PHOENIX – Hamza Abdullah played seven seasons as an NFL safety, including three with the Arizona Cardinals, making his mark in the league primarily on special teams during a career that lasted twice as long as the average NFL player’s.

But Abdullah’s quest for a starting job – well, it was almost Sisyphean.

Just as Sisyphus was sentenced to push a boulder to the top of a hill in Greek mythology only to have it roll back down, where he would start all over again, every time Abdullah seemed about to reach the top of his team’s depth chart, he came up against an obstacle that was seemingly his alone to face.

“In every training camp, I feel like I would either be a starter or vying for a starting position,” Abdullah said. “Then Ramadan would come, and from the team’s perspective, they’re looking at it like, ‘Well, we don’t want to overburden Hamza.’”

Abdullah is one of 3.5 million American Muslims, 80% of whom observe an intermittent fast during the lunar-calendar month of Ramadan, which runs from April 12 to May 12 this year. From sunrise to sunset, as they strive to get closer to God, they renounce all food and drink and attempt to curb other vices. Traditionally, they break their fast with a substantial nighttime meal called iftar, then eat a smaller morning meal, sahur, before the sun rises.

Abdullah said that he absolutely doesn’t blame Ramadan for his inability to land a starting job because, despite facing the same challenges, his younger brother Husain was able to start for the Minnesota Vikings.

But the shift in eating and sleeping patterns represents an undeniable, unique obstacle for Arizona’s Muslim athletes, who operate at an apparent deficit compared to their full-bellied, hydrated peers. And they must adjust their training habits accordingly – especially when Ramadan falls during Arizona’s 115-degree summers. (The Islamic month moves back about 10 days each year in relation to the Gregorian calendar.)

“I wouldn’t really think about it until I came to a timeout,” said Hamza Shami, who played basketball at Mountain Ridge High School and Glendale Community College. “Like, Coach will call a timeout and everybody’s drinking water, and I’m just standing there.”

Fasting: challenge or opportunity?

Dr. Matt Anastasi, a sports medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, identifies three key considerations for fasting athletes: hydration, sleep and nutrition. In Arizona, hydration takes on particular importance.

“Our temperatures are going to be hotter than most places in the States,” Anastasi said, “and we do have an abundance of daylight – we’re looking at roughly 12 hours of inability to eat, which is a long time for an athlete.”

If they don’t properly attend to these factors, Muslim athletes can struggle, because poor nutrition and a disrupted sleep schedule is not a recipe for athletic success. According to a 2011 study of Singaporean martial artists in the Asian Journal of Sports Medicine, fasting athletes may have diminished rapid-response cognitive function, particularly later in the day.

It isn’t all in their heads, either.

Usama Shami, preseident of the Islamic Center of Phoenix, said the Phoenix mosque draws up to 800 worshipers every Friday, considered a holy day. (Photo by Joey Carrera/ Cronkite News)

A 2007 study of Algerian soccer players in the British Journal of Sports Medicine demonstrated a corresponding decline in physical performance when fasting is paired with lower-quality training.

“You can’t really give everything like your teammates are,” said Ammar Ćeman, who played basketball at North Pointe Prep. “And you’ve got to monitor yourself to a certain point, because if you go above that point you could collapse, obviously, from dehydration.”

Despite these considerable obstacles, however, many Muslim athletes choose not to view Ramadan as a negative. Far from it. In the 1990s, Houston Rockets star Hakeem Olajuwon famously said he “felt stronger and more energetic” while fasting.

And amid the dehydration and sleep deprivation, many Muslims say they derive considerable mental or spiritual benefits from fasting. Abdullah – who cites Olajuwon, former Denver Nuggets guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf and Heisman Trophy winning running back Rashaan Salaam as inspirations growing up – said his focus became more intense during fasting, to say nothing of the “feeling unlike any other” of his connection to God.

Ćeman, too, has experienced benefits.

