PHOENIX – May Tiwamangkala remembers mornings at Perryville Prison west of Phoenix, when the Wildland Fire Crew members began chanting and stomping their feet on concrete to let the rest of the prison know it was 5 a.m.

On their training runs, she recalls, one veteran on the all-women crew would shout, “Who are we?”

“Fire crew!”

Her next shout: “Be phenomenal!”

“Or be forgotten!”

The Perryville crew is one of 12 17-person crews of incarcerated firefighters in Arizona, and the only crew of all women. But once crew members leave prison, they often face difficulty getting hired as firefighters, typically because they lack documentation of their work or can’t get required certification as emergency medical technicians because of their criminal records.

That was true in California, too, but in September, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill to expunge the records of formerly incarcerated firefighters, allowing them to receive an EMT certification, which most city fire departments require.

In Arizona, state legislators are looking at a change that wouldn’t go nearly as far but would help prison firefighters earn earlier releases.

For decades, men and women in prison have worked to battle wildfires in states throughout the West. Since the program came to Arizona in the 1980s, many people serving time for less serious crimes have been trained to help with fire suppression across the state.

Their role has become more urgent in recent years: According to the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management, wildfires had burned 955,000 acres of Arizona in 2020 as of November, compared with 379,000 acres in 2019 and 161,000 acres in 2018.

According to the Arizona Department of Corrections, at least six prison fire crews and 113 incarcerated firefighters fought two of Arizona’s biggest wildfires last June, the Bighorn Fire outside Tucson and the Bush Fire in the Tonto National Forest northeast of Phoenix.

Incarcerated firefighters go through the same training as members of any public or private fire crew, said Tiffany Davila, public information officer for the Department of Forestry and Fire Management. They dig fire lines on active blazes, clear underbrush and cut down dead trees. But there’s a big difference between incarcerated firefighters and firefighters who are not in prison: how they’re compensated.

Incarcerated firefighters make 50 cents and $1.50 per hour, depending on the type of work they do, while public and private firefighters make a median of $22 per hour. However, because inmates are paid for the entire time they’re out fighting fires, they can make more money than at jobs inside the prison.

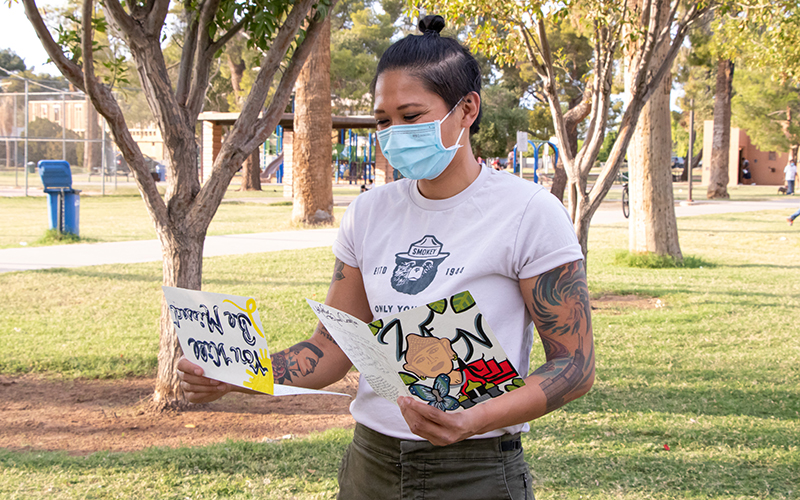

May Tiwamangkala looks back on the cards her fellow crew members wrote for her birthday and when she left Perryville Prison. All the members of prison fire crews interviewed for this story said developing sisterhood among crew members was a highlight of their time on the crew. (Photo by Sinead Hickey/Special for Cronkite News)

Fighting flames to reach redemption

Whether crew members find jobs in firefighting after their release or not, some agree that the less-tangible benefits of the program are the most important part.

Krista Countryman said she joined the prison fire crew after a decade of drug abuse landed her in Perryville Prison for the third time.

“I’d lost all contact with my family,” she said. “I had no professional skills and very little social skills. I had no home, no job, no car, no kind of life at all, really. Most of all, I had no hope for myself or the future. The fire crew changed that.”

Countryman said she began by setting simple goals.

“When you get out, those goals get a little bit bigger,” she said. “But it started with doing more pushups than the day before.”

Her ultimate goal, which she achieved, was to reunite with her daughter. Wanting to improve for their sake of their families was a common refrain for many women who joined the crew.

Tiwamangkala, who served a nearly three-year sentence for an aggravated DUI at Perryville, said she asked everyone she encountered how to get on fire crew so she could fulfill her desire for redemption. It eventually paid off.

Marnie Bryan was 47 when she joined the Perryville crew. She was the oldest member by about 10 years, she said, but that didn’t stop her from completing the rigorous physical training. She wanted to be proud of something while serving four years and three months.

Lynette Sandoval was on the fire crew for most of her sentence from 2017 to 2019 for running away from a halfway house after being in prison for drug offenses.

