Most kids entering juvenile detention have been disadvantaged by poverty and lack of resources, and more than 70% have mental health disorders that often go unseen and untreated, experts say.

Mental health resources vary widely among states and often fail to treat underlying issues said Charlene Taylor, a senior researcher for the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, a nonprofit that researches and supports nationwide juvenile justice reforms.

“A lot of times kids end up in the juvenile justice system based on mental health issues that are unaddressed or under-addressed,” Taylor said. “I don’t know if the resources have increased to balance the need.”

Arrested at 14 for aggravated robbery with a weapon, Lexie Alvarado of Denver cycled in and out of the system. The three facilities where she served time worsened her mental health struggles, resulting in aggressive behavior and fights, she said.

“My mental health … got worse when I was put in jail. It just made it hard … to be in there,” said Alvarado, now 21, who was diagnosed with PTSD, anxiety and depression during her time in Colorado juvenile detention centers.

“You’re there with a lot of younger people, so emotions are really high,” said Alvarado, who was released in March.

Lexie Alvarado, second from the left, sits with a staff member and two fellow residents outside a Colorado juvenile facility. Alvarado, who suffers from PTSD, anxiety and depression, spent ages 14 to 21 in and out of three Colorado facilities. (Photo courtesy of Lexie Alvarado)

Natalie Baddour, a licensed therapist with Youth for Christ in Denver, has mentored Alvarado for the past year, providing emotional support and guidance on reentering society. Of the 250 incarcerated youth Baddour has worked with, she said 97% were diagnosed with a mental health disorder, and 48% were diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Every one of our young people have some sort of mental health (issue) that’s been trickled down, whether generationally or just because of their trauma,” Baddour said.

Alvarado spent more than a year from 2017 to 2018 at the Betty K. Marler Youth Services Center in Lakewood, where she said she took Risperdal, Ritalin and Prozac, which had been prescribed by a facility psychiatrist to subdue her during the day, and Seroquel at night to help her sleep.

Members of the medical staff rolled carts filled with colorful pills to common areas, and girls approached for their prescriptions when their names were called, Alvarado said.

Taylor said many young people who serve long-term sentences are dependent on medication for mental health issues arising from repressed early-childhood trauma. But when psychiatric medication is involved, she said, the need for additional resources and regular therapy becomes more pressing.

Therapeutic services are dependent on funding, and “it certainly is cheaper to medicate kids than it is to do other services,” said Karen Abram, a clinical psychologist and lead researcher for the Northwestern Juvenile Project, the first large-scale longitudinal study of the mental health of detained juveniles.

Ahmar Zaman, a clinical psychologist who conducts evaluations and therapy for incarcerated youth in Houston, noted that, especially for many kids from low-income communities, their first encounter with the mental health services comes by way of the juvenile justice system.

“They’ve never opened up to anybody; they have never spoken to anybody about their concerns,” Zaman said.

The National Commission on Correctional Healthcare recommends screenings to identify existing mental health issues upon entry into the justice system. As of 2015, only 24 states had formal requirements for mental health screening in detention, according to Juvenile Justice Geography, Policy, Practice & Statistics.

Even with the screenings, Zaman said, kids with mental health issues often slip through the cracks.

The reason behind acting out

Alvarado said the environment at Colorado’s Marler detention center was “really chaotic.”

Tension between residents and staff turned fights into riots, one of which resulted in Alvarado’s removal from Marler shortly before the state ended its contract with the company operating the center. The building now is used by the state, according to spokesperson Madlynn Ruble of the Colorado Department of Human Services.

News21 reached out to Rite of Passage, the organization that operated the facility at the time, but never received a response.

Alvarado was sent to a third facility for the remainder of her sentence. There, she said, her peers harassed her during group therapy sessions, so she relied on individual therapy sessions twice-a-week.

Alvarado said her therapist was the only person who was there for her. Unable to connect through friendships, Alvarado also struggled with staff.

“Staff would provoke you,” she said. “(They) have to know everything about us, our family situation and all that. So when you’re getting mad, they throw your family back in your face.”

Alvarado said she once stormed out of the cafeteria after breaking up with her girlfriend, a fellow resident. One of the correctional officers who escorted Alvarado to her room complained that her aggressive behavior stemmed from the home she grew up in. Alvarado said she exploded.

“He tried to restrain me and I pushed him,” she said, adding that her leg was broken when she was restrained.

