PHOENIX – Most of 2020 has been marred by uncertainty.

The fickleness of daily routines. The indecision of divided leadership. The precariousness of an American lifeline, sports, as society once knew them.

What lies beyond the scope of doubt, however, is that formerly marginalized voices are headed to the podium to ignite tangible, national growth. College athletes want a seat at the table. Professionals have weighed the risks of competition in a COVID-19 climate versus the rewards. And adolescents dream on, despite some losing out on Friday nights under the lights and school dances. All in the face of a global pandemic.

Enter digitized health care databases. Leading the way is PRIVIT, which doubles as a medical eligibility forms platform that caters to K-12 school districts, college and university athletic departments and professional and developmental sports organizations. Its clients include Clemson University, the USA Hockey National Team, the University of Southern California and close to a dozen state high school athletic associations. Its work supplements the shift to telehealth and data-gathering smartphone apps afoot in the health care industry.

Originally established in 2005, under a similar moniker, PRIVIT offers an electronic solution to paperwork. In 2017 it introduced the Sideline app, seeking to lessen the dangers of concussions in sports by simplifying the best course of action for coaches and athletic trainers. Now, it looks to capitalize on digital health care trends accelerated by a tumultuous year.

“It’s been brewing for a long time, but it’s kind of the thing that sparked the fire and I think patient-privacy, secure medical records, the convenience of being able to do it online – it’s going to be a big thing moving forward,” said Jodi Murphy, the company’s vice president of sales.

The issue she knows all too well, Murphy said, is that “a lot of student-athletes who are fighting to get paid for being recognized as college athletes probably don’t even think about their medical records, and where they’re stored and who has access to them. I would just about guarantee, if you asked 100 kids, 95 of them have no idea and have never thought to ask.”

In part, because they’re blinded by what lies at stake performance-wise.

College athletes are generally held to high standards, both academically and athletically, and most are unaware or unconcerned that a 14-plus page packet filled out by hand upon their arrival to campus or team facilities may directly affect their livelihoods down the road.

“What’s attractive to (professional franchises) is if they’re going to be drafting a player from a college that uses PRIVIT, then that athlete can login to their portal, and their profile from all four or five years of college will go with them,” Murphy said. “They’ll have a much more comprehensive medical history and that’s obviously important in professional sports, no matter what sport.”

Administrators, compliance officers and medical personnel are able to assess an athlete’s entire health care history in a split second, via a customizable online profile.

“Maybe what happened at the University of Maryland wouldn’t have happened if they had an active medical record on that kid who had (a seizure), and then passed out when they were doing their workouts,” said Murphy, referencing the 2018 heatstroke death of Maryland football player Jordan McNair. “That’s probably the one thing that is a little more ideological, but very important to us as an organization and as a group.”

The first step and advantage for clients using the international company’s resources, PRIVIT believes, is digitization. Next comes ancillary benefits like safety, better care, risk mitigation and an increase in productivity.

“We really address it as this niche process that is absolutely mandatory across all of the markets that we work in,” said Russell Goodwin, CEO of PRIVIT. “We’re really helping replace a process, within these organizations that we work with, that is still primarily done by pen and paper.”

Digitized medical records for athletes and maintaining up-to-date profiles could play a big hand in overall improved health and safety of sports teams. (Photo By BSIP/UIG via Getty Images)

Breaking away from old-fashioned habits

The genesis of PRIVIT was rooted in a belief that student-athletes would benefit from a thorough, but totally digital and unbounded questionnaire during medical assessments.

Instead of filling out identical paperwork year after year, they would ideally revisit their own configurable profiles and update health-related information whenever time permits.

For example, if an athlete’s family member has sickle cell disease, or muscular dystrophy or even a peanut allergy, they’re able to flag notes on their profiles that could yield greater attentiveness to warning signs or high-risk conditions.

In practice, PRIVIT’s design would cut down on wait times, typically caused by answering redundant queries; assist physicians’ prescreening procedures; proffer medical personnel an extensive look at a student-athlete’s records, and trigger additional questions by personalizing the entire process.