“When I’m fasting, I feel like I think clearer,” Ćeman said. “I feel like there’s a lot less to worry about … it just paints a clearer image, and it’s probably one of the most peaceful things for me to do.”

For Aadem Isai, a sophomore basketball player at Valley Vista High School (where his father Ben is head coach and Shami is an assistant), the short-term physical limitations of fasting provide a long-term advantage.

“As a player, I am required to play a lot and to run a lot without water for certain amounts of time,” he said. “And with that, just practicing that continuously for a month straight, it can get me used to that factor.”

Support systems

In Arizona, where just 1% of the population is Muslim, Ramadan could easily become an isolating experience without support from teammates and coaches for fasting athletes. Not everyone has the chance, as Ćeman did when he was young, to fast while attending an Islamic private school, where everyone is participating.

In high school, however, he said his coaches were very understanding and either adapted or made portions of his training optional over the summer.

“They were very communicative,” Ćeman said, “and they wanted to make sure to let me know I’m not in it alone.”

During one week-long summer league tournament at North Pointe, Ćeman was so desperate for some semblance of hydration that he brought two water bottles to games: one full and one empty. One contained water to rinse his mouth with, and the other one was to spit the water into because he could not swallow it.

“That was the only way I would keep my mouth somewhat hydrated – not hydrated, but preserved, in a sense, for me to keep going,” he said. “That was the only thing that I was doing to help me maintain my level of play and consistency.”

Shami said that as a kid, he didn’t think actively about his faith very much while playing sports. One particularly brutal summer day at Mountain Pointe, though, he had to contend with three games in a five-hour span while fasting, and he forced himself to take a bigger-picture view.

“There’s millions of people around the world who go through this every day,” he said. “I mean, I’m just doing it until sundown, and it’s by choice. There’s millions of people who have to do this in their daily life.”

One of the biggest obstacles for these athletes is timing. The further they get from sunrise, the more likely they are to get fatigued if they haven’t prepared properly.

“The better off they are from a hydration perspective, the more full they will perceive to be,” Anastasi said. “And that will also help them kind of avoid the (potential) afternoon or mid-afternoon crash.”

Shami said the hardest part of fasting was finishing a big athletic event long before the iftar: “You’re already dead tired, and you’re hungry and thirsty, and you have that extra three or four hours where you’re just staring at the clock.”

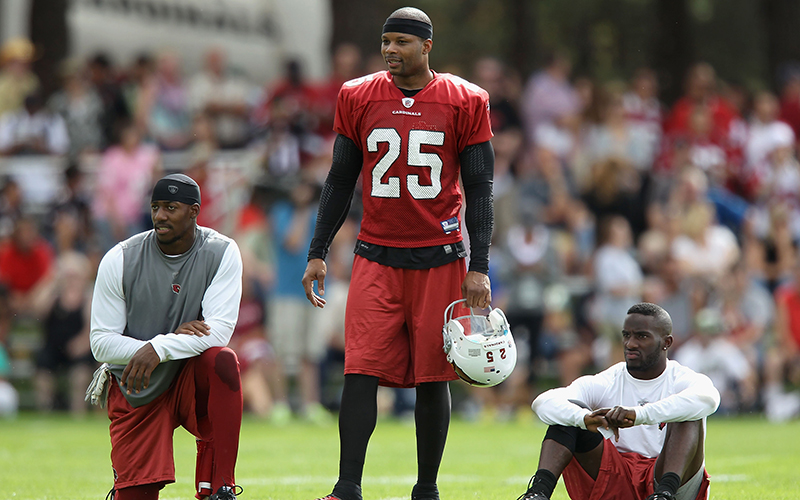

Abdullah (left) became good friends with Michael Adams (right) when both played on the Cardinals. Adams would eventually join Abdullah for suhur, the meal early in the morning before fasting begins. (Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images)

Haris Hajric, a friend of Ćeman’s and lifelong basketball player, remembers one game in an indoor recreation league where his timing was much more fortuitous. With his team already lacking players, he was concerned about his endurance. But early in the game, he felt great.