“I wanted to come home and be somebody else, somebody better,” she said.

When there weren’t active fires, the Perryville crew did chores and removed excess vegetation to prevent fires from spreading, a practice known as fire-wising. They left the prison at 5 a.m. each day and worked 12 hours before returning.

“I was getting to work outside all day in nature,” Countryman said. “I really felt like my time in prison wasn’t a waste of time.”

Sandoval said fighting active fires was both frightening and exciting.

“You get this emotion of being nervous or scared because it’s a fire, it could hurt you, but you also get this adrenaline rush and want to just go do it,” she said.

Before entering the program, women told Bryan it would be much worse than it was, describing such horrors as having to do burpees, a form of pushup that crew members said was used as punishment, in the desert next to raging fires. However, Bryan said she thinks sometimes people lie out of jealousy because of the program’s privileges and because you can only be on fire crew if you haven’t committed infractions behind bars.

For Bryan, the allure of being out in public was one of the draws of the program. When the crew would walk into a restaurant wearing their gear, she said, people would often clap and ask them about themselves.

The appreciation from the community gave Bryan goosebumps, and she cried sometimes.

“Everybody loves the firefighters,” she said. “And to be an all-women’s crew, people think we’re like the coolest thing ever.”

For Countryman, those interactions with the community helped her transition to life after prison because she knew what it meant to be passionate about work.

Countryman became a blue hat, or squad boss. She was the boss for chain saw operation, while two other women were squad bosses for fires.

“I cared about the program,” she said. “I cared about doing a good job. I cared about my other girls.”

Anyone coming to Marnie Bryan’s home will see this photo of her and the Perryville crew with Gov. Doug Ducey. “I’m proud of myself,” Bryan says of her time with the firefighters. “I’ve never been proud of anything I’ve done.” (Photo by Sinead Hickey/Special for Cronkite News)

On the record and the research

Lindsey Raisa Feldman, an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Memphis, studied Arizona’s Inmate Wildfire Program while working on her doctorate at the University of Arizona in 2016. As part of her research, she fought wildland fires alongside male prison crews and documented their experiences.

Feldman didn’t study the Perryville women’s crew, she said, because the small number of women would have made anonymity impossible.

She said the program is both exploitative and transformative because the way incarcerated firefighters are compensated reveals an “exploitation involved in prison labor fundamentally,” yet the program changes the people in it for the better.

“What I was hearing from the men with whom I worked was that it was a space of healing and it was a space of reclaiming dignity,” Feldman said.

Arizona’s program is different from those in California, she said, and in a good way.

In California, prisoners in the firefighting program live at fire camp for the duration of their sentence, according to Drew Smith, a battalion chief in the Los Angeles County Fire Department. His crews incorporate the prison crews as part of their “fire family,” he said, but a certain distance is maintained.

“We all treat each other very well, but we have to remember it’s not unicorns and rainbows for those people who, being in camp, are there for a reason,” Smith said.

As Feldman described in her research, crews in Arizona travel in fire buggies instead of prison vans, wear fire uniforms instead of prison uniforms, and leave prison for days at a time, interacting with the public along the way.

Feldman said those changes create space for participants to see themselves as more than criminals, something they don’t get in states where they live at fire camps for their entire sentence or work in clothing labeled prominently with prison letters.

In her job working in records at the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management, Krista Countryman makes it a point to inform formerly incarcerated people on all the details of how to become a firefighter. (Photo by Sinead Hickey/Special for Cronkite News)

No red carpet awaits

Seeing themselves as capable didn’t translate into jobs as firefighters for Bryan, Sandoval or Tiwamangkala.

Davila said Arizona hires former prisoners for wildland firefighter jobs, but those jobs are limited. Bryan, Sandoval and Tiwamangkala all said they didn’t have that chance or didn’t try because of personal reasons or other obstacles.

In Phoenix, for example, firefighters must be licensed EMTs, which can cost up to $1,000 to acquire, according to EMS University. Applicants also must pass a fingerprinting check and an extensive background check.

Countryman said she knows some people who were in the prison program who are EMTs now and others who were denied. Becoming an EMT with a criminal record, she said, is “not impossible but tricky.”

After her release, Countryman made accounts on USAJOBS and AZ State Jobs to apply for as many firefighting positions as possible. Those portals are the avenue to getting a firefighting job, which Countryman did, becoming an inaugural member of the Phoenix Crew, a state hotshot crew that hires former inmates of both genders.

Countryman describes her placement on the Phoenix Crew as “divine intervention.” Her early release from prison due to a paperwork mixup came just in time for her to apply.

Gov. Doug Ducey created the Phoenix Crew in 2017 to help reduce prison recidivism and give people a chance to give back after their sentences ended.

When state officials started the 17-member Phoenix Crew, Davila said, they had hundreds of applications, and they still get calls and emails from formerly incarcerated people interested in being on the crew.

