes on gravel as the only sound. When the silence ended and she talked about her college-aged daughter’s first half-marathon, it became clear that she was thinking about her family even as we were just a bit lost in the Tucson Mountains. Her children were at the front of her mind, her prayer in motion.

Volker’s experience running is similar.

“I am so thankful that running has found me,” she said. “There are times when I run and I’m just bawling. When I started doing ultra races, I would write family members’ names on my shoe to give me that motivation of running in honor of my brother or my sister or running in honor of my dad.”

She said that her running helps her deal with loss, and it has become a healing ritual for her and countless others.

“In Native Women Running, I have women who run for their husbands or their sons and it’s in that way that we relate so much,” she said. “And I think that’s why people gravitate toward Native Women Running.”

But this commonality alone isn’t what makes Native Women Running so special – it’s also the safe space and community that she has built.

When Benodie was featured in an Instagram ad for Dick’s Sporting Goods, she told Volker that she likely wouldn’t have gotten that chance without Native Women Running.

Volker was humbled and joyful.

“She messaged me and she said, ‘Verna, if it wasn’t for you, I would have never gotten that opportunity,’ and that almost makes me cry because that’s what I do,” Volker said. “It brings me much joy to do that, and I’m thankful for how much these women inspire me, too.”