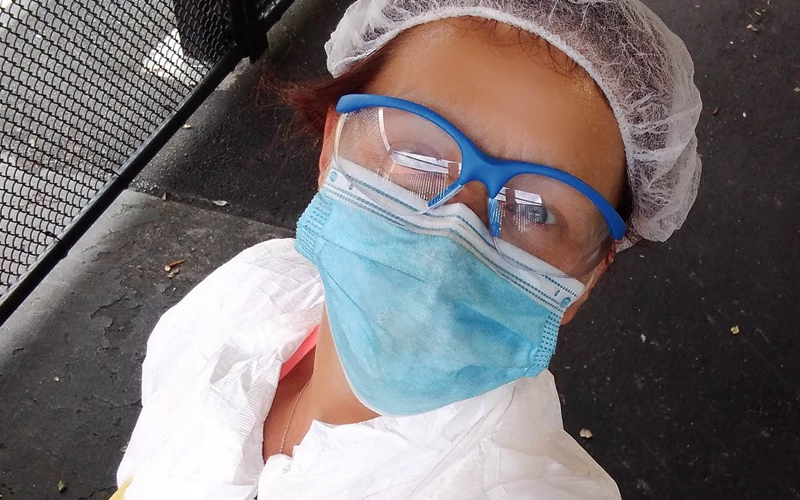

Tiffany Cordaway, 47, as seen in this April 23 selfie, was working two jobs and living in a friend’s car at the start of the pandemic. For her day job, she wears protective gear while disinfecting medical equipment, including some used on COVID-19 patients. At night, she cares for the elderly. (Photo courtesy of Tiffany Cordaway)

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Tiffany Cordaway’s biggest struggle was finding a place to shower. She worked two jobs in Northern California, disinfecting medical equipment during the day and caring for an elderly couple overnight. When she finally clocked out, she just wanted to clean up.

But she had nowhere to do that. Cordaway, 47, was homeless, sleeping in a friend’s car between her two eight-hour shifts. Unlike her co-workers, who talked about showering when they got home, she worried about finding hot water and a place to clean up where no one could see her. Some nights, she just washed from a 2-liter bottle of water.

“I was hearing them talk about how, ‘Oh, I’m going to go home and the first thing I do is walk in the house and, you know, go straight to the shower,'” she said. “And here in the back of my mind I’m thinking, ‘God, I wish I could do that.'”

It’s a common misconception that homeless people are unemployed, but experts say between 25% to 50% of this population works. In the era of COVID-19, that means many homeless employees are working low-wage essential jobs under conditions that put them at risk of catching or spreading the virus.

“Many people wake up in their tent every day, wake up in their vehicle every day, or wake up in their shelter every day and go off to work,” said Dr. Margot Kushel, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and the director of its Center for Vulnerable Populations. “The type of work that (homeless) people do is the type of work that we have seen to be at highest risk because it has been the type of work that you can’t do from home.”

Cordaway said her typical workday at a health care company in Milpitas, California, involves cleaning and sterilizing respiratory equipment, including some used by COVID-19 patients. Even though she wears protective gear, she says she is still afraid of contamination, especially from rubbing against the equipment she uses. Sometimes her clothes get wet and “nasty” while disinfecting the equipment, and Cordaway has to throw them away because, unlike her co-workers, she doesn’t have a washing machine.

“At first, it was kind of scary,” she said. “You’ve got the machines coming in from the people that were breathing on them.”

Despite the danger, Cordaway continued to work her two jobs to save money, noting, “This is a two income world, and I’m only one person.”

She said she worried about exposing her elderly clients to the virus and took precautions, such as spraying her clothes and shoes with the same disinfectant spray she used at work, then changing before reporting for her night shift.

Tiffany Cordaway, 47, as seen in this April 23 selfie, was working two jobs and living in a friend’s car at the start of the pandemic. For her day job disinfecting medical equipment, including some used on COVID-19 patients, she wears protective gear. At night, she cares for an older couple. (Photo courtesy of Tiffany Cordaway)

In May, Cordaway moved out of her friend’s car into a rented room in a house. But the homeowner took in other homeless people who shared common spaces, she said, and she didn’t feel safe there. In early August, she moved into a studio apartment at an extended stay hotel.

“People who are homeless don’t just, like, sit in a shelter, like a defined population,” said Dr. Kelly Doran, a New York City emergency physician whose expertise includes homelessness. “They’re moving out into the world and, you know, risk and potential to transmit the virus kind of goes with them.”

Many who work with homeless communities are reluctant to speak about this risk for fear of further stigmatizing homeless people, even though they do the frontline jobs others avoid.

“We have all been really challenged about how we talk about this because homelessness is so stigmatized and people blame homelessness on the victims of homelessness,” Kushel said. “But let’s be real. If we have outbreaks in shelters, if we have outbreaks in encampments, it doesn’t matter how well we’ve prepared everything else.”

Challenging the stereotype

Collecting data on homeless people who work was inconsistent even before the pandemic.

The last national effort to do so was in 1996. The study, partially funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which oversees homeless programs, found that 44% of homeless people were employed.

HUD requires biennial snapshots of the nation’s homelessness using Point-in-Time Counts done by the housing department’s 400 Continuums of Care, which are local and regional planning bodies that coordinate services for homeless people. Although some Continuums of Care attempt to track employment, they aren’t required to do so.

A review by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism of the recent Point-in-Time reports turned up just 44 jurisdictions that had employment information for homeless people. Of those, the average employment rate was about 19%. This provides just a glimpse of reality; information from about half of the Continuums of Care could not be found.

Even the nation’s top homelessness official seemed unaware of the extent to which homeless people work.

