Editor’s Note: This story is part of an ongoing project to highlight Black athletes who have broken barriers and made lasting contributions to Arizona sports.

PHOENIX – Jackie Robinson made his major league debut on this day in 1947, shattering the color barrier of Major League Baseball. Every 15th of April, Robinson is remembered and honored for opening the door for other Black athletes to play America’s pastime at the highest level.

Robinson’s courage and decency touched millions, including Joe Black, Robinson’s former roommate, who created his own legacy on and off the diamond, in Arizona and elsewhere.

Black, a 6-foot-2 right-hander from New Jersey, joined Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1951 after spending parts of the previous eight years with the Baltimore Elite Giants, a Negro League team.

Black made his MLB debut in 1952 and became the first African American pitcher to win a World Series game the same year. He also won the 1952 National League Rookie of the Year award, at age 28.

Black was more than just a ballplayer – he spent many years in Phoenix working for Greyhound and the Arizona Diamondbacks, as well as giving through charity work around the Valley.

Jerry Reinsdorf, the owner of the Chicago White Sox and Chicago Bulls, was introduced to Black in the mid-1990s. Black soon learned that Reinsdorf is from Brooklyn, where Black once pitched.

“Joe is bigger than life, bigger than life, both literally and figuratively,” Reinsdorf said. “You know, when he played, he weighed around 200 pounds. After playing, I think he admitted for 350. So I think he was probably 375 or more. So literally, he was bigger than life.”

When Black showed up at the Dodgers’ spring training camp in Vero Beach, Florida, in 1952, he was assigned to room with Robinson. Black wrote in his autobiography, “Ain’t Nobody Better Than You,” that Robinson taught him the mental changes Black baseball players had to make to survive in the majors.

“Jackie’s like, ‘You know how to fight?’ My dad’s like, ‘Oh yeah!’ He goes, ‘Well we’re not going to do that. Because if we do that, we can’t open the door for the other people that are coming through,’” Black’s daughter, Martha Jo, told Bally Sports Arizona’s Jody Jackson in 2020.

“We have to do this for others. We have to know this is not just about us, it’s about everybody.”

Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen relied on Black as a relief pitcher in the second half of the 1952 season, due to Don Newcombe’s military service and the injuries of other pitchers.

By the end of the regular season, Black appeared in 56 games, winning 15 and recording 15 saves. He compiled a 2.15 earned run average in 142 innings, and Brooklyn was in the World Series again.

Dressen still had a depleted pitching staff, so Black started Game 1, which he won. He started Game 4 as well, but lost.

Black never pitched quite like he did his rookie season, so in June 1955, he was traded to the Cincinnati Redlegs. At the time, there were no player agents or contract negotiations. He learned about the trade while riding to work.

Somebody was kind to drive him to work because he took the train to the ballpark,” Martha Jo said. “And he heard on the radio that he was traded.”

Peter O’Malley, the former owner and president of the Los Angeles Dodgers, first met Black at spring training at Vero Beach, and they remained friends long after that. O’Malley said Black was competitive on the field.

“He looked like he enjoyed his work. I thought he enjoyed the challenge of trying to get the batter out, strike him out, whatever,” O’Malley said. “That competitiveness drove him. He was prepared. He practiced. He trained. He did not consider it to be a hobby. He knew it was a job.

“But his focus was ‘I can’t let my teammates down. I’ve got to be prepared. I’ve got to be in shape. I’ve got to do my homework. I’ve got to know how to pitch to this batter. Because I don’t want to let this team or the fans down,’ and he was very loyal to his teammates and his fans. And that’s why he was so popular.”

Black’s final MLB appearance came on Sept. 11, 1957, with the Washington Senators.

Following his baseball career, Black returned to his hometown of Plainfield, New Jersey, where he taught physical education and coached junior and senior high school baseball. Black began working for Greyhound in Chicago in 1963; by 1967, he was vice president of special markets for the bus line, moving to Phoenix in 1971 when Greyhound relocated its headquarters.

In 1989, new MLB commissioner Bart Giamatti hired Black to talk with players about their futures and how to handle the money they earned through their contracts, which had steadily increased since the mid-1950s.

Black saw some players struggle with their finances after retiring from baseball. Because of this, he, along with Joe Garagiola, Ralph Branca and other former players, founded the Baseball Assistance Team to help former players and others in MLB with expenses they couldn’t afford.

After Phoenix was awarded a new franchise in 1995, Black became the Diamondbacks’ community affairs representative. A mainstay at the Diamondbacks’ batting practices and in the press box, Black traveled to games across the country with the team.

He also was heavily involved in such organizations as Big Brothers Big Sisters, the Salvation Army, the National Minority Junior Golf Scholarship Association and Kiwanis International.

He was also a well-known public speaker and writer. Black contributed a national column, “By the Way,” from 1969 to 1985, which was read in more than 40 Black newspapers and magazines, including Ebony and Jet. He also recorded his columns for broadcast on over 50 radio stations that appealed to Black listeners.

