Today, the Latino and Hispanic population is the largest ethnic or racial minority group in the country, according to the U.S. Census. Yet, experts say their presence in the juvenile justice system is severely underreported.

Many experts agree Latino, Indigenous and Hispanic youth are misidentified and poorly counted in county, state and national statistics due to inconsistencies in definitions, categories or even having the option to self-identify at all.

“We’re basically invisible,” said Marcia Rincon-Gallardo, director and founder of Noxtin and executive director of the Alianza for Youth Justice. Both organizations focus on the disproportionate impact of the juvenile justice system on Latino youth, families and communities.

Hispanic youth are disproportionately represented in the justice system, according to existing statistics from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Hispanic youth are detained at nearly twice the rate of white youth and are committed to court-ordered placement 30% more often than white youth.

In certain states, the disparity is significantly worse than the national average.

For example, in Utah, Montana and Pennsylvania, Latino youth are more than three times as likely to be held in placement than white youth, and in Massachusetts more than seven times as likely, according to The Sentencing Project, based in Washington, D.C.

Rincon-Gallardo said there also are inconsistencies among legal institutions such as police, courts and correctional facilities.

“Each one of those institutions counts Latinos a particular way, and sometimes it’s apples and oranges to try to aggregate it,” Rincon-Gallardo said. “What we found are incredible inconsistencies even in the 11 most-populated Latino states, and so we’re very concerned.”

Data on race and ethnicity reporting from states as a whole are decreasing, said Melissa Sickmund, director of the National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Sickmund said that in the past, the federal government encouraged states to track and report racial and ethnic data to receive funding. Recently, that has begun to change as funding to states’ juvenile justice departments shrinks, making it more expensive to abide by the grant requirements than to just not record the data at all.

“Because the money available to states for juvenile justice has gotten really low, a number of states have or are considering no longer playing the (government’s) game,” Sickmund said.

The result of this is less reliable data on a state and county level, Sickmund said. She often asks state justice departments to “please report the data,” or the data published on sites such as the OJJDP’s will be largely theoretical.

“They’ve dropped out of asking for the money, and the quality of some of the data has really diminished,” Sickmund said. “It’s kind of becoming a problem.”

Already most states’ systems do not record ethnicity but also do not have an option to identify as Latino or Hispanic, resulting in Hispanic youth being counted as “white,” according to a report from The Sentencing Project.

The terminology in research and data collection use is important as well, Rincon-Gallardo said.

The term Hispanic refers to persons who are from or have ancestors from a Spanish-speaking country, which does not include all countries in Latin America, and also refers to countries such as Spain and Equatorial Guinea. The word Latino refers to those who are from Latin American descent, which includes non-Spanish-speaking countries such as Brazil.

Not all Hispanic people are Latino and not all Latinos are Hispanic, according to a report from the University of Connecticut School of Law. Hispanic is the term most often used in data, according to the Urban Institute.

Another term being used recently, Rincon-Gallardo said, is L.I.P.O.C., or Latino Indigenous Persons of Color.

Many Hispanic and Latino people also identify themselves as Indigenous, meaning their family comes from colonized countries in Central and South America but have ancestry tied to the Indigenous populations that lived there prior to the Europeans.

As most Latino or Hispanic youth have multiple identities, without accurate data collection methods, advocacy groups say the disproportionate impact on these communities is hidden.

Many Latinos identify as mixed race, Indigenous or Afro-Latino. Hispanic or Latino ethnic identities can be split further by country of origin, according to a report from the Urban Institute.

Joshua Rovner, a senior associate at The Sentencing Project, analyzes racial disparities in the juvenile justice system. He found the lack of data and of consistency problematic, he said.

“(In the data) if you are Latino, then you cannot be African American,” Rovner said. “The fact that the data is aggregated or disaggregated but also just grouped in a way that each kid only gets one ethnicity, well half of Native youth in this country are also Latino, but they get categorized as one or the other.”

Tanya Washington, a senior associate for the Juvenile Justice Strategy Group at the Baltimore-based Annie E. Casey Foundation, has found it challenging to collect data and rates of incarceration for Latino youth in her work, she said.

“There may be one state that has state data that’s required and all the locals collect it, and then there’s another state where only certain types of data are collected at the state level, and then the local levels have all their own unique way of doing things,” Washington said.

During her time as a strategic consultant in Georgia, Washington said the local levels of the juvenile justice system all had their own system of collecting data on race and ethnicity and “didn’t talk to each other,” which made the work very complicated.

Rincon-Gallardo said the demographics of race, ethnicity, gender, geography, sexual orientation and gender expression should be collected and publicly available throughout the juvenile justice system.

Without being counted properly, she said, the justice system does not have an accurate idea of the size of the population incarcerated. More importantly, Latino communities across the country will not receive the funding they need to support alternative, solution-based programs for their youth.

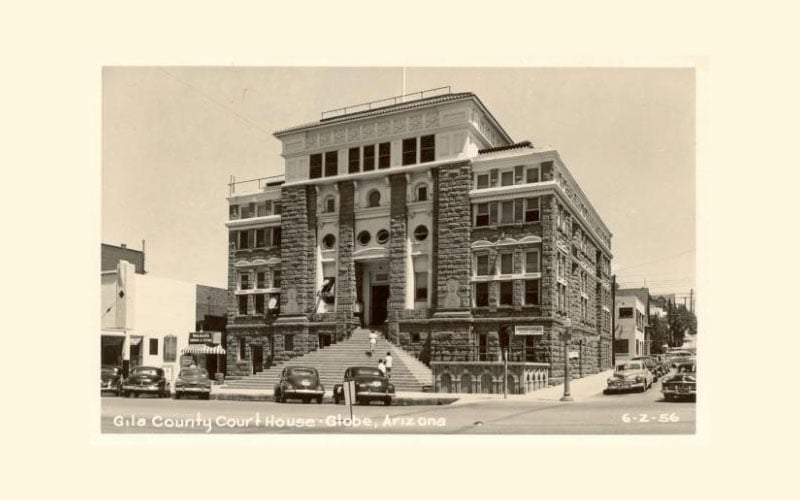

Funding for reform programs often comes from data showing a disproportionate issue within the community. In states such as Arizona or California with more Latino communities than other states, without accurate information, it can be difficult to understand the true scope of the issue.

“We hear so often of the need for good data, of the need for proven programs,” Rovner said. “The way that you prove that a program is working or understand the scope of a problem is to measure it. You can’t have a solution without measuring the scope of the problem.”

Organizations such as the W. Haywood Burns Institute, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Alianza and The Sentencing Project are working to bring attention to this issue – but without the mandated and public data collection for funding, analyzing the problems in their community and identifying the means to solve them proves challenging, Rincon-Gallardo said.

“We felt that until we get counted and have the data that we cannot hold systems accountable, not only to respond with customized approaches, but also to decrease and to end incarceration for Latinos in the same way that we’re looking to end incarceration for all youth,” Rincon-Gallardo said.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Walter Cronkite School-based Carnegie-Knight News21 “Kids Imprisoned” national reporting project scheduled for publication in August. Check out the project’s blog here.