“Our folks are not in the service industry on a regular basis,” Robert Marbut, executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, said in an interview with the Howard Center. “Our people work much more of a gig hourly, cash below the table.”

Adam Cheshire, program administrator for homeless initiatives in San Joaquin County, California, said his county tracks employment because it shows the complexity of homelessness. In 2019, he said, 5% of the 576 homeless people reported an income from employment.

“It illustrates that, you know, homelessness is not just an issue of addiction or just an issue of mental health,” Cheshire said. “It’s also an issue of poverty. And that can be hard for folks to recognize or to understand without having concrete figures to reflect upon.”

The lack of data collected or research conducted on homeless workers also makes it difficult to disprove stereotypes, according to experts, who say poverty and a lack of affordable housing have been root causes of much homelessness, which affects nearly 600,000 Americans.

Kate Duggan, executive director of Family Promise in Bergen County, New Jersey, said better data “would shine a light on the fact that lots of working people become homeless.”

“The stereotype is that homeless people are lazy and drug addicted, and what have you, mentally ill,” she said. “But in fact, many are working, at least part-time.”

Several homeless shelters throughout the country have long served individuals and families who are employed, and in the era of COVID-19 they have taken extra precautions to keep their residents safe.

In New York City, two shelters operated by the Bowery Residents’ Committee, a nonprofit that provides housing and workforce development services to homeless people, moved their working residents from congregate shelters to hotel rooms when the pandemic hit.

In Charlotte, North Carolina, the shelter Roof Above converted an empty dormitory into separate housing in late May for its homeless residents who work. Liz Clasen-Kelly, the organization’s chief executive officer, acknowledged that sharing a bathroom with eight other men was risky, but less so than if they were in the shelter.

“It’s a double risk,” she said. “It would be like if people in nursing homes were also going out to a shopping mall every day.”

Donnie Settles, 27, has worked various jobs in California since becoming homeless two years ago. He was a driver for a towing company and a furniture store, and was working as a hardware store cashier when the pandemic began in March.

“It’s hard to hold down a job being homeless,” Settles said. “And try to maintain the look of not being homeless. And not knowing where your next meal is coming from, and where you’re going to stay the next night.”

At the start of the pandemic, he said he frequented an overnight shelter in Eureka, which provided meals and a shower. But the shelter closed to Settles and anyone else not on the inside when social distancing measures were implemented in late March.

Settles began staying in a hotel room and, when that became too costly, he rented a backpack and tent and slept outside. After five weeks, Settles found a tent shelter erected by the city of Arcata, California, and Arcata House Partnership, to provide socially distanced places to sleep. He stayed there until late June, allowing him to save money for a place to live.

Settles then moved into an apartment after responding to an ad from someone looking for a roommate and started a new job working for a portable toilet provider. Part of his 12-hour-a-day job includes transporting and servicing portable toilets and sinks for homeless people.

Homelessness in many forms

Homelessness looks different in different parts of the country, especially in such agricultural regions as Imperial County, California, which borders Mexico. Homeless people there range from off-the-grid squatters in Slab City – named for the remains of a World War II training base – to migrant workers who tend crops in California and Arizona and Mexican day laborers who cross into the United States. Many are what experts consider “marginally housed” because they either sleep in a car or “couch surf” with friends, or their housing status changes regularly.

HUD’s biennial Point-in-Time count does not consider “marginally housed” people to be homeless. But when researchers in 2013 considered them as part of homeless data from El Paso, Texas, that added about 11% to the homeless roll. They recommended HUD consider counting marginally housed people, who they found were mostly Latino.

Each type of living arrangement carries its own risk of COVID-19 infection.

“We know that specifically for farm workers that many of them live in camps and labor camps or they live in large households with many other farm workers,” said Edward Flores, a sociologist at the University of California, Merced who studied the convergence of poverty, large households and COVID-19 infection rates.

“This issue is not something that’s just afflicting low-wage workers,” Flores told the Howard Center. “It’s also afflicting the people in the households that they live with, because if they contract COVID in the workplace and they come back to a home that has many more people, that has different public health implications than if they had a smaller household size.”

Through much of the summer, Imperial County had the highest rate of COVID-19 infections in California and topped the Howard Center’s list of the 43 most vulnerable counties in terms of infection rate and new infections. Highlighting a pattern of people of color being most affected by the pandemic, Latinos comprised a disproportionate share of infections and deaths. Most of those testing positive were residents of Imperial County, according to data from the county health department.

In his study, Flores found that Imperial and 13 other counties in California with large households of low-wage workers had the highest infection rates. He said the data he analyzed seemed to reflect households with multigenerational families, rather than farm workers living in labor camps or other institutionalized settings.

Unhoused farm workers can be found “sleeping in a car or sleeping under a bridge,” Flores said. “This type of homelessness looks a little bit different than maybe what you find in inner cities.”

At last count, there were more than 1,400 homeless people in Imperial County. But officials said they had no idea how many might be migrant farm workers.

Sergio Gomes Macias, 65, is one such worker. His low-paying job makes it difficult to afford a place to live, so he sleeps on a bench under the palm trees in Calexico, about 500 feet from the border with Mexico. Since nonessential businesses closed amid the spread of COVID-19, it has been hard to find food, water, restrooms and shelter.

Macias said he typically wakes around 2 a.m., when farmworkers gather to be driven to the fields. He listens to people talking across the street to see whether there’s a chance he can find work that day. Despite the pandemic, and the fact that co-workers have died, he continues to work.

“If you are able to shelter in place and work from home, you are very protected from this pandemic,” said Kushel, the national homelessness expert. “Everybody else is very at risk.”

This project was supported by the Pulitzer Center and produced by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication. The Howard Center is an initiative of the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard.

Contact us at [email protected], visit us on Twitter @HowardCenterASU.