Ducey isn’t the only Arizona politician working to improve opportunities for people who do service work while serving time.

State Rep. Walter Blackman, R-Snowflake, introduced legislation last year that would expand early release opportunities for inmates who participate in self-improvement programs, including fire crews.

Blackman’s bill, which he plans to introduce again this year, includes an opportunity specifically for prison firefighters to earn one day off their sentence for every two days they spend fighting fires or training.

“A lot of folks that are fighting wildland fires while incarcerated are doing Arizona justice by doing this because it’s an extremely dangerous job,” Blackman said. “In a sense, they are saving our natural resources.”

It’s important to help nonviolent offenders rehabilitate during their sentences, he said, especially those who are in prison because of drug addiction. Earned-release credits target that population because the Inmate Wildfire Program and other self-improvement programs are available only to them.

Feldman said lasting change will happen only when the public starts to care about inmates when they aren’t on the front lines fighting fires.

“When the fires die down, so, too, does the interest,” she said.

Lynette Sandoval has kept the picture of her fire crew standing with Gov. Doug Ducey. Outside Perryville Prison, the women wear firefighting uniforms just as any public or private firefighters would, rather than prison garb. (Photo by Sinead Hickey/Special for Cronkite News)

Looking back as they move forward

The lessons learned from their work on the Perryville crew have stayed with these women beyond their sentences.

Sandoval said she achieved her goal of becoming a better person. The lessons of fire crew include thinking things through, knowing she isn’t failing if she’s falling behind, and finding a way to push herself to overcome obstacles.

The women agreed the best part of being on fire crew was the sisterhood they built. Sandoval considers the others “part of my family.”

Tiwamangkala now works full time at TITLE Boxing Club as a personal trainer and boxing instructor after failing to become a firefighter because of paperwork problems.

“I know it’s a really competitive industry,” Tiwamangkala said. “So they kind of like, to me, they sold us a dream where really the opportunity isn’t what they made it seem.”

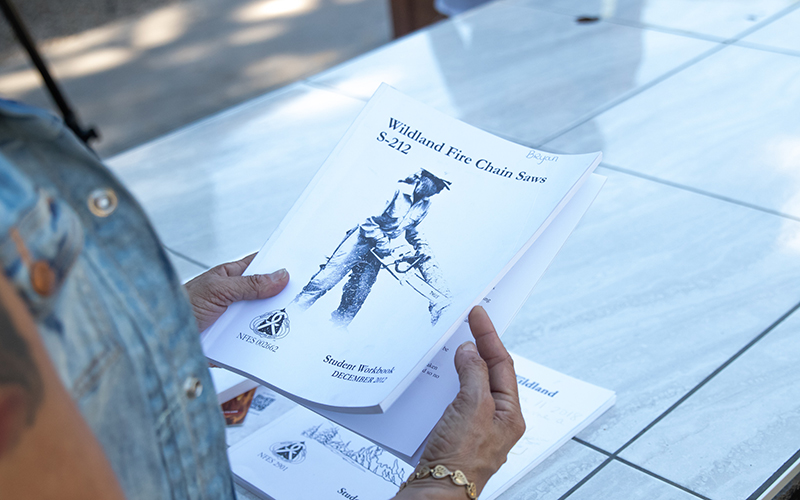

Tiwamangkala has a certificate in chain saw operation, a certificate that shows completion of wildland firefighter training and a handwritten fire log. Those certificates are the only official materials she has to show for her time, but firefighting job portals require more documentation.

Countryman said a lack of certificates is a common problem for formerly incarcerated people applying for firefighting jobs because inmates can’t use the internet individually. They take certification classes together and don’t receive individual documentation for the classes.

Those certifications are available on the website of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and are required to work for the state. Countryman said the classes only take about an hour each, but people aren’t told they will need to re-do those certifications once they leave prison. Countryman has an email with all the links and information about the certifications written out to send to people who fought fires in prison who are looking for jobs.

“The more stuff you can give them the better I think your chances are going to be,” she said.

Although the women haven’t all continued firefighting, they still see the impact of the program on their lives.

Bryan is a hairdresser now, which is what she did before going to prison. She said she wanted to be a firefighter but thought she was too old to apply.

When she cuts firefighters’ hair, she tells them with pride that she was a wildland firefighter.

Sandoval tried to join a crew immediately upon her release last June but didn’t make it past the interview. She said they told her to reapply in the future. She hasn’t reapplied yet because she has moved up at her job with U-Haul, but she still wants to work in firefighting some day.

“It felt like that was where I was supposed to be,” Sandoval said. “And I am definitely going to try and get back on there.”

Countryman recently switched to records management for the Department of Forestry and Fire Management so she could spend more time at home with her daughter, who just started high school. Although she was able to get a job as a firefighter, the most important skills she learned on the prison fire crew, such as self-worth and patience, are the ones that make her a good mother.

“I’m a good mom today,” she said. “That was probably, for a long time, my biggest regret, and now it’s my biggest accomplishment.”