“This is really important for colleges and universities because the medical eligibility, and all this information that they’re signing off on, it’s all to address a risk perspective,” Goodwin said. “By centralizing all of this information, they can now go back and reflect on (records from four to five years ago).”

Research conducted by Gordon Matheson, former Head of Stanford Sports Medicine and Head Team Physician for Stanford Athletics and the Golden State Warriors, helped determine electronic PPEs (pre-participation evaluations) are valuable tools to better understand aggregate injury and illness data in athletes.”

Matheson and Willem Meeuwisse, the medical director of the National Hockey League, are both regarded in the medical community as pre-screening experts. And both presently sit on PRIVIT’s Medical Advisory Board, alongside an esteemed list of colleagues, including Ohio State University’s senior vice president for alumni relations and former Buckeyes running back, Archie Griffin.

“The stuff that we didn’t really understand, at first, when we came to market, was aside from a medical questionnaire and doing a medical or physical examination, there’s all of this other stuff that is included as part of the eligibility protocol,” Goodwin said. “At the end of the day, there is really two things that you have to do as an NCAA student-athlete in order to step onto the field for the first practice of the year: You have to be cleared by the NCAA clearinghouse, which involves a number of things, and you have to be cleared, medically, by your school.”

Both boxes are checked — concussion education forms and various other orders of compliance are met — for PRIVIT’s growing list of clientele, which includes the National Junior College Athletic Association, an emerging number of competing universities in the United States and an assortment of higher-learning centers in Canada.

Similarly, PRIVIT is also being used at lower levels, like state high school athletic associations in Missouri, Georgia, Ohio, Michigan and Florida.

The company also aims to expand in the world of professional sports.

“They literally hand out a notebook with carbon paper, that’s like 50 pages, and it goes to the players and they fill out the first 20 and then it goes back to the office, and then the physicals get done and the doctors handwrite everything,” said Murphy, discussing the inner workings of many administrative hierarchies in the National Football League. “And then because of their CBA, all the players have to get a copy of everything, so they have to break down the book, take out the carbon paper and give the copies to the players, and then take the originals and scan them into a computer and upload them into their EMR system.

“I knew it was archaic, but I didn’t realize it was that archaic.”

Murphy said it’s simply a matter of cognizance.

“I think part of it is that they don’t really know it exists,” she said. “I think the other thing is, coaches, especially in the professional ranks, are getting younger – coaches, trainers and medical professionals. I think the old guard is starting to move forward, those guys who were really comfortable.”

Seven of the 32 head coaches in the NFL are 40 or younger, and young blood seemingly trends the strongest each hiring cycle — but there hasn’t been much budging, systematically, to date.

“If you need to go dig and find a specific piece of information, you’re going to spend hours sifting through PDFs or sheets of paper,” said Murphy, harking back to a conversation she had with a team’s representative. “It blew my mind when I got off the phone with them. I mean, the first thing I did was call Russ and say you’re not going to believe this.”

Their approach was outdated.

But it’s the same approach that doctors of medicine, like orthopedic specialist and founder and president of AzISKS (Arizona Institute for Sports, Knees and Shoulders) David Bailie, consider reliable.

“I’ve reviewed thousands and thousands of medical records on prospective athletes at all levels,” Bailie said. “Colleges are a little less stringent, but the pros, I mean, we get large files on pro athletes that we have to (sort) through, and then we order new tests, have to examine them and all that stuff, and it’s done by hand because we have to go through everything to see what’s important and what’s not important.

“The only way it would be more efficient would be if there were standard medical record-keeping, which there is not, so until that happens, any of these kinds of things are just going to be fraught with problems. No physician from a pro team is going to trust a database that the athlete has access to because they’re not going to be honest.”

Bailie has worked with “kind of the whole gamut” when it comes to athletics. He has served on a number of team medical staffs in professional sports circles, including the Phoenix Suns, Phoenix Mercury and Phoenix Coyotes, and has cared for Olympians, and student-athletes at every level of competition.

His gripe with a system that gives players increased controls over health care documentation comes from experience. Bailie has assessed human anatomy for longer than three decades.