“I actually found that I felt much lighter,” he said, “and that game, I ran more than any of the other games.”

Then, before he could get too exhausted, he got a reprieve at halftime, when the sun set. Hajric was then able to end his fast with “a much-needed water break” and proceed as normal through the second half.

Hajric said having the support of his peers helps him through Ramadan. Abdullah found the same to be true when he joined the Cardinals.

“They were the first team to ask me, ‘What can we do to help you?’” he said.

He hadn’t found his previous teams nearly as sympathetic. For instance, in Denver, when he sustained a hip flexor injury during Ramadan, he said Broncos staff insisted it was because he was fasting.

“The very next week, one of our tight ends got the exact same injury,” Abdullah said. “And so I went to them, I said, ‘Is it because he’s fasting?’

“They didn’t like that too much,” he said, pausing to chuckle at the memory. “I ended up getting cut.”

But in Arizona, even as Abdullah struggled with the altitude at training camp in Flagstaff, he had the support of Ken Whisenhunt, who was the coach at the time, and Rod Graves, who was the team’s general manager back then. Most caring of all was his teammate and roommate, Michael Adams, whom he affectionately calls “Money Mike.”

“Hamza, I smelled you cooking before practice,” Adams would tell him. “One day I’m going to come in there, and I’m going to join you for breakfast.”

So Adams got in the habit of joining Abdullah for his sahur: waffles, eggs, Morningstar Farms sausages, fruit and coconut water. The imitation sausages in particular were a hit, and Adams said he would fast from pork, as long as he could keep getting the sausages. The two bonded over their shared pre-dawn breakfasts, and have kept in touch since.

“Since then, every year he texts me, he says, ‘OK, Hamza, it’s Ramadan, I’m gonna give this up,’” Abdullah said. “And so he gives up different things. …

“I’m just so appreciative of him, specifically, and other teammates like him who have really been there to support me.”

Connecting through basketball

One new group in Arizona aims to provide a built-in community for Muslim athletes of various ages and skill levels: the Muslim Basketball Association of Arizona, or @muslimhoopersaz. Initially led by Shami and Ćeman, both currently students at Arizona State, the group has hosted weekend pickup games, primarily at Inspire Courts in Gilbert, for about two months.

Both founders are well-connected in Arizona Islam. Shami is involved with the Islamic Community Center of Phoenix, where his father Usama is president. Ćeman is president of the youth board at the Islamic Center of North Phoenix, and his father Sabahudin is a leader both at that mosque and in the broader Bosniak Muslim community.

Shami and Ćeman had been playing basketball for months together during quarantine when they got the idea for the group. Shami took inspiration from Arizonan Assyrian communities who gather to play basketball, as well as Muslim groups in larger cities like Chicago.

“My only intention is to bring the community closer through basketball,” he said, “because one thing about basketball: Even if somebody sucks, they will go to the gym to play.”

Ćeman said basketball provides an appealing alternative to traditional ways of uniting discrete Muslim communities: guest speakers, visits to each other’s mosques and so on.

“I’m not knocking anything like that – that’s a great way for all of us to connect and learn something – but this is a different approach, a more relaxed approach,” he said.

The games have boasted great numbers so far – on one weekend in March, the group drew 80 players – and Ćeman said he’s starting to get to know more participants every week as he aims to “tie our communities together.”

Now the group hopes to keep its momentum through Ramadan, a shared experience, largely unseen by the secular world, that puts a physical strain on all its participants.

“It’ll kind of be nice to see how that transitions into fasting … if so many people are still going to show up,” Hajric said.

Isai embraces the conditioning challenges of Ramadan, and he’s looking forward to the communal environment Shami’s group will provide during his fast.

“It’s always good to be around your Muslim brothers,” he said. “I think with me going there through Ramadan, it’ll help me get closer to other people and maybe build lifelong relationships with them.”