In these columns, Black expressed his support for the civil rights movement and the struggle to end racism. However, he put the responsibility on the Black community to end social revolution and take advantage of new opportunities that existed because of the work of activists and civil-rights leaders.

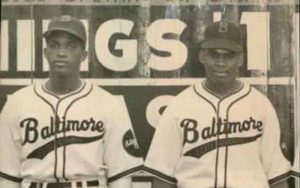

Joe Black, left, joined the Baltimore Elite Giants, a Negro League team, in 1943. Black left to serve with the Army Medical Corps during World War II and rejoined the team in April 1946. He played for them through the 1950 season. (Photo courtesy of Martha Jo Black)

Black, who graduated from Morgan State University in 1950, stressed education and intellectual power as one solution to help Black people thrive and escape the problems that settled into low-income communities.

“If they learn, they’ll have a better chance to earn. Our youngsters must be encouraged in their school work. They must be made to feel that there is hope and their dreams can come true,” Black wrote in his “By the Way” column in an April 1987 issue of Ebony.

Black also stressed the importance of education in his own home. One person who knows that better than anyone is Black’s daughter, Martha Jo, who now lives in Chicago and works for the White Sox. She was raised by her father, who gained sole custody when Martha Jo was 5.

“I do know his biggest thing for me, being a single father since my parents got a divorce and he had sole custody of me when I was 5 years old, was all about education,” she said. “My dad always came to the school and asked the principals, ‘If you have a problem with my daughter, you call me. Here’s my card. If I’m out of town, my secretary will find me and I will call you.’”

Black wasn’t in the spotlight much. O’Malley said he was a modest man and would turn down nine out of 10 offers to be honored. But in 2002, the Arizona Fall League honored Black by naming the Fall League MVP trophy after him.

“My brother and I went out there for that,” Martha Jo said. “And I was very honored about that. I definitely think that is why (they honored him) because at the time, there were, I think, a few more African American players in the game, which they are not now. So hopefully, you know, besides that there’s Jackie Robinson and there’s my dad. There’s Don Newcombe. There’s Roy Campanella. And if they can do it, so can other young people.”

O’Malley said Black – who was 78 when he died May 17, 2002 – had a profound impact on the lives of those who knew him.

“He was the best. By that, I mean, he was smart. He had great communication skills, was engaging,” O’Malley said. “He was the kind of guy that I enjoyed looking forward to seeing. He was the kind of guy that I enjoyed being with in his company. I enjoyed hearing his experience, what he was doing, what the challenges were in his work. And it was not just baseball talk or how the team is doing. It was just as much if not more, how is Joe doing? But he was unique. I consider him a very close friend.”

Reinsdorf said Black made his life more pleasant – they used to have lunch together every couple of weeks.

“Just sit and talk for a couple hours. And, of course, you know, my heroes, the Brooklyn Dodgers and we used to talk a lot, a lot about the guys that he played with,” Reinsdorf said. “Some of them like I came to know in later life, many of them I didn’t. And I heard stories about the Dodgers and about Jackie Robinson, Carl Erskine and the other players, Pee Wee Reese. I think he really had great stories, great stories about them.”

Reinsdorf said Black always wanted to help. O’Malley described Black as a giver. Martha Jo Black saw that first hand.

“It wasn’t because he wanted anything from you. But he’s like, ‘I want to uplift you and help,’” she said.

The Baseball Assistance Team continues its mission today, helping members of the baseball family with any financial, medical or psychological assistance. Black’s friends also continue to promote education in their organizations. The Dodgers run multiple educational programs every year, such as LA Reads, which helps students to stay on track with reading at home. The Dodgers Foundation also awards education grants and uses its platform to create curriculum that gets students excited about reading. The White Sox sponsor a Good Grades program and run an antibullying assembly to show students.

Black’s influence on baseball and the communities he was a part of are clear. After Black’s death, Morgan State created the Joe Black Endowed Scholarship for Aspiring Teachers. Every year since 2010, the Washington Nationals give the Joe Black Award to the person or group who continually promotes baseball in Washington, D.C.’s inner city. The Diamondbacks named a room after Black at Chase Field. O’Malley said Black deserves more recognition than he was given during his life.

“But Joe’s life, from beginning to end, should not be overlooked or just filed away,” he said. “I wish Joe had gotten more recognition in his time.”

When Martha Jo was 8 or 9, her father took her to the Phoenix Opera. She wore a dress, and her father, a suit, while other audience members had on cowboy boots and jeans. Black said he would take Martha Jo to the New York Opera, so she could see how it really is. He used these times to teach his daughter that people are different, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

“He wanted me to be broad so I could not judge people,” Martha Jo said. “And I think that was the biggest thing like playing in the Negro Leagues and traveling, and how he traveled and playing in Venezuela and Cuba. You see how people are, you see how people are treating each other, so you’re like, ‘Oh, we’re all the same.’ And when you know that, you don’t treat anybody any differently.”