PHOENIX – In the six months Maria Chávez’s husband has been detained at La Palma Correctional Center, he has been quarantined twice after being exposed to suspected cases of COVID-19.

And quarantine, for him, has meant solitary confinement. Andrés gets 20 minutes a day outside his cell, Chávez said, which he first uses to call his wife of 29 years and family. He uses the remaining time to shower.

“Any normal person would get depressed in quarantine, locked up for almost 24 hours a day,” Chávez said in Spanish. “For those of us on the outside, it’s different. But for the person that’s inside, it’s enough to drive you crazy.”

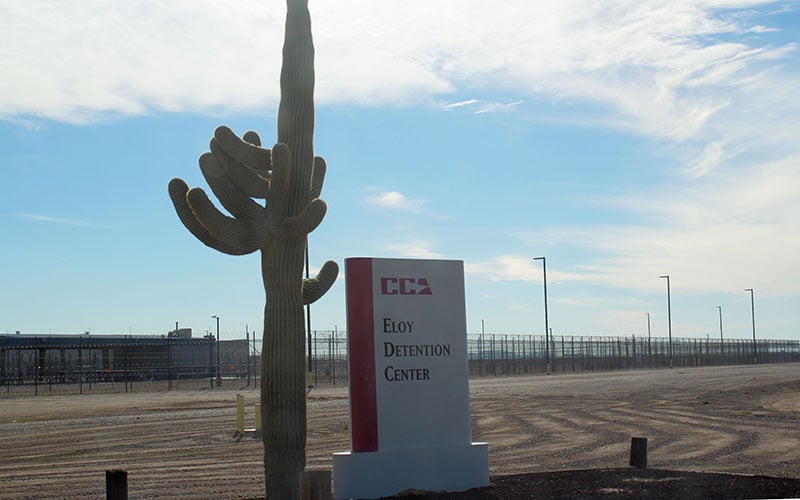

La Palma, which can house up to 3,060 detainees, is one of two privately run Immigration and Customs Enforcement facilities in Eloy, Arizona. The other, Eloy Detention Center, can hold up to 1,456 people.

At the end of July, there were 252 positive COVID-19 cases at Eloy and 108 positive cases in La Palma. Among the roughly 4,000 detainees who had tested positive for the virus as of late July, ICE data showed Eloy Detention Center had the third-highest number of positive cases in the country, after facilities in Washington, D.C., and Texas.

Migrant rights activists suspect official numbers don’t tell the full story — given the lack of comprehensive testing at detention facilities, they say, it’s likely COVID-19 has sickened or infected many more detainees. But officials from ICE and CoreCivic, which owns and operates both Eloy facilities, have defended their handling of the pandemic, saying they’ve relied on federal guidelines to protect employees and “those entrusted to our care.”

Lawsuits filed throughout the country argue those measures have fallen short. Migrant advocacy groups say the facilities’ poor ventilation and small, enclosed spaces put detainees — many of whom are seeking asylum in the United States — at high risk of contracting COVID-19.

They contend release is the “only appropriate remedy.”

Yvette Borja, a border litigation attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, said that if the lawsuits don’t work, “everybody that cares about immigrants is going to need to think creatively about other ways to get folks out.”

“The medical care in both of the facilities has long been documented as subpar,” she said. “If you can’t handle the regular flu, there’s absolutely no way that you can handle coronavirus.”

Advocates allege ‘abysmal’ conditions

Borja said “deadly” conditions at Eloy and La Palma predate the COVID-19 pandemic. “Diseases that we have long had under control” have sickened detainees, she said, citing the 2016-2017 measles outbreak at Eloy.

“The conditions now could only have worsened from an already very abysmal point,” she said.

In June, the ACLU — along with the Florence Project, an Arizona nonprofit that provides free legal and social services to those in detention, and Phoenix law firm Perkins Coie — filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of 13 detainees at Eloy and La Palma.

It’s one of more than 100 such legal challenges filed in the U.S. since mid-March, according to a report published by the Lawfare Institute in cooperation with the Brookings Institution.

In the Eloy lawsuit, attorneys argued that detainees faced “imminent risk, including severe illness or death” in ICE custody. The legal complaint aimed to “build up the fact record and really prove to this judge that the only appropriate remedy for ICE’s constitutional violations is release of these petitioners,” Borja said.

“The conditions of confinement do not allow for social distancing within cells, detainees interact in common spaces, employees move throughout the facility working on multiple units, and detainees are not required to follow recommendations about masks and social distancing in common spaces,” the complaint said.

“Accordingly, as the COVID-19 global pandemic spreads, Petitioners are trapped in a ‘tinderbox scenario’ where rapid outbreak is extremely likely, and extremely likely to lead to deadly results.”

Since the start of the pandemic, LGBTQ migrant-rights organization Trans Queer Pueblo has received three letters from La Palma detainees describing similarly dangerous conditions.

“When we send (a medical) request, it takes four to 15 days for them to come and check us, and they only prescribe us water,” an April 30 letter signed by 32 high-risk detainees says in Spanish. “No matter the illness, they send us to drink water.”

