WASHINGTON – About 180 white tombstones – each belonging to a child who died while attending the Carlisle Indian Industrial School – stand row-by-row in the dewy grass of central Pennsylvania, bearing the names of those who died while being forced to learn the white man’s way.

From 1,500 to 1,800 Native American students from Oklahoma attended the Carlisle school, said Jim Gerenscer, co-director of the Carlisle Indian School Project, a database that provides information about the school and the students who attended. But some never made it back home, dying from unknown causes at Carlisle.

The purpose of school, as well as others across the nation, was to remove Native Americans from their cultures and lifestyles and assimilate them into the white man’s world.

Carlisle, which opened in 1879 and operated until 1918, was among the first and best-known boarding schools for Native children, and its operational model set the standard for most that came after.

For many tribes in Oklahoma, the horrors of the Carlisle model were experienced closer to home.

Riverside Indian School, outside Anadarko, is the nation’s oldest federally operated American Indian boarding school. Organized by Quaker missionaries in 1871, it was known as the Wichita-Caddo School until 1878.

Joe and Ethil Wheeler were educated there. Anthony Galindo, the grandson they raised, recalls hearing their stories about conditions at the school.

Ethil was one of many students who tried to run away from Riverside but always was sent back. Eventually, she was loaded into a cattle car and shipped by train in the dead of winter to Phoenix, where she stayed until she was 19. Galindo said his grandmother remembered huddling together with other children to keep warm. Some didn’t survive the journey.

Joe was abused at Riverside, Galindo said, and he never forgave. But as much as he held on to that grudge, he said, Joe clung to his belief in the creator, part of the traditional Big Drum religion practiced by Wichita people.

“First they cut my hair, then they made me eat soap and then they beat me for speaking my language,” Galindo said, recalling his grandfather’s words.

Joe’s father found out his son was being tortured at Riverside and removed him. Having learned English and completed the sixth grade, Joe became an interpreter for his people to assist in dealings between the federal government and the tribe.

Although many of the Indian boarding schools have closed, Riverside, now run by the Bureau of Indian Education, remains open. All that remains of the original Wichita-Caddo School campus is an eerily sparse graveyard atop a hill.

Quinton Roman Nose, a Cheyenne Arapaho who is president and chairman of the Riverside Advisory School Board, said some schools are operated by the tribes under old treaties with the federal government. The treaties often included an educational component; the boarding schools today derived from components within the old treaties, making education the tribe’s responsibility.

Officials at Riverside and the Bureau of Indian Education did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

The trauma from Riverside Indian School stayed with Joe Wheeler all his life, Galindo said. In fact, Joe’s feelings about Riverside make up Galindo’s first memory of being raised by his grandparents. Joe told him the government’s purpose was to wipe the Wichita people off the face of the Earth through cultural assimilation.

Richard H. Pratt, founder and superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, championed efforts to strip Native students of their cultures.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one, and that high sanction of his destruction has been an enormous factor in promoting Indian massacres,” Pratt said in an 1892 speech.

“In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Gerencser, with the Carlisle Indian School Project, said Pratt got the idea for the Carlisle school as an Army officer in Oklahoma Territory. While moving 70 Native captives to Florida, he said, Pratt invited Floridians to teach the prisoners English.

“So that’s where Pratt got this idea that, ‘Hey, if you isolate them from their families and their tribal life and you immerse them in standard American white culture, they’ll be just like everybody else,’” Gerencser said.

Unlike other boarding schools, Carlisle housed older students, with some enrolling as old as 18. Many boarding schools, including Riverside, recruited much younger students.

And not all boarding school experiences were abysmal.

“The boarding school experience that many people had in other schools just doesn’t seem reflected quite as much at Carlisle,” Gerencser said. “I mean, again, the concept is horrid, you know, why the school exists, but how you implement the assimilation process can be very different.”

By the time students – including Olympic champion Jim Thorpe – arrived at the boarding school in Carlisle, most already had attended primary schools on tribal reservations, and many students had experienced assimilation schooling throughout their lives.

