PHOENIX – Arizona has failed to conduct robust contact tracing, which was considered a vital tool to slowing the spread of COVID-19 and proved effective in other parts of the world, public health experts say.

And it’s not just Arizona. Contact tracing has “largely failed in the United States” because of long waits for test results and the speed at which the novel coronavirus that causes the disease has spread, the New York Times reported July 31.

Contact tracing allows public health officials to determine how many people were exposed to someone who tested positive for COVID-19, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigative method has been used to successfully control the spread of measles, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases.

Since the novel coronavirus was detected in China late last year, contact tracing has proven effective in reducing the spread of the illness in China, South Korea, Germany and other countries.

“It’s a tried and true method that lowers spread of infectious diseases, and it would be useful for COVID-19 if it’s done right,” said Will Humble, a former director of the Arizona Department of Health Services who now heads the Arizona Public Health Association, which represents health workers and organizations.

For contact tracing to be effective, the patient should be interviewed within 24 hours of testing positive, CDC guidelines say. After the patient identifies where he or she has been and the people with whom they’ve had contact, health officials attempt to reach each of those contacts.

From there, the guidelines recommend, the tracer assigned to the case urges the contact to be tested and follows up every day to offer support services and make referrals to a medical provider if necessary. The exposed person, according to the CDC, should quarantine for 14 days, after which they no longer will be monitored.

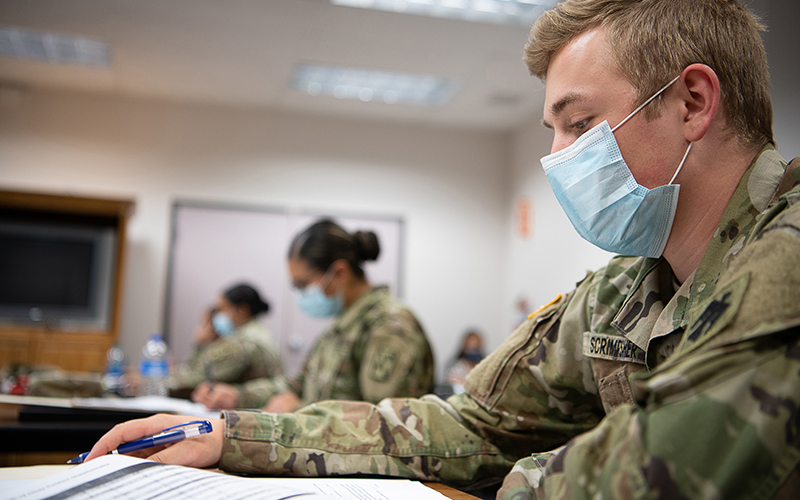

Gov. Doug Ducey on June 17 issued an executive order for the Department of Health Services to “implement a consistent, statewide system for case investigation and contact tracing.” It also authorized using National Guard personnel to trace contacts if needed and called for increased testing.

The contact tracing efforts, introduced in July, are meant to “ensure county public health officers have the support, tools and resources to carry out robust contact tracing,” according to a news release from the governor’s office. Ducey’s office did not respond to Cronkite News’ requests for comment on this story.

But The Arizona Republic reported June 26 that many patients who’d tested positive said they never received a phone call from public health workers in Maricopa County, nor did their contacts. Maricopa is the hardest-hit of Arizona’s 15 counties, with nearly 128,000 cases as of Aug. 13.

Kyle Freese, chief epidemiologist for STCHealth in Phoenix, warned that the state needed to hire 4,000 contact tracers to avoid relying on already overburdened public health workers in a June 5 op-ed in The Arizona Republic. STCHealth has advised federal and international health officials in response to SARS, Hurricane Katrina and other major health events.

But in a July op-ed published in the Phoenix Business Journal, Freese did not recommend more robust contract tracing because “prolonged wait times for test results and inadequate contact tracing efforts compound over time and directly contribute to exponential spread of the virus.”

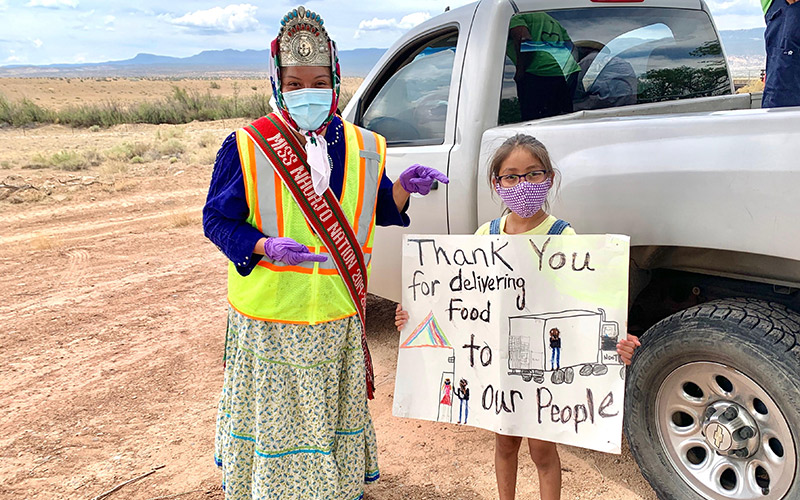

There’s a pocket of eastern Arizona where contact tracing has been effective. A hospital in Whiteriver that serves 18,000 Native Americans on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation expanded contact tracing and used extensive rapid-results testing to protect high risk individuals, according to a July 2 letter in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Despite 1,600 cases of COVID-19 reported in the tight-knit community, where many Apaches live in multigenerational households, the case fatality rate was “1.1%, less than half the rate reported for the rest of Arizona,” the letter said.

Jennifer Franklin, a spokeswoman for Maricopa County, told Cronkite News that county officials reach out to “every positive case we have contact information for, with additional emphasis on high risk cases,” such as patients 65 or older, who are called directly.

“Each case is contacted at least three times through a combination of the following outreach methods: automated phone call, two text messages, a human phone call, and standard mail,” Franklin said in an email.

Roughly 80% of the case investigations are never completed, because there’s a lack of response to the questionnaires.

Weak contact tracing could worsen virus reproduction numbers, known as R₀ values, or “R naught,” Humble said. An R₀ value is the “average number of people who will contract a contagious disease from one person with that disease,” according to Healthline.

If the R₀ value is below 1, the existing infection is reproducing less than one new infection, which would result in the virus eventually dying out.

Ducey more than once has pointed to a R₀ value as a leading statistic in his decisions on reopening the state. During a July 23 news conference, the governor said Arizona’s R₀ value is below 1.

Contact tracing can help continue to reduce the R₀, Humble told Cronkite News.

“It’s a public health practice we’ve done for decades,” he said. “When the R₀ is below 1, the number of cases is slowing down. Contact tracing is a tool to reduce the R₀ but not to measure the R₀.”

The percent of positive COVID-19 cases is used to measure the R₀, Humble said. Arizona is struggling with contact tracing, he said, because the testing turnaround time, which can be up to two weeks, are too slow to track possible exposures accurately.

“The R₀ is an art and a science so it’s not as precise,” he said. “By the time the county health departments get test information, it’s too late to do those investigations because those contacts are most likely already out in the community and have already spread the illness, which negates the purpose of contact tracing.”