A May 18 letter signed by 29 migrants shared the confusion and frustration of detainees trying to pinpoint where COVID-19 cases existed within the facility.

“From our heart, we ask for help,” the letter said. “We are human beings. We do not want to die here, please.”

Chávez also recalled her husband complaining that officers never provided “explanations or information” about the spread of the virus, even when detainees directly requested it.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainees gather in the yard at the Eloy Detention Center in this 2017 photo. As of Aug. 5, ICE reported 248 detainees at Eloy had tested positive for COVID-19, the third-highest among ICE facilities nationwide. (File photo by Charlene Santiago/Cronkite News)

“He realized what was going on himself,” she said. “There were rumors that people were feeling sick. A few days later, they closed the kitchen. Then a few days after that, he saw that one of the guards was sick — he saw him throwing up in a bag.

“He would hear rumors about, ‘This or that person is sick,’ and then they would put them in quarantine.”

Chávez said Andrés has never felt ill himself, despite being quarantined twice. But it’s impossible to know for sure whether he was ever infected.

He told Chávez detainees have never had access to COVID-19 tests. Officers simply release them from quarantine after 12-14 days if detainees aren’t showing symptoms, she said.

Information ‘slow and inconsistent and filled with holes’

Tom Jawetz, vice president of immigration policy at the Center for American Progress, said the information shared with the public also has been “slow and inconsistent and filled with holes.”

He called the Department of Homeland Security’s ability to provide accurate test rates in ICE facilities “lacking” and said data released by the agency fails to paint a full picture.

“We’ve seen instances of individuals who, once they’ve been transferred to the hospital, have no longer been reported as being in ICE custody, because ICE has essentially released them to the custody of the hospital,” Jawetz said.

He said ICE data on detainee cases doesn’t include those who have tested positive but are no longer in isolation or under monitoring, either.

“There are a lot of problems with how ICE is releasing information regarding these facilities that makes it very hard to even understand exactly what is going on,” he said.

ICE’s COVID-19 page detailing employee cases also appears incomplete and outdated. It shows one confirmed ICE employee case at Eloy — a data point from June that excludes CoreCivic staff members.

Ryan Gustin, a CoreCivic spokesman, said 128 CoreCivic employees at the Eloy facility tested positive for COVID-19 on July 1-2, about 40% of employees there. By July 27, he said, 159 of the center’s roughly 315 employees — about half — had tested positive.

Since then, 139 of those employees have recovered and been cleared for work. At La Palma, 28 CoreCivic staffers have tested positive, and 27 have recovered and received medical clearance, he said.

Gustin dismissed claims about understaffing made by detainees and employees to NBC News last month as “patently false.”

“(Eloy Detention Center) has been staffed appropriately throughout the pandemic,” he said via email. “Part of our COVID-19 comprehensive planning includes contingencies to employ staff from other facilities from around the country with lower COVID-19 impacts to support facilities that may have higher COVID-19 impacts.”

He also said CoreCivic medical personnel are on site 24/7 at La Palma.

Officials: Centers taking health and safety ‘very seriously’

Representatives from both ICE and CoreCivic said they relied on CDC recommendations for cleaning and disinfection to minimize the spread of infection at detention centers.

Those recommendations include disinfecting shared surfaces and equipment; providing soap, paper towels and alcohol-based sanitizer; implementing guidelines for personal protective equipment; and encouraging social distancing.

The facilities also have a “Coronavirus Medical Action Plan” in place that includes isolating high-risk individuals as needed conducting “appropriate testing” with aid from state and local health departments and promoting “regular hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette (coughing or sneezing into a sleeve or tissue), and avoiding touching one’s face,” Gustin said.

Staff and detainees all received two surgical masks in early April, followed by two cloth masks that “may be laundered during weekly laundry exchanges” and replaced upon request, he said. And facilities screen employees for symptoms before they can enter.

“We are fully cooperating with public health authorities and other oversight agencies,” Gustin said via email.

Yasmeen Pitts O’Keefe, an ICE spokeswoman, said the agency takes “the health and safety of its detained population and facility staff very seriously.”

Chávez said her husband’s accounts don’t match that narrative, however.

Early on, he reported making a mask out of the sleeve of his shirt for protection, which a guard confiscated and threw away. She said he received only one mask from officials later, which he has had to use over and over.

She also said Andrés told her it seemed detention officers had disregarded several health and safety rules in recent weeks.

“My husband told me it’s clear the guards don’t care anymore, because they don’t even wear masks anymore,” she said. “He said, ‘There’s a holding cell with a bunch of infected (detainees) — guards go to that cell and then come to ours. They could infect us.'”

Chávez said she has felt “the same worry, desperation day and night” since the day Andrés was detained more than six months ago.

In some ways, it’s even worse now, she said: Before the pandemic, their children could visit Andrés and at least let her know he looked OK.

“Since they got rid of visitation, they haven’t been able to see him, and my worrying has gotten worse,” she said. “The anxiety is huge.”

This story is made possible through a partnership between the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University, with the support of the Henry Luce Foundation.