Cardiopulmonary resuscitation training, like this, is often not widely available in Spanish, just one of the reasons that the life-saving first-aid procedure is less likely to be administered by bystanders in Hispanic communities, a recent report says. (Photo by Truckee Meadows Community College/Creative Commons)