For young people who still are developing cognitively, Zaman said, there are “limitations to self-reflection that they might not even realize that they might have issues or concerns or be experiencing symptoms that are in line with depression, anxiety or trauma.”

Nearly three-quarters of juveniles in the system experience mental health disorders, putting them at greater risk for suicidal behavior.

Lexie Alvarado says the state of her mental health depended on staff members working with her. “There could be some therapists that actually worked with you … on all your mental health issues,” she says. “But then there’s some that just meet with you because they have to meet with you for the week.” (Photo courtesy of Lexie Alvarado)

Of the estimated 61,000 detained youth in the U.S., about 36% had previously considered suicide and just less than 30% had attempted it, according to a 2015 study in the Journal of Correctional Health Care.

Boys are more likely to die by suicide, the study said, but girls attempt suicide at higher rates while using less violent methods.

However, Zaman pointed to a growing body of research showing that girls now are using more lethal methods in suicide attempts.

Taylor, with the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, noted that more girls in the juvenile justice system seem to experience mental problems than boys, but the difference is likely much smaller.

“A lot of boys and men will have some of these issues, but they’re not as willing to open up to somebody and to report those kinds of things,” Taylor said.

A 2014 study by the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention found half of youth with identifiable disorders did not receive appropriate services, with as many as 59% of the incarcerated kids not receiving treatment for mood and anxiety disorders.

Treatment programs that are offered often fail to address the root causes of behavior, said Stephanie Covington, co-director of the Institute for Relational Development and the Center for Gender and Justice in La Jolla, California. Many mental disorders manifest through violence, which prompts a law enforcement response, not a mental health response.

“It’s a flawed system. As a parent, if one of my kids had gone into that system, it would have been shattering,” Covington said.

Lost in the system

Sebrina Washington of North Charleston and her 16-year-old son, Xzavier Robertson, are navigating through South Carolina’s juvenile justice system.

During the past year, he has been in and out of detention facilities, and is currently serving time for a parole violation and other offenses.

“I want my son to be home, truthfully. But what I really want is for my son to receive the help that he needs,” Washington said. “When Xzavier turns 18 and he hasn’t had any help to deal with himself, how is he going to take on life?”

Sebrina Washington outside her home in North Charleston, South Carolina. Her son, Xzavier Robertson, 16, is in a Charleston juvenile facility while she fights for her son’s access to proper mental health treatment. “When Xzavier turns 18 and he hasn’t had any help to deal with himself, how is he going to take on life?” (Portrait taken remotely by Michele Abercrombie/News21)

As a child, Xzavier loved playing with his siblings, basketball and video games, his mother said. He also had a short fuse. She observed bursts of anger where Xzavier, even as a 4-year-old, would shut down and withdraw from his peers.

A single mother of four, Washington adjusted her hotel work schedule to align with Xzavier’s modified school day, making quick trips to school upon teachers’ requests to calm him down, she said.

After Xzavier’s arrest for burglary in May 2019, screening diagnosed him with PTSD, anxiety and borderline dysfunctional disorder, as well as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Washington said.

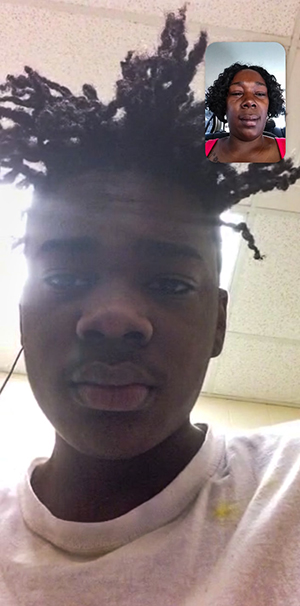

“I went to see Xzavier in jail and it made me well up in tears, (but) I couldn’t do it in front of him. … It’s like he’s lost, like he’s confused,” Sebrina Washinton says. COVID-19 restrictions have since limited visitation with her 16-year-old son in a Charleston, South Carolina, juvenile facility. She now sees Xzavier every Tuesday for 20 minutes via an app on her cellphone. (Photo courtesy of Sebrina Washington)

Xzavier was released after 84 days in detention under a sentence that acknowledged his mental health needs. Days later, he was arrested again and charged with probation violation, vandalism and assault. This summer, while awaiting resentencing, he stayed in a treatment center for juveniles 30 minutes’ drive from his family’s home.

Washington speaks to her son twice a week for 20 minutes at a time and, because of COVID-19 restrictions, only by phone.