“I just did an evaluation on an ex-NFL player… and he’s citing all these things that he did or didn’t have done over the years, in college or whatever, during his days in the NFL, and he misrepresented numerous things, mainly because he doesn’t have any medical knowledge,” Bailie said. “No offense, but many athletes don’t know where they’re going, any particular given week — but, yeah, nobody pays attention. Regular patients don’t even pay attention to their records until they need them.”

He’s doubly concerned by what dangers might arise from players trying to finesse certain protocols, or manipulate information, under the impression that it benefits their short-term performance. To illustrate, an athlete downplaying concussion symptoms, or leaving off a prior brain injury altogether could induce long-term consequences.

“For it to be reliable, it can be accessible to the athlete, but they would not be able to add anything to it, or remove anything from it. It would have to be secure so they can only read it,” Bailie said.

He is, however, a proponent of PRIVIT’s modus operandi, so long as it abides by privacy laws.

“If there was a place where teams could enter the data from high school, college and pro sports, and the medical staff of those could enter the data into this database for other teams to look at in the future, that may be one thing,” Bailie said.

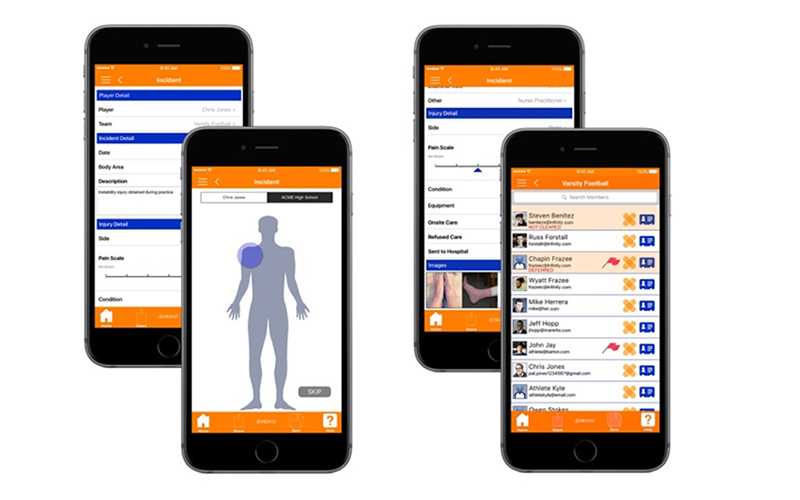

PRIVIT believes its Sideline app can help trainers and coaches recognize and record injuries faster by having easy access to health information. (Photo courtesy PRIVIT)

Improved testing

PRIVIT linked arms this fall with U.S. Med Test to capitalize on the international surge for increased distribution of COVID-19 testing materials, and implementation of protocols.

The partnership has granted any PRIVIT clients that express interest the means to test early, test often and register and monitor results, guaranteed to return inside a 48-hour window.

“I think the PRIVIT piece is vital, quite frankly, going forward,” the President of U.S. Med Test John Rosich said during a webinar

Rosich’s underlying goal, he said, is to accumulate enough data then make it available to national registries so that bureaucrats can make better decisions moving forward. This requires administering the right test, the right number of times per week.

It also requires PRIVIT’s reach within bustling communities. And their ability to store, manage and gauge test results and other key medical history in a “clean” system that heeds to international privacy laws.

Rosich quickly conveyed to Murphy he was forming a consortium of businesses to create a comprehensive, end-to-end testing platform that essentially kills two birds with one stone.

On one hand, PRIVIT procures tests and testing kits from U.S. Med Test. On the other hand, Rosich’s team provides personnel to run tests and collect samples, overseeing the full process.

Both aspects are equally important; tests are not cheap; margin for error is minuscule.

“There’s no such thing as a $5 test,” Rosich said. “And I’ll be honest with you, it’s not coming any time soon. It’s nonsensical, you just can’t even produce them for that price, and if you could, once you add everything on to it, there’s no way those logistics work.

“The last thing you want to do is go and speak to someone who is not very clear or very comfortable with what they’re saying and what they’re doing. … It shouldn’t surprise you that people kind of dig their heels in when it comes to interpreting what is going on from the medical point of view.”

Early in October, the two sides watched their visions collide in a pilot run.

