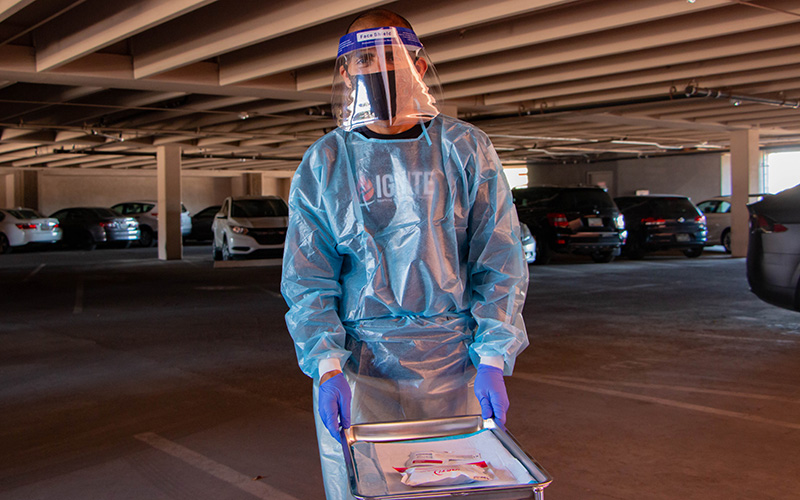

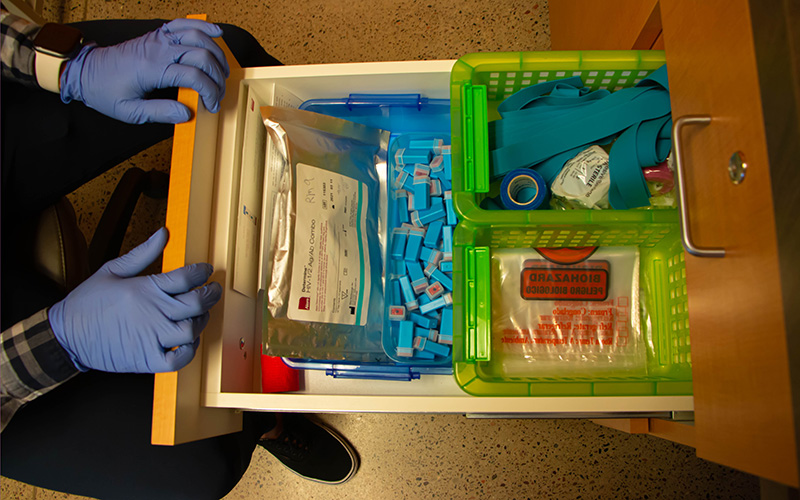

PHOENIX – In a downtown parking garage, a health care worker, dressed in protective gear, waits for cars to pull up for drive-thru HIV tests. Inside the building, volunteers assemble packages of at-home tests and condoms to be shipped across the state.

Elsewhere in metro Phoenix, a van travels to neighborhoods whose residents may face higher risk of infection to provide regular HIV testing, while doctors and case managers across the area respond to telehealth appointments by phone and Zoom.

Although face-to-face interactions have been the preferred method for testing and treating people for HIV and supporting them in vulnerable moments, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced local health care providers to get creative and adapt.

Such services as Zoom appointments, along with drive-thru, at-home and mobile testing, epitomize this new normal.

Dr. Ann Khalsa, an HIV specialist with more than 30 years of experience, has been part of the shift. She serves as medical director at Valleywise Community Health Center-McDowell, and spends most days on Zoom and phone calls with patients.

Khalsa said that amid COVID-19 – with so many people “hunkered down” and not prioritizing other medical needs – her clinic has seen a 30% decrease in people getting tested for HIV and linked to treatment.

However, some of the changes in delivery of care are helping, she added, and are likely here to stay.

“I think telehealth isn’t going to go away entirely because it’s too effective, too convenient,” she said. “Most of what we’re doing is counseling and reviewing lab data and talking with people.”

The ability to continue testing and getting people into treatment is particularly important in Phoenix, which is one of almost 200 cities worldwide that participates in the U.N.’s Fast Track Cities initiative to reduce new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths to zero.

As of 2019, 18,462 people were living with HIV in Arizona, with 776 new cases that year, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services. The incidence rate was highest among Black people, at 36.5 per 100,000.

In Maricopa County alone, an estimated 12,657 people were living with HIV in 2019, with 521 new diagnoses that year. The county, with nearly 4.5 million people, is Arizona’s largest.

Based on limited data, experts believe that individuals who have HIV and are being treated face no greater risks from COVID-19 than those who don’t have the virus, but people who are HIV positive and don’t yet know it or who aren’t in treatment could have a harder time fighting COVID-19 because their immune systems are weaker.

Given high numbers of both HIV and COVID-19 in Maricopa County, advocates in the HIV service community said a wider variety of testing and treatment options is vital.

