Left: Fiona Lowenstein, a freelance writer in New York City, first got sick with COVID-19 in March and was hospitalized overnight. But she says she remained ill until early June. “New symptoms just kept showing up.” Right: After discharge, Lowenstein believed the worst of the virus that causes COVID-19 had passed, but over the next three months, she developed new symptoms, including loss of smell, runny nose, sore throat and trouble breathing. (Photos courtesy of Fiona Lowenstein)

PHOENIX – Although most cases of COVID-19 appear to be mild with a recovery time of a few weeks, health experts are seeing more patients who suffer symptoms for months or get better only to relapse down the road.

These “long-haulers” may face organ damage or such debilitating symptoms that even climbing a flight of stairs can put them back in bed for days, experts say.

Experts estimate some 10% of COVID-19 patients – or hundreds of thousands in the U.S. alone – may fall into this category. And yet with more than 7 million total COVID cases so far across the nation, research specific to the long-hauler phenomenon is scant, and questions remain about what care and support these patients may need.

Long-haulers “have moved past the symptoms that are associated with acute COVID infection and are now experiencing a new subset of symptoms that are lasting a lot longer than we expected,” said David Putrino, director of rehabilitation innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System in New York City.

The most common, he said, are extreme fatigue, exercise intolerance, heart palpitations, shortness of breath and problems remembering or finding the right words.

“But then there is a big, wide range of symptoms that we’re seeing also, that range from swelling and numbness in the extremities, tingling down the arms and legs, GI (gastrointestinal) symptoms, lots of anxiety, issues with regulating temperature, dizziness, headaches, nausea,” Putrino said.

“They’re very episodic. You can be … having a good day and then suddenly you’ll feel a sort of an attack on your physiology. And they are very severe in terms of the way that they’re limiting individuals in their daily life.”

Fiona Lowenstein, 26, a freelance writer in New York City, said she first got sick March 13. She went to the emergency room with shortness of breath, consistent fevers and slight nausea, and was hospitalized.

When she was discharged March 17, Lowenstein – who has no underlying conditions that would make her more vulnerable to COVID-19 – was under the impression the worst was behind her. But she remained ill until early June, she said.

“New symptoms just kept showing up,” she recalled. “I remember I opened up a bottle of my favorite lavender essential oils and realized I couldn’t smell it.”

Lowenstein added gastrointestinal issues, a runny nose and sore throat to her new list of symptoms, but the effects went beyond the physical. She said she experienced panic, anxiety, fear and nightmares.

“I even started to have feelings and dreams of drowning and I couldn’t breathe. I had never had dreams like that before,” she said.

“I realized I wasn’t getting any better and realized this isn’t just a two-week virus.”

After discovering other long-haulers on social media, Lowenstein co-founded the Body Politic support group with her friend and fellow long-hauler, Sabrina Bleich.

What started as a blog with 30 followers soon became a support group for thousands of patients. Such questions as “How did you know when to go to the hospital?” and “What does the nasal swab feel like?” are common.

“The group was open to all patients,” Lowenstein said, “but I think part of the reason it has become a safe haven for long-haulers … is when you think of who is going to be the most active in a support group, it is the person that is sick for months.”

A missed opportunity?

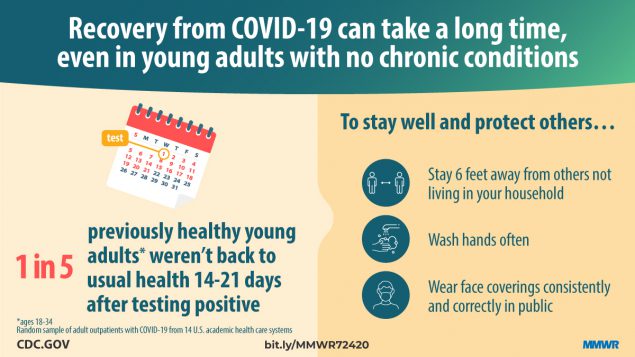

A report by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published in late July found that 35% of COVID-19 patients had not returned to their usual state of health two to three weeks after diagnosis. Additionally, it said, 1 in 5 people ages 18 to 34 and with no chronic medical conditions had not returned to their usual state of health.

The survey of 274 people included outpatient COVID-19 patients only, not those hospitalized.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, spoke about long-haulers during Senate testimony Sept. 23, noting a number of individuals have reported persistent symptoms for weeks or months.

“They have fatigue, myalgia, fever … as well as cognitive abnormalities,” Fauci said.

The issue is one federal researchers will be “pursuing in the future,” he said, adding that a number of people who recovered from COVID-19 were later diagnosed with heart inflammation.

“These are the kind of things that tell us that we must be humble and that we do not completely understand the nature of this illness,” Fauci said.