Every student and staff member at Longview High School in East Texas was instructed to create a PRIVIT profile. Hundreds voluntarily filled out basic medical history, a symptom screening and signed online consent waivers. All of the necessary forms were finalized by the time U.S. Med Test folks arrived on site.

Oral swabs and PCR testing was done. Samples were directly delivered to a laboratory under contract, and results were sent right back through PRIVIT’s mobile app in a timely fashion.

“Regardless, of where we end up with COVID-19, you’re not going to have 30 people sitting in a waiting room anymore to fill out paperwork,” Murphy said. “I think there is definitely a lot of — especially after what we’ve gone through in 2020 — people being more conscientious about what is the health of my employee, and why do I have to know that? It’s public safety.”

By a different token, Bailie, the sports medicine specialist, strongly believes newer technology will have varying effects on a patient’s experience. His outfit, built on patient-centric care hasn’t changed, whatsoever, in the last eight months — he attributes the steadiness to his “niche practice.”

“Some stuff will enhance it,” Bailie said, “(such as) online rehab — most studies that have been done show patients, particularly motivated patients, can do their own rehab if they have the right instruction and feedback — but, also, it can hinder things as well, because really, medicine should be about face-to-face interaction and not interacting with a computer.”

Annemarie Alf, founder of Olympus Movement Performance in North County San Diego, recognizes the potential perks of newer technologies, but similarly doesn’t want to lose her hold on what she calls “the most important thing.”

Interpersonal relationships.

Making connections

“If we shift entirely to digital, I think we lose a lot of that, and I think that’s really important for myself, as a performance coach, and a rehab specialist, but I think it’s also very important for physicians to maintain and create those relationships with the athletes, too,” Alf said. “However, I (do) think there are benefits to the digital platforms, and digital information because it’s so easy.”

She cites a spike of handheld applications, 2020’s downturn in physical greetings and the seemingly ever-emerging emphasis on COVID-19-related restrictions and limitations.

She also warns against pitfalls of sophistication, torn over a battle between the future and present day.

“I’ve seen the flip-side where an athlete had (an) ACL repair just before (the pandemic) started,” Alf said, “and then they were not able to get in-person rehab, or in-person treatment…and then ended up really, really far behind in their rehab because when they’re trying to do it at home, virtually, on their own, no-one’s correcting their movement patterns, and no-one’s putting their hands on (them), and like actually mobilizing their knee and putting them through the (correct) range of motions.

“I think as a performance health care system, we need to remember that we also need to get to know our athletes, and we need to communicate with them and we need to have relationships with them.”

Alf’s stance echoes Bailie’s, and vice versa. Both also voiced, generally speaking, that athletes fail to accurately gauge their injury history.

“Intentional or not, one, they want to play, they don’t want to be limited,” said Alf, a former college athlete in her own right, who became a national champion water ski jumper at Arizona State University in 2001. “And two, sometimes, I do honestly, seriously feel that they don’t understand the importance of all the little injuries that they’ve had. (They) can tell me a lot about potential compensations and risk-factors going into their seasons. It also kind of helps us build, either a proper rehab program, or strength program for them, based off their past injuries.”

More often than not, she said athletes reveal more as time elapses: “The conversation continues and they’re like ‘oh, yeah this one time, I think I might’ve had a concussion’ and we’re like, we just asked you if you had any injuries…they sort of try to hide things, too.”

Like Bailie, Alf is well-versed in the world of sports. She is a longtime physical therapist; earned her doctorate after a 10-year stint as a performance and strength and conditioning coach; received a call right out of school to accept an international contract that paired her with the Chinese Olympic Gymnastics team for the 2012 summer games in London; joined San Diego Loyal soccer club to serve as the team’s performance and medical director in its inaugural season, and opened her own wellness center several years back that offers everything from PT and sports performance, to IV and PRP (platelet-rich plasma) therapies, in addition to a team of naturopathic doctors and nurse practitioners who tap into functional medicine.

Her background provides a unique vantage point. More information is better, she said. Learning the “ins-and-outs” of an athlete is critical to her daily routine. She thrives in an active setting. She’s a crossfit junkie, and an Ironman finisher. She’s also not too fond of what can, at times, be her most tedious role.

