Editor’s Note: Coronavirus has devastated Native American communities and put a spotlight on some long-standing problems in Indian Country that have made this pandemic that much worse. But at the grassroots level, everyday heroes have stepped up to help. One in a series.

SCOTTSDALE – Indigenous tribes have their own cultures, languages and customs, but two common threads run through them – high esteem for their elders, and the heavy impact COVID-19 has had on Native communities.

Disparities in elder income, health and overall wellness were not brought on by COVID-19, but the pandemic has shone an unforgiving light on some of the issues elders face.

From Navajos in remote towns like tiny Leupp to the president of the tribal nation, the mission has been clear: Protect the elders.

Defend Our Community

When the pandemic first hit the U.S., Leupp, about an hour’s drive east of Flagstaff, was not a hotspot for infection. But working at Sam’s Club in Flagstaff, Monica Harvey, 37, noticed firsthand how difficult it had become to get essential goods such as toilet paper and food.

Harvey grew concerned for the elders in the Leupp area who, like many of the 174,000 who live on the reservation, often have to travel long distances for supplies and haul their own water to cook, bathe and wash their hands.

Harvey founded Defend Our Community, a grassroots group delivering supplies to elders in need. The organization’s volunteers have helped more than 100 elders and developed countless relationships that will stay with them forever.

“I didn’t want to wait for the numbers to rise,” Harvey said. “We knew what was needed.”

Harvey was joined by Terrah Whitehair, Emmy Slowtalker and others. Together they work tirelessly from Harvey’s home to strategize shopping trips and then sanitize and pack care packages. In the summer heat, the only cooling comes from three fans. Natural light flows in through a single window.

Whitehair and Slowtalker, who also are from the Leupp area, jumped right into the work, gathering supplies and making deliveries.

“We were only going to do a couple,” said Slowtalker, 43. “And then it turned into a need for more and more people.”

The effort evolved by word-of-mouth. Locals started asking for their grandparents or other relatives to be added to the list. Volunteers got names and directions to homes from community members and often asked their own parents to make calls to verify the information was correct.

Although the focus is on Navajos 70 or older, Defend Our Community has made exceptions.

“A lot of our elders on the reservations don’t have reliable transportation,” said Whitehair, 39. “A lot of them are home alone. They’re widowed. Sometimes, it just feels like they’re forgotten.”

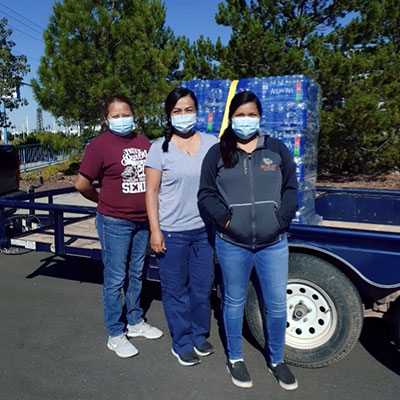

Volunteers with Defend Our Community are, from left, Emmy Slowtalker, Terrah Whitehair and Aimee Hanley. The group is distributing necessities to elders across the sprawling Navajo Nation Reservation. (Photo courtesy of Defend Our Community)

Across the U.S., the 65 or older population increased to 52.4 million in 2018 from 38.8 million in 2008, and it’s projected to reach 94.7 million in 2060, according to the Administration for Community Living. The agency, which includes the Administration on Aging, is a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Likewise, the numbers of elderly American Indians and Alaska Natives also have been increasing. In 2018, according to the Census Bureau, an estimated 290,000 people identifying as Native American alone – or 10.4% of the population – were 65 or older.

Elders, considered the most respected members of Indigenous communities, hold immense cultural wisdom. Because of their age and life experience, they are looked to as pillars of knowledge who pass down traditional teachings to next generations.

But too often, they also need the most aid.

The National Indian Council on Aging reports that twice as many American Indian and Alaska Native elders live below the poverty line compared with the general U.S. population. And 10% of older American Indians need help eating as opposed to 3% of the general population.

In 2017, almost half of older American Indian and Alaska Natives had at least one disability, according to the Administration for Community Living.

Laura Schad, a member of South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and program information coordinator for Partnership With Native Americans, said in an email that these obstacles may make it more difficult to follow safety guidelines related to the pandemic.

“Many elders live in multigenerational households, challenging social distancing recommendations,” Schad said. “Some elders, especially Navajo, live independently in traditional homes. Those lack running water and common utilities … and this, again, complicates the CDC recommendations of frequent hand-washing.”

In part because of these income and health disparities, COVID-19 has hit Native American communities hard. As of Aug. 11, the Navajo Department of Health had reported more than 9,000 cases and more than 470 deaths on the Navajo Nation Reservation.

President Jonathan Nez has been urging Navajos to come together to take care of elders during the pandemic.

“I challenge the Navajo people: Let’s protect them by staying home,” he said during a virtual town hall on June 9. “It’s our responsibility as family members. … I’ve seen some elders, tears running down their face, saying, ‘My kids don’t visit me.'”

The sentiment was echoed by Vice President Myron Lizer, who said that supporting elders during the pandemic and well beyond is beneficial for all.

“Love for our elders means we all win,” he said.

Defend Our Community volunteers ready supplies for distribution to Navajo elders. “Sometimes, it just feels like they’re forgotten,” says Terrah Whitehair, fourth from the left. (Photo courtesy of Defend Our Community)

Looking out for family

The leaders of Defend Our Community have been both heartened and haunted by the elders they’ve met.

During one delivery, Whitehair and Slowtalker approached a trailer home and called out for the man who lived there but got no answer. They found him lying on the ground between some cinder blocks.

Because diabetic ulcers had destroyed the feeling in his feet, the elder had stumbled and couldn’t get up on his own.

Whitehair and Slowtalker got him out of the 102 degree heat, then called his relatives to see whether someone could check on him after they’d left. No one called back.

“It turned up more of an angry side,” Slowtalker recalled. “How can we treat our elders like this? All of these things are running through my head like why, why, why, why, and I didn’t have the answers.”

Members of Defend Our Community, along with some other elders, have taken to keeping watch on the man.

Not all trips are met with sadness. Other deliveries have connected Whitehair, Harvey and Slowtalker with distant family members and helped them forge new bonds.

“At the end of the day,” Harvey said, “we approach as strangers with masks, but … we leave being called granddaughter or daughter or baby.”

“Each elder,” Whitehair said, “has inspired us in a special way.”

For these women, their own relatives served as inspiration for their work.

Harvey’s grandmothers are living, but she’s driven by the thought they easily could have been among those taken by the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

“It just broke my heart to think that could be my grandma,” she said. “And I don’t want to lose her to this invisible enemy that we’re fighting against.”

Added Whitehair: “I think we just kind of forget who our first teachers were, and that was our grandparents. And for me, both my grandparents have passed on. So it’s been kind of like, how do I give back? How do I make my grandparents proud?”

Since moving back to Leupp six years ago, Harvey has been connecting with the community. The pandemic has helped her find a way not only to give back but to build new relationships.

Among her earliest supporters was her manager at Sam’s Club.

“I explained to him what we were doing and that our community isn’t getting any help, and he just told me ‘Stop right there,’ and he reached into his pocket and literally handed me $100,” she said.

She accepted the money, then began to cry.