PHOENIX – Maria Brown-Spence lost two people to cancer in six years – her grandmother in 2012, her significant other in 2018. Grief-stricken, she tried to get help but found few mental health resources for people who look like her.

If it wasn’t the cost of the copay, it was the cultural distance between Brown-Spence and the therapist in front of her. If their lived experiences weren’t shared, it felt to her they were miles apart.

“A lot of the curriculum was from the white perspective,” she said. “There wasn’t my voice from a social justice or racial equity lens that taught it’s beyond the physical being we’ve lost … it’s understanding that generational trauma has impacted us.”

Because she couldn’t find an organization that met her needs, she started her own. Brown-Spence, a self-described Afro-Latina, is the founder of Hearts2Heal, an Austin, Texas, group that creates culturally relevant mental health and wellness programming for people of color.

Nationally, about 1 in 3 Black adults who need mental health care receive it. The American Psychiatric Association finds they also are more likely to access such care through emergency rooms or primary doctors than from mental health specialists.

Sharli Berry, a licensed therapist in Tempe and member of the Black Mental Health in AZ coalition, said lack of finances, transportation, access to health insurance and the stigma surrounding therapy may prevent people of color from seeking treatment.

“I’ve definitely had clients that have come in and said, ‘You’re not going to tell people I’m here, right?’” Berry said. “We are doing our best to get rid of that stigma. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard, ‘Therapy is for white people.’”

Berry said she had no idea while growing up what a therapist was or that mental health counseling even was an option. She’s not alone.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 14% of Black adults received any mental health treatment in 2019 compared with 23% of whites. Of those seeking treatment, 8% of Black patients got counseling or therapy, compared with 11% of whites.

Yet, 17% of Black Americans 18 or older reported having a mental illness in 2019, and 23% of those reported a serious mental illness, according to data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

COVID-19 has made a bad situation worse. Black Americans, who are twice as likely as whites to die from the disease, have also been disproportionately affected by the economic ripples of the yearlong pandemic.

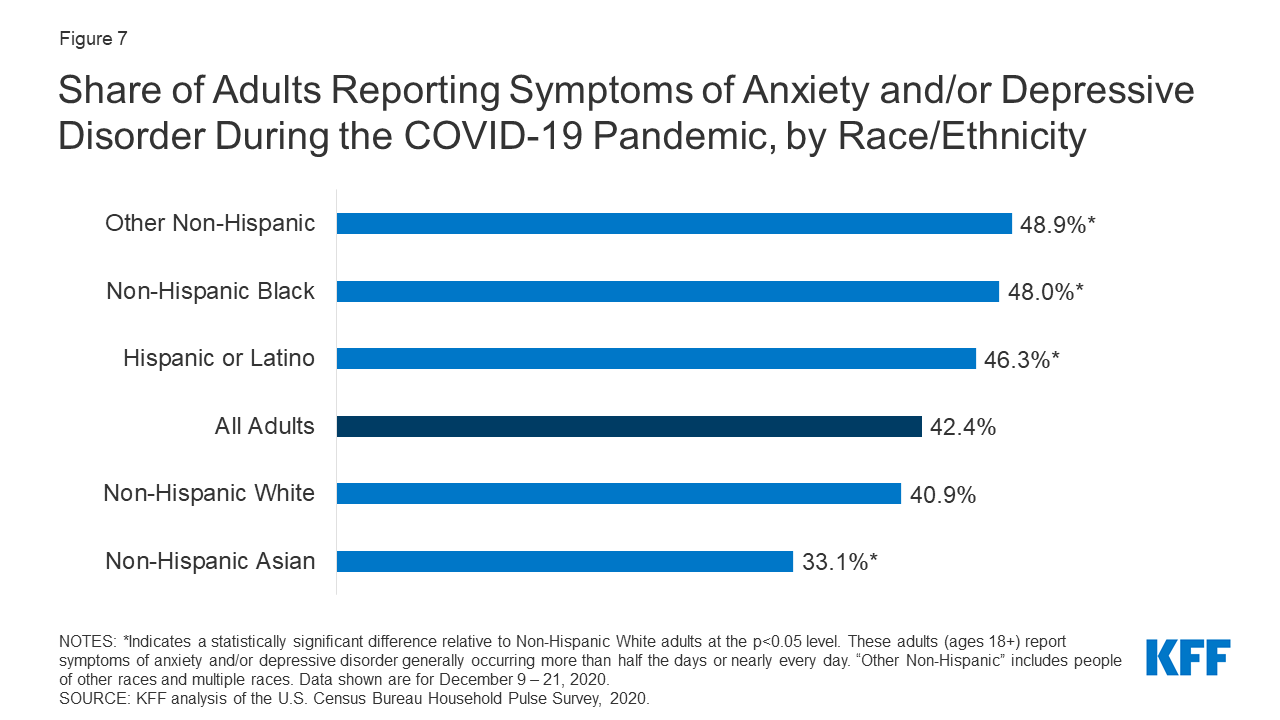

The Kaiser Family Foundation found that Black and Hispanic adults have been more likely than whites to report symptoms of anxiety or a depressive disorder during the pandemic, even though disparities remain in getting help.

Paul Gionfriddo, CEO of Mental Health America, notes the pandemic – and its accompanying grief from isolation and the financial and human costs – is just one factor related to mental health concerns for Black people.

Last summer’s protests over the police killings of Black men and women only compounded feelings of hopelessness and defeat, he said.

“Trauma builds on other trauma,” Gionfriddo said. “The people who are dealing with these societal strikes at the start are much more deeply impacted negatively than people who have grown up with the privileges of having wealth, living in safe communities or living in areas where there have been plenty of services.”

Nia Jones, a consultant with the Black Mental Health Alliance in Baltimore, said racism directly impacts a person’s mental health, whether experienced firsthand in everyday life or from hearing about violent incidents on the news.

“When we experience things like microaggressions, which aren’t micro at all, having to constantly turn within and deal with what we’ve seen on TV and what we have experienced in our daily lives causes that hypervigilance that comes with anxiety,” Jones said. “It causes that sadness that comes with depression.”

Berry said the community is tired, especially Black men who see themselves in the images of police shooting victims, including Michael Brown, Dion Johnson and George Floyd. After such incidents, she has had patients walk into her office and say: “I can’t do this.”

“Having to process and work through that and understand that every time they walk out of the house – they’re on edge,” Berry said. “They don’t know (if) they’re going to come home that night to their family.”

Gionfriddo believes systemic racism is an additional barrier to quality mental health care.

“I’m not really talking about racial bias when I say racism is a factor,” he said. “I’m talking about the structural kind of systemic building blocks of our society that have been built on the premise of inequity and inequality, as opposed to equality and equity.”

To combat these inequities, Mental Health America calls for improving access to mental health screenings for Black people, as well as providing more accessible information about what options are available to them.

“We know the best way to deal with mental health problems, like any other chronic condition – cancer, heart disease or whatever it is – is to screen for it,” Gionfriddo said.

Brown-Spence said it will take education on all fronts and “your everyday boots on the ground” people – neighbors, friends and colleagues – to help better identify when someone is struggling.

In addition to hosting peer support groups, workshops and seminars, Hearts2Heal offers a Mental Health First Aid training course to help people identify, understand and respond to signs of mental illness or addiction.

“It’s not always the clinician, because it takes time and resources to even get to that space,” Brown-Spence said. “We need to have more dialogues like these to say … here’s what you can do right where they are.”