“Administrative work is probably my least favorite part of my job because it’s too time-consuming,” Alf said.

At Olympus, it is her duty to manually update the medical files of athletes she treats. On the pitch, it’s a similar process, only, thanks to evaporated funds and a timeline chock full of obstacles, Loyal, a first-year club, opted not to pursue a hi-tech platform for electronic documentation and sharing.

“We’ve just created a very basic template that we share across Google Drive for this year, but again, going forward, I think when you have a digital platform and it allows the sharing of an athlete’s information, especially in the professional setting or the collegiate setting where different athletic trainers can look at the information, coaching staffs can look at the information…it’s definitely a lot more optimal,” said Alf, reaffirming challenges posed in 2020 could henceforth alter administrative landscapes.

That’s where Murphy and Goodwin come back into the fold.

Overall, the PRIVIT team is comfortable operating in its corner of the market, and doesn’t foresee any colossal change to its primary customer base — that is, high school athletic districts scattered across the map — although, joint efforts could put their savvy technology in a multitude of environments.

Two of the likeliest areas for exponential growth are the college and university, and research sectors.

Of more than 400,000 active users in PRIVIT’s system, less than 30% hail from the former. And a teeny-tiny percentage stems from the other. About 55% of users between Canada and the United States are derived from high school domains. The rest are made up in youth sports organizations, leaving a lot of prospective ground to cover.

But action won’t amount, until curiosity peaks.

“I’ve reached out to the folks I know at Scottsdale Unified School district. We’ve reached out to Arizona State, and the University of Arizona. While there is some interest, it has not been a priority,” said Murphy, asserting confidence that PRIVIT will be highly sought-after in the wake of the pandemic.

Pivot to PRIVIT

Murphy’s know-how includes interacting with compliance deputies and cerebral sport’s minds, particularly in a major-conference football setting

She served as the Director of Sales at Front Rush, LLC., an acclaimed recruiting software, designed by coaches, and retained by over 9,500 teams at more than 850 institutions before switching gears a month into 2020.

“I could name 10 programs that would probably (make) your head explode, if you realized what they’re doing and how they’re doing it,” Murphy said. “It’s really against the law to be collecting medical information on a non-HIPAA-compliant platform. (It’s) a big problem right now in college athletics, and it’s a dumb thing to get busted for, if you want to know the truth.”

A wide range of experience in the university space culminated a decade or so earlier for Murphy, when she was hired to work under Arizona State football coach Dirk Koetter, as one of the Bowl Championship Series’ first non-coaching staff recruiting coordinators.

Her eyes gradually opened, she said, from 2006 to 2009, tirelessly plugging away, first for Koetter and then Dennis Erickson’s regime in the desert.

“Working side-by-side with the coaching staff and the compliance staff really opened my eyes to a lot of the things that you assume — when you’re sitting on one side of the table — are going to work, and then you actually get in the real-world scenario and if it’s 10 steps too long they’re just going to write it on a piece of paper,” Murphy said.

She gained insight. She gained practical application skills. Most importantly, perhaps, she gained respect.

Now she would like to see change.

“We would love everybody, every student-athlete in the country to have a PRIVIT profile if it was our druthers,” Murphy said. “The pandemic has shown all the cracks in the NCAA system.”

Dating to axed men’s and women’s NCAA basketball tournaments in the spring, programs far and wide have been forced to suspend competition of other sports, drop teams from future participation, and in worst-case scenarios, cease operations entirely.

Most pundits predict the financial toll of the coronavirus will be devastating, likely exceeding billions.

Murphy trusts PRIVIT is equipped to automate the medical clearance process, digitize health care history, make use of electronic PPEs and gather insurance and other consenting information at the opportune time.

“Everything is documented in a lot of European countries from a medical standpoint, and in the United States we don’t do that, right? Because everyone is all about privacy and the whole nine yards,” she said. “There is a place for that, but part of the reason our health care system is broken is because there’s not a consistent way to have information available to any health care provider that needs it…I’ve moved from state to state and I’ll tell you, it’s a nightmare, trying to get records, so that a new physician understands what your (medical) history has been.”

It would appear that sooner, rather than later is rising to a level of certainty predominantly foreign in 2020.