Efrem Lim, assistant professor at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute, leads a team that studies the virus’ potential to spread, mutate and adapt over time.

Lim refers to long-haulers as an “important and underlying problem” in understanding the development of COVID-19.

“We have this subset of people – the estimates are about 10 to 15% of people who develop COVID-19 – having these long-term symptoms, stretching out to months, much longer than the two- to three-week window that we are used to seeing.”

Lim’s research team has proposed long-hauler studies to the National Institutes of Health but awaits approval. The challenge, Lim said, is convincing the NIH to fund such a resource-intensive study that would require patients to be tracked for months.

Dr. Haider Warraich, a cardiologist and clinical researcher in Boston, said during a recent webinar about long-haulers that the United States is lagging in information and research.

“We are really missing an opportunity to really understand this disease – not only its acute phase but also thinking about the long-term impact of this disease on patients,” he said. “Right now, there is such an appetite for more knowledge and more insights into this virus.”

Warraich mentioned a patient who developed heart failure after having COVID-19. More than a month after his diagnosis, the patient’s legs began to fill with fluid and, Warraich said, “by the time he came back to hospital, he was actually way sicker than he was before.”

When COVID-19 began ravaging New York City, Putrino and his team created a remote system to monitor patients who weren’t being hospitalized. He soon noticed that some who had joined the program in March still were seeking help months later.

By May, he said, “there was this percentage of patients who had been on for a couple of months, and they were still sick but they were reporting new symptoms. So we started to train up a team … to manage the care of these patients.”

Most striking about the long-hauler patients, Putrino said, is they are on average 42 years old, 70% are women and many never were hospitalized for COVID-19.

His team continues to log data in hopes of improving treatment for these patients and is sharing that research with others around the country. Putrino wants to see the understanding of long-haulers grow, as well as research and programs to help assist them in their recovery process.

“We need more awareness in the form of generating content to educate both patients and doctors about this,” he said. “The second thing that we really, really need is more individuals in states that are just getting over their first surge to start allocating resources to treating these patients.”

Left: Fiona Lowenstein, a healthy 26-year-old before contracting COVID-19, calls her hospital stay surreal. She remembers the panic that set in as she recalled stories she’d read about COVID patients being hospitalized and never leaving. Right: Lowenstein recovered after three months with prolonged COVID-19 symptoms. With a mask and gloves on, she finally ventured out to the supermarket, one of the public places she avoided while ill. (Photos courtesy of Fiona Lowenstein)

‘This is a thing … it’s not just anxiety or stress’

Nearly 3,000 miles west, in Berkeley, California, Lisa McCorkell, 28, hit her six-month mark of COVID-19 symptoms in September.

She experienced her first symptoms on March 14, but she was able to access only one test, which turned out to be a false negative – something experts say is common.

“At the beginning, it was a lot of fatigue and shortness of breath, high heart rate, some brain fog, and I even had the COVID toes, nausea, dizziness,” said McCorkell, a policy analyst for the California Department of Social Services. “And then it kind of waxed and waned over the last six months.”

McCorkell wanted to become part of the solution and contribute to the limited research available on long-haulers. She joined Body Politic and helped develop a survey that aims to identify patterns in long-hauler symptoms and recovery times.

“The No. 1 goal is acknowledgement that this is an issue that is affecting … people, and hopefully that acknowledgment will spur more research into finding out what exactly is going on,” said McCorkell, who also had no underlying conditions.

The survey results captured a variety of symptoms and documented recovery time, accessibility to COVID-19 tests and the mental health of long-hauler patients, among other areas.

Nearly 650 people have responded, although McCorkell said Body Politic wants to get a wider range of respondents.

“One of the issues we are seeing is that most of our respondents are white and we know that COVID is affecting the Black and Latinx community particularly hard, so that is something we are trying to push,” she said.

Lowenstein and McCorkell said they hope to see advances within the medical community to increase awareness about the long-hauler experience.

“We want acknowledgment from doctors that this is a thing,” McCorkell said, “that this is not something that people are just making up in their heads, that it’s not just anxiety or stress.”

Today, even walks around the neighborhood can test McCorkell’s strength. If she pushes too hard, she can relapse.

“Fatigue is the one consistent symptom that I have been experiencing,” she said.

As for Lowenstein, only after quarantining for more than a month did she feel both physically and mentally capable of stepping outside her home for the first time – with a mask and gloves.

It took nearly three months for her to build the courage to get back on her bike and ride to the supermarket, something she’d never thought twice about before COVID-19.

“There are so many people that are unable to return to their normal way of life after being sick for such a long period of time,” Lowenstein said. “It’s time for people, health care professionals especially, to start understanding, acknowledging and researching long-haulers in hopes of creating more resources and awareness.”