“He’s saying he’s fine, but with Xzavier, he’s not a very expressive child,” Washington said. “I could tell from talking to him on the phone … he doesn’t want me to be worrying about him.”

Without her continued persistence, Washington said she fears that Xzavier will be “lost in the system.”

Lack of family involvement hinders behavioral progress for kids in the system, while family presence puts an advocate in the child’s corner and reduces anxiety, creating an effective environment for treatment, according to a 2016 report by the National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice.

Washington said a psychiatrist from South Carolina’s Department of Juvenile Justice this summer determined Xzavier’s mental health does not warrant alternative sentencing through yet another mental health screening.

She said Xzavier will finish his 12 to 18 month sentence in another facility two hours farther away that lacks the therapy programs he needs. He will be up for parole in September.

“It makes me feel like he was taken away from me,” Washington said. “This whole situation makes me feel close to death with my son.”

Discrepancy among states

States deal with mental health in a variety of ways, “from the appalling to the surprisingly sophisticated and well-funded,” said Robert Kinscherff, a clinical psychology faculty member at William James College and a member of the Center for Law, Brain and Behavior.

In Oregon, the state’s progressive approach toward mental health largely influences the department of corrections, said Ann Hutcheson, a former social worker at a boys correctional facility in Beaverton.

“Mental health treatment for juveniles varies depending on the culture of the state,” she said.

Even so, mental health services have not reached every child in the system, particularly those in the rural areas. That includes Shannon Rees’ daughter, Saraya, from Myrtle Point, who was 14 when she was sentenced to 11 years for two counts of attempted homicide and one count of attempted assault in 2019.

“There’s such a stigma involved that the mentally ill are criminal,” Rees said. “Saraya’s the sweetest little girl you’d ever meet. Just a normal, goofy, happy little girl that was having some issues in her own life.”

Although the degree of Saraya’s multiple diagnoses are yet to be identified due to her young age, Rees said, doctors have used such terms as major depressive disorder and social anxiety.

Saraya is among the 90% of all girls in Oregon’s juvenile system with identifiable mental health disorders as of January 2020, according to Oregon Youth Authority. At Oak Creek Youth Correctional Facility in Albany, she’s on medication that makes her seem tired, Rees said.

“She has one counselor,” her mother said. “They’re supposed to meet once a week, but … sometimes she goes up to three weeks with no counseling.”

Benjamin Chambers, communications director for Oregon Youth Authority, said Oak Creek has four mental health professionals on staff who work with parents on treatment plans, as well as “additional on-site hours provided by agency psychologists.”

“While we can’t speak to the services individual youth are receiving due to confidentiality concerns, we do seek to provide top-notch mental health and other support services to the youth we serve,” he said.

Like Sebrina Washington, Rees fears her child is falling through the cracks because of a lack of understanding of her daughter’s mental health, she said.

“Prison is not where we should be sending people for mental health care,” Rees said. “You can’t fix trauma with trauma.”

Saraya Rees is one year into her 11-year-sentence at an Oregon juvenile facility for two counts of attempted homicide and one count of attempted assault. Her mother, Shannon Rees, is sharing her daughter’s story to spread mental health awareness. “I won’t stop fighting even if it takes the whole 11 years,” she says (Photo courtesy of Shannon Rees)

For Lexie Alvarado in Denver, family is what helped her through her sentencing and motivated her to never return to the system after her release.

The word “Mom” is tattooed over Alvarado’s right temple, with a heart for the “o.” Of her many tattoos, Alvarado said this is her favorite.

Her most treasured decoration in her cell was a photo with her brother, Paul, wrapped in an embrace at her high school graduation, to celebrate the degree she earned in detention. Paul’s name also stays with Alvarado, tattooed along her jawline.

“The day I was being picked up and they told me to pack up my stuff. … It just felt so weird stepping onto the real world and actually not being inside of a gate,” she said. “The air kind of hit different that day. And then just spending time with my family, it was just like, it was like I actually belonged somewhere.”

In the weeks leading to her release, Alvarado lessened the use of her medication, with support from her therapists.

Alvarado said she no longer takes prescription medicine for her mental issues and feels stable.

“I just want people to view me as someone who made it out of the juvenile system,” Alvarado said. “I just want people to see me as someone different from who I used to be.”

Molly Kruse and Haillie Parker are Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation fellows.

If you or someone you know is in need of help, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255) or text 741-741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor right away.

This report is part of Kids Imprisoned, a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country. It is headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.