PHOENIX – By now, you’ve probably heard it more times than you can count: One of the simplest ways to reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection is to wash your hands.

But for the nearly one in three Navajo Nation households without indoor plumbing, that’s easier said than done.

“People (here) call it a luxury to be able to have running water,” said Yolanda Tso, a Navajo Nation member and community advocate. “I don’t really believe that should be considered a luxury in this day and age, especially in this country.”

Tso founded WATERED – Water Acquisition Team for Every Resident & Every Diné – to help fill gaps in water access on the reservation, which this summer eclipsed New York in per-capita coronavirus infection rates, according to CNN. She started raising funds to purchase hand-washing stations for families in need in April and began deliveries in June.

Tso said she knows her small-scale, donation-dependent operation can’t fix the broader infrastructure problems on Navajo land. In 2018, the Indian Health Service told Congress the tribe had more than $450 million in unfunded water needs.

But she hopes it can help even the playing field for a population infectious disease specialists say has a higher-than-average risk of contracting COVID-19.

“At this moment, it’s going to help people be able to accomplish those goals of protecting themselves,” Tso said.

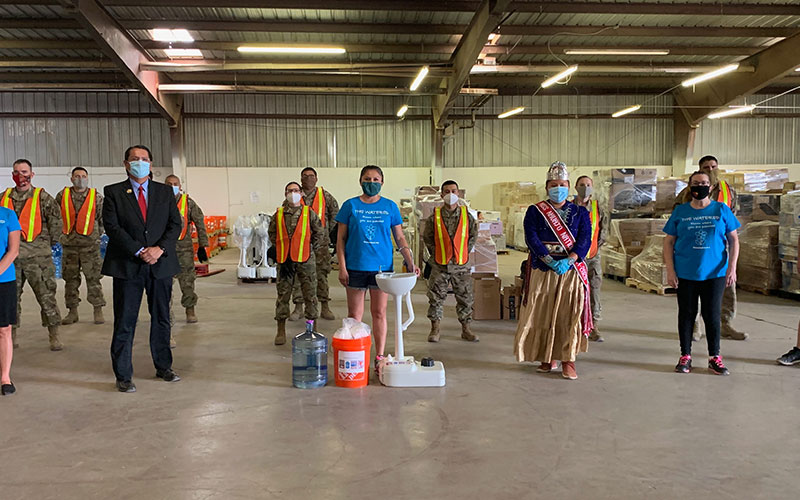

Yolanda Tso (in blue) and volunteers unload hand-washing stations from a delivery truck donated by the moving company State 48. (Photo courtesy of Yolanda Tso)

Impact of federal relief funding unclear

As of Aug. 4, the Navajo Health Department had reported 9,156 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in a population of about 175,000 – more infections per 100,000 residents than any state in the country, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

The reservation also had a death toll higher than that of 16 U.S. states, with 463 residents lost to the disease by that date.

Navajo officials have proposed spending about $300 million of the $714 million they’ve received in federal CARES Act funding on water infrastructure to help slow the spread of COVID-19, according to a release from Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez’s office.

But restrictions require officials to spend CARES Act funds by the end of the calendar year, and Navajo officials say it likely would take at least two years to get a substantial water infrastructure project off the ground.

Even if the federal government grants the spending extension Navajo leaders have requested, the extra time would not address the immediate needs of families without running water.

That’s where Tso and other Navajo volunteers come in.

WATERED’s team has delivered hand-washing stations to more than 110 households on the 27,000-square-mile reservation as a stopgap measure, Tso said.

The stations include reusable 5-gallon jugs and 5-gallon buckets for catching used water, and WATERED provides liquid hand soap, toilet paper, paper towels and disinfectant.

The group relies on donations to cover supply and travel costs, Tso said, and some local companies have made in-kind contributions to increase WATERED’s efficiency and reach. The Glendale moving company State 48, for instance, provided a delivery truck to transport of the stations.

These families “don’t have the ability to get a main source of stopping the spread of COVID as easily as most other communities,” State 48 owner Amanda Lindsey said.

Yolanda Tso, founder of the WATERED, demonstrates how to use the hand-washing stations provided by the organization. (Photo courtesy of Yolanda Tso)

Pandemic prompts ‘important’ access conversation

Annie Lascoe of DigDeep, a nonprofit that works to address water needs on the reservation and elsewhere, described water access as a “deeply entrenched racial justice issue.”

White households are 19 times as likely as Native households to have running water, according to a 2019 report from DigDeep and the Water Alliance that argued rural and tribal community members “understand the historical barriers to access better than outsiders.”

“When we’re looking at Indigenous peoples’ rights, Indigenous communities around the world are the ones that are preserving all of our natural resources,” Lascoe said, citing the Navajo philosophy of “tó éí ííná” – “water is life.”

Yet Native populations are “the No. 1 communities that are also deeply impacted by entrenched systems that have robbed them of access to those resources,” she said.

Indeed, the U.S. government has repeatedly left tribal officials out of key water-policy negotiations, despite the 1908 Winters Doctrine promising federally reserved water rights to Indigenous communities.

Navajo leaders in recent years have pursued water settlements at the state level in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico, but the Navajo Department of Water Resources continues to point to a “lack of adequate domestic and municipal water” as one of the nation’s biggest challenges.

Tso said she would “would never choose a pandemic to have these conversations,” but “it’s so important for people to understand that even though we live in 2020 and we think of America as this superpower, we still have people who are living in conditions that are subpar.”

“We have to be able to lift each other up,” she said. “That’s the only way we’re going to make it out of this together.”

This story is made possible through a partnership between the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University, with the support of the Henry Luce Foundation.