“We’ve adapted in a way that makes a whole lot of sense,” said Rocko Cook, director of community services at Phoenix’s Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS, which helps about 30,000 Arizonans annually.

After the pandemic was declared last March, the center began offering drive-thru finger-prick tests in its parking garage as well as more telehealth options. In-person visits are possible but limited, to give staff time to sanitize rooms between appointments.

When Gov. Doug Ducey issued a stay-at-home order for a month and a half last April into May, Aunt Rita’s Foundation saw requests for free home HIV test kits almost triple.

“That part of our business exploded,” said Glen Spencer, executive director of the Phoenix nonprofit, which provides grant funding for HIV prevention programs as well as its own outreach and testing services.

Despite the pandemic, Aunt Rita’s was able to provide about $140,000 in grants last year – similar to past efforts, Spencer said. But he worries there won’t be as much money available in 2021.

“Some (fundraising events) have been postponed … and others have gone to a virtual format instead of in person, which we know will affect our fundraising at those events,” he said.

As someone living with HIV for 18 years, Spencer said he has experienced the stress that comes with seeking treatment after a positive diagnosis, and knows how in-person consultations can be beneficial to a person’s emotional well-being.

“You have lots of questions and lots of fears and lots of concerns about your future, and whether you’re going to have a future,” he said.

“There’s no substitute for being able to speak with an individual face to face in person. … That’s been a real loss for community outreach efforts.”

But there are benefits to virtual treatment. Added confidentiality is one, said Maclovia Morales, director of the HIV program for Native Health in Phoenix and a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation. That’s especially key in Native American communities, where the stigma associated with HIV may keep some from getting tested or treatment.

“When you go into a community center or clinic, you’re automatically singled out like, ‘Oh, what are they doing there? …That’s where they go to get tested for STDs,’” Morales said. “Walking into those types of situations, it’s almost like you don’t have that confidentiality.”

But with virtual consultations and treatment, she said, “No one knows you’re requesting it, the results are confidential.”

Cook, of the Southwest Center, sees other benefits in online support.

Brochures with educational information about HIV await visitors in the front office of Ebony House in downtown Phoenix. (Photo by Kamilah Williams/Special for Cronkite News)

Patients “tend to open up when they’re in their own homes; it’s a comfortable experience for them,” he said. “The experience of waiting on a test result with someone virtually in their home is kind of an interesting experience, as well. It does make it possible to have some great conversations around harm reduction and referrals.”

As experts and advocates push toward ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic, HIV testing has become more of a focus in past years, but it’s just one of the three pillars of HIV prevention.

The second is to get people who are HIV-negative but still at risk of infection on preexposure prophylaxis – medication that can help prevent the virus. And the last is to treat those who do test positive, to help suppress the virus and prevent transmission.

“It’s not that we can cure those who are living with it, but we don’t need to see new infections at all anymore,” Khalsa said. “To do that, we need to get everyone tested if they haven’t been.”

Ebony House, a Phoenix nonprofit that helps the Black community with HIV prevention and behavioral health, had to stop in-person testing for half of 2020 because of COVID-19, outreach coordinator Angelica Lindsey-Ali said.

The organization turned to self-testing and telehealth services, and it has a testing van that visits predominantly Black neighborhoods.

“We were actually the first agency in the state of Arizona, the first community-based agency, that offered van-based testing,” Lindsey-Ali said.

Lindsey-Ali sees similarities between HIV and COVID-19, in the misinformation surrounding both viruses and the fear.

“I’m 45 and grew up in an age where HIV was this big scary thing,” she said. “COVID is a lot like HIV. … People don’t want to wear a mask, they don’t want to wear condoms; there are readily available free COVID tests, people don’t want to get HIV tests.”

While COVID-19 has forced these organizations to adapt their services in the short term, it has also prompted them to reevaluate practices and determine what changes should be made permanent – or ways to be better prepared when the next crisis comes.

“When the pandemic hit and we had to shift the way we did services, we needed technology to support those efforts and we weren’t ready,” said Morales of Native Health, adding that shortages of basic supplies like gloves and hand sanitizer were also a problem.

Insurance coverage has been another challenge as appointments shift online, Khalsa said, adding that some companies want to pay less for not seeing patients in person.

Too often, she said, patients see lack of insurance as a barrier to getting the care they need, and they should know that there are places, including Valleywise Community Health, providing free HIV testing and services.

“So please don’t just say, ‘Oh my God, I lost insurance. … I can’t do anything’ and let whatever disease process you may have go untreated,” Khalsa said. “Please, please come in – because we can treat you.”

Added Spencer, of Aunt Rita’s Foundation: “It’s hard enough for people to pick up the phone and reach out sometimes and admit they need help. I encourage anyone who needs help to do so. We’re always going to be a friendly ear and a friendly voice.”