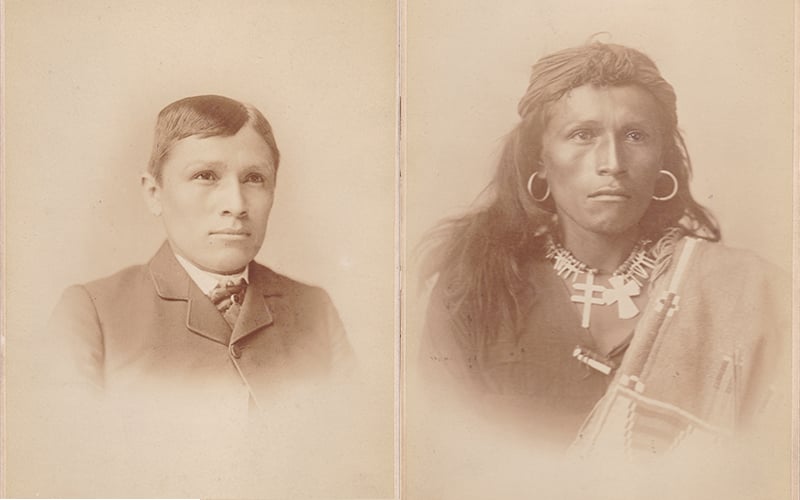

Left: Three Sioux boys pose at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School at the beginning of the assimilation process. Right: The same Sioux boys pose six months later. (Photos courtesy of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center)

Gerencser said the majority of stories from boarding schools were negative, but letters written to Pratt in 1890 show that some graduates found the Carlisle experience to be positive.

“It’s complicated,” Gerencser said. “I mean, no matter how you slice it, it’s really complicated and everybody’s experiences can be very, very different.”

The recruitment process for Carlisle also was different. In the beginning, Pratt traveled to reservations across the nation, promoting the boarding school and its purpose.

“We don’t know exactly what he was telling the chiefs and headmen that were gathered there,” Gerencser said. “So we have no idea necessarily what kind of promises Pratt might have been making about his view of the importance of going to the school.”

Contributors to the Carlisle Indian School Project, however, visited the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho last year to hear about tribal members who attended the Pennsylvania school. One woman said her great-grandfather’s mother chose to send him to Carlisle when he was only 10.

The woman said her great-grandfather was among the Nez Perce who had been captured by federal troops in the late 1870s after tribal members fought the forced relocation to a reservation.

“They are prisoners of war,” Gerencser said. “They are living in terrible conditions. This woman’s husband and older son had already been killed in the wars, and she’s in a desperate situation. So, yeah, she’s making the choice, but what kind of choice is that?”

In Carlisle’s later years, the school began to gain an international reputation with its band and football team going on tour across the country, as well as Thorpe’s fame.

Gerencser, who also is the Dickinson College archivist in Carlisle, reiterated that, although Carlisle’s purpose was the same as other boarding schools, it operated in different ways.

“One of the things you always hear about is how no one’s permitted to speak English and you’ll be punished if you do speak your native language, right?” he said. “Well, there’s a newspaper article about three years after the school had started saying all the students want to learn Sioux. That’s not going to be printed in the paper if, you know, it’s that taboo of a thing.”

Although many Native Americans chose to attend or send their children to Carlisle, the intent of the school was, from the first day, to destroy tribal cultures. When the first group of students arrived at the school, white names were written on a blackboard.

“The students would be handed a pointer and told to point at one of those names, and then that was written on a piece of paper and hung around their neck,” Gerencser said.

Boarding schools across the country made it difficult for tribes to preserve their cultures, practices and languages. Some students readapted to life on the reservation after graduating, but the loss of indigenous cultures was widespread.

Perhaps the most famous images taken at Carlisle were of Tom Torlino, a Navajo student in 1882.

In one photo, Torlino is photographed arriving at Carlisle with long hair and wearing tribal garb. In a photo taken six month later, he has short, styled hair and is wearing a suit.

“One of the other things that people often think is that every student that went to Carlisle would have this kind of before photo taken, and the fact of the matter is they only did that maybe two dozen times all together,” Gerencser said. “They just needed a few representative samples to use for their propaganda.”

About 8,000 students attended Carlisle, he said, “and for every student there’s a different story of how you got there, why you were there, what your experience was like.”

The stories passed down from those who attended such schools as Riverside and Carlisle are reminders of the resilience of Native people across the nation, but the cemeteries that remain – and the names of children etched in marble – are emotional reminders of the stories that have never been told.

Gaylord News is a Washington-based reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication. Cronkite News has partnered with OU to expand coverage of indigenous communities.