More than 1,600 incarcerated children across the country have tested positive for COVID-19 as of mid-August, leaving experts and youth advocates raising questions whether authorities are prepared to handle this and future public health crises.

Joshua Rovner, a lead researcher for the Sentencing Project, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy center, is tracking the number of reported positive COVID-19 cases in the juvenile justice system. He said many more cases are likely unreported.

“I really want to emphasize that these are only the cases we know about due to testing and reporting,” Rovner said in an email to News21. “The actual totals are definitely higher than these.”

According to data compiled by the Sentencing Project, cases have been found in 33 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

“No one in the United States was sufficiently prepared,” said Robert Morris, chairman of the board of directors for the National Commission on Correctional Health Care.

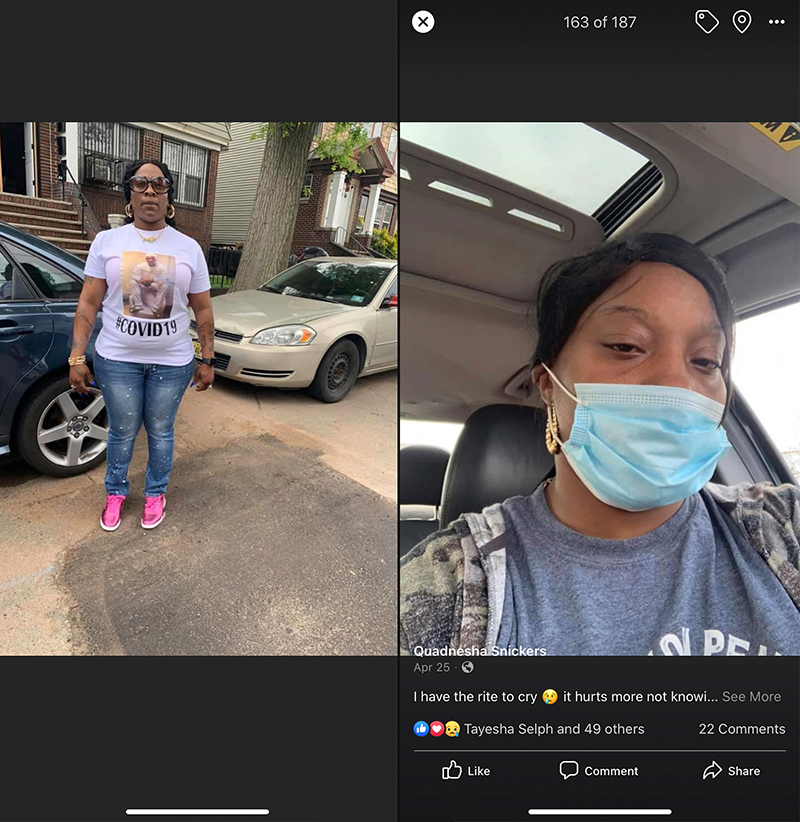

Quadnesha Selph waits every Sunday for a call from her 19-year-old son, Quasim Selph, who has been incarcerated for the past five years at the New Jersey Training School in Monroe Township.

But one Sunday in May came and went without hearing from him. She learned her son was in medical isolation and later tested positive for COVID-19. Quasim, who has asthma, had been sick for about a week.

“I have a right to know as a parent what’s going on with my son. … I should have been notified,” Quadnesha Selph said. “But they didn’t do it.”

Quadnesha Selph video chats with her son, Quasim Selph, who has tested positive for COVID-19 at the New Jersey Training School, where he has been incarcerated for five years. “It’s stressful. It’s hard. It’s sad,” she says. “It’s just a terrible roller coaster ride.” (Photo courtesy of Quadnesha Selph)

In an email to News21, Lisa Coryell, spokesperson for the New Jersey Juvenile Justice Commission, said the state’s practice “is to conduct outreach to parents when a young person is tested for COVID and again when the results are received; outreach to parents upon receipt of results occurs the same day.”

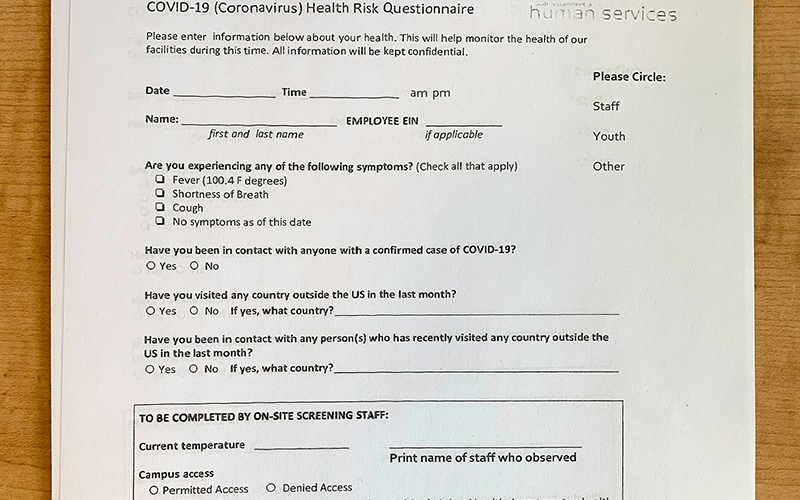

In most states, juvenile detention administrators follow recommendations from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention by reducing family visitation, screening staff and visitors and requiring the use of face masks. As the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 continues to spread, most states are changing procedures to try to slow the spread behind bars, where social distancing and frequent hand-washing is difficult. Some states have decreased the number of youth admitted into detention centers, while others have increased in-home detentions.

In response to growing cases of COVID-19, the Arizona Department of Juvenile Corrections in March mandated face masks, separated incoming youth from the rest of the population for 14 days and suspended in-person visitation, which were replaced by video calls, department spokesperson Kate Howard said in an email.

Medical professionals screened each individual upon arrival at Adobe Mountain School in north Phoenix, the only secure care facility operated by the Arizona Department of Juvenile Corrections, Howard said.

“ADJC has been affected by health issues in the past, including the H1N1 outbreak in 2009-2010,” she said. “However, the impact of COVID-19 is unique. Our response to COVID-19 has evolved and continues to evolve as we learn more about this disease and its spread.”

This spring, Arizona was the site of the nation’s largest COVID-19 outbreak at a child detention and rehabilitation center, according to the Sentencing Project. Yavapai County Community Health Services confirmed the Mingus Mountain Academy in Prescott Valley had 92 cases among its detainees.

The controversy over isolating children

To flatten the curve of infections, children showing symptoms are being placed in quarantine, which advocates and families find troubling. The CDC guidelines recommend placing those with symptoms similar to the coronavirus in medical isolation for 14 days.

This has left thousands of children confined to single cells or locked down in dormitory-style units that typically aren’t equipped for quarantining, said Karen Lindell, senior attorney at Juvenile Law Center in Pennsylvania.

“Young people are being placed in essentially solitary confinement in order in some cases to avoid the spread of the virus,” Lindell said. “But yet the impact on them is going to be the same as if they were placed there for punitive purposes.”

Medical isolation is different from solitary confinement in that children who are quarantined still have access to daily outdoor time, recreational activities, schooling and communication with their loved ones.

Rovner, with the Sentencing Project, and other advocates say misuse of medical isolation could largely contribute to underreporting of symptoms by children who fear they’ll be confined.

Quasim Selph was isolated for a week at the New Jersey Training School before testing positive, his mother said, and he remained in quarantine for an additional two weeks.

“You locking a kid down for 23 hours a day — only one hour out,” Quadnesha Selph said. “That messes with their mind frame.”

Coryell, the New Jersey Juvenile Justice Commission spokesperson, said juveniles in medical isolation are offered time outside their rooms, extra ways to entertain themselves, such as more phone calls, games and books, and can interact with others.

Arjanae Avula, pictured in Virginia, says she mainly worried about her brother’s mental health while he was incarcerated. “I felt scared, but it was mostly uneasy,” she says. “I couldn’t function during the day. I just kept thinking, like I wonder, ‘Is my brother OK.’ I wonder, ‘Is my brother depressed?'” (Portrait taken remotely by Gabriela Szymanowska/News21)

“Youth who test positive for COVID-19 are not isolated alone for 23 hours of the day,” she said.

At Virginia’s Bon Air Juvenile Correctional Center, Waheed Richardson, 18, was put in a cell by himself for 14 days, even though he had not tested positive for COVID-19, said his sister, Arjanae Avula. He told her it felt like punishment rather than protection.

“Our quarantine was based on specific guidance from the Virginia Department of Health to protect the health of residents by ensuring social distancing,” Greg Davy, public information officer of the Department of Juvenile Justice, said in an email. He said a campus-wide quarantine lasting more than two weeks was issued on April 5 after the first positive test result at Bon Air.

Avula said her family found out about the positive cases from a social media post rather than juvenile authorities.

“I was scrolling on social media and I had found out there had been an outbreak in the facility that my brother was at,” she said.

Davy said updates for parents are consistently posted on the Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice’s website, multiple letters were sent out and a virtual meeting was held for parents to ask questions. A notice was posted on the website the day after the first positive test result.

Even before the pandemic, Avula said, communication between Bon Air and the family was not good, but it got worse after. She said she would call, only to be told, “We’ll get someone to call you back” or her call would be forwarded to someone who wasn’t in the office.

Avula said not enough was done to help children detained there, and she worries about her brother’s mental health because of his two weeks in isolation.

In a Louisiana lawsuit filed in May by the Juvenile Law Center, children’s advocates claim a lack of medical oversight, infrequent access to COVID-19 testing, phone calls, family visitation, recreational and learning materials indicates that conditions inside all four state run facilities amount to punitive isolation rather than treatment.

“As a result of the stresses of the pandemic, especially in the early phases, we didn’t have much information. … The kids didn’t know how long they were going to be in this dorm lockdown,” Rachel Gassert, policy director of Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights said in late July.

“They still don’t actually know when they’re going to be able to see their family again.”

Since the lockdown was lifted June 4, detainees and staff members in two Louisiana facilities have tested positive for the virus, leading to new lockdowns. As juvenile facilities resume in-person instruction, vocational training and other services, advocates say they’re confident cases will increase and lead to yet new lockdowns.

Since June, detention centers have resumed in-class instruction and vocational training, but Rachel Gassert, a policy director for Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, says, “It’s impossible to say whether OJJ would have done those things if the lawsuit … hadn’t been filed.”

From riots to brawls to escapes, Gassert said, conditions inside Louisiana juvenile facilities create issues beyond the threat of coronavirus.

“There were a number of serious incidents that resulted in a lot more kids being placed in solitary confinement for punishment,” she said.

In an email to News21, The Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice said they are working closely with their medical provider and the public health department to provide the most appropriate treatment for each youth. The department has established quarantine and isolation guidelines for those exposed to the virus, according to the email.

Elizabeth Touchet-Morgan, spokesperson for the juvenile justice office, said what advocates and local media called “lockdowns” were simply a “quarantine by dormitory.” Youth movement was limited to their own living areas for their health and safety.

Before the pandemic

Before COVID-19 took root across most of the nation, detention centers had drawn criticism for using solitary confinement and other practices that health experts say damage children in lasting ways. The pandemic exacerbated long standing issues within the system.

Children who enter the justice system already are more susceptible to such illnesses as sexually transmitted diseases and tuberculosis, due in part to higher at-risk behaviors involving violence, substance abuse and sexual activity, according to a 2011 report by the Committee on Adolescence of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The report said inadequate health care before children enter the system leads to such undiagnosed illnesses as high blood pressure and diabetes. To help incarcerated youth, the report suggests that detention facilities screen for infectious diseases from unprotected sexual activity, provide comprehensive preventive services and have on-site medical professionals to treat for mental health issues.

“That’s particularly true when you look at young people who have underlying health conditions like asthma or kidney disease or diabetes,” Lindell said. “And these are the kids that are disproportionately in the juvenile justice system, and so we have a vulnerable population there.”

Quasim Selph’s asthma, experts say, puts him more at-risk for COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. Once, his mother said, he had to wait four minutes to get his asthma treatment while nurses checked the temperatures of other children at the center to see if they could be infected. To Quadnesha, these four minutes meant everything.

Quadnesha Selph made shirts to advocate for her son, Quasim Selph, who tested positive for COVID-19 in a New Jersey detention center. The back of the shirt says, “I’m human … treat me as such” and includes many hashtags. “If I could sue them, I would,” she says of the center’s operators. (Photo courtesy of Quadnesha Selph)

Moving forward

Although the pandemic has exposed underlying problems in the juvenile health care system, it has reduced the number of children admitted to detention facilities — something the Annie E. Casey Foundation in Baltimore has advocated for over 30 years.

In detention facilities the foundation surveyed in March and April, the number of children detained before their court hearings had dropped 52%, according to its report “Leading With Race: To Reimagine Youth Justice.”

The reduction, it said, equaled one that took place in a 13-year period from 2005 to 2017, according to the report.

“The Casey position has been that, more often than not, (children) don’t actually need to be in secure detention until their court hearings,” said Tanya Washington, the group’s senior associate.

The Casey foundation and other advocacy groups hope the number of detained juveniles will continue to drop as policies implemented during the pandemic are examined.

“Admissions to juvenile detention centers can stay low if leaders continue to scrutinize detention decisions and to review — if not reconsider — every policy that leans toward confinement,” Washington said. “Unless youth pose an immediate and substantial risk to public safety, the default response should be alternatives to out-of-home placements, including placement at home with terms and conditions.”

Morris, with the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, a nonprofit working to improve standards in correctional facilities, said some youth are placed in detention to receive medical and mental health care — services he hopes will be provided in the community rather than the justice system.

“There is nothing in modern times that anyone who is alive today can come near recognizing as something that’s similar,” Morris said of COVID-19. The most recent comparison Morris could make was the 1918-19 Spanish flu pandemic that killed about 675,000 Americans and 50 million people around the world.

“Systems that have well-run health care are likely to be more resilient to the risk of COVID coming in,” Morris said, speaking for himself and not on behalf of the commission. “However, if you are in a very hot, hot spot (for the virus), that can even overwhelm the best health care systems.”

States like Utah, which had a limited number of youth confined in their 11 state-run facilities because of earlier reforms, were among the least affected. As of mid-August, nine detainees had tested positive for the coronavirus out of 130 youth, said Brett Peterson, director of the state’s Division of Juvenile Justice Services.

The department also allowed 80 youth to serve out their sentences at home, Peterson said, adding that it is the first time the state has more kids serving at home than in facilities.

“We can safely supervise these kids in the community,” he said.

For those still detained, the department added more in-person visitation for youth and increased the number of video calls between youth and family members.

“While we have to keep youth safe during a pandemic, we also have to look at kind of the whole person … their mental health, their physical health, and so that’s why we have to balance these things,” Peterson said.

The Utah Department of Juvenile Justice Services requires staff to fill out a screening form at the Split Mountain Youth Center in Vernal to identify COVID-19 symptoms. (David Green photo courtesy of Jackie Chamberlain/Utah Division of Juvenile Justice Services)

Peterson attributes Utah’s success to the reforms, already having infectious disease protocols in place and an ongoing investment in a robust telehealth program. But moving forward, he said, if there’s a future pandemic, the nation needs to further examine how it’s imprisoning children.

“For juvenile justice specifically, I think this constant conversation of why or when do we place kids into locked settings is the question we need to always keep asking,” Peterson said.

But Gassert and other advocates aren’t sure how the pandemic will change the juvenile justice system.

“As for (Louisiana Office of Juvenile Justice) facilities, I would assume it’s more of the same: testing only symptomatic children, locking down dorms and quarantining youth if there’s a positive test among youth or staff, and continuing to suspend visitation and furloughs,” she said. “However, that is just an assumption based on what they’ve said and done thus far.”

In an email sent to News21, officials from the Office of Juvenile Justice said facilities are continuing to practice social distancing and quarantine guidelines as they resume normal operations. In addition, transports from the facility have been limited to “essential trips” and personal protection equipment has been distributed throughout the facilities.

Lindell, with the Juvenile Law Center, said detention centers, like school districts, operate differently from city to city and facility to facility. Everything from visitation to education programming “is very much in flux,” she said, adding that youth prisons are incompatible with containing disease outbreaks.

“The best way to prepare for a future pandemic is to end our reliance on youth prisons and other institutional placements for youth, and instead invest resources in family- and community-based supports,” Lindell said. “The pandemic has shown that congregate care facilities have structural features that make containing a disease outbreak next to impossible.”

Even though experts are hopeful that lessons from COVID-19 will foster reforms within the system, Quadnesha Selph and other parents are worried about their children right now.

“At the end of the day, these are kids,” she said. “Look at it as if it was your child.”

Delia C. Johnson is a Donald W. Reynolds Foundation fellow, Gretchen Lasso is a Diane Laney Fitzpatrick fellow, and Gabriela Szymanowska is the John and Patty Williams fellow.

This report is part of Kids Imprisoned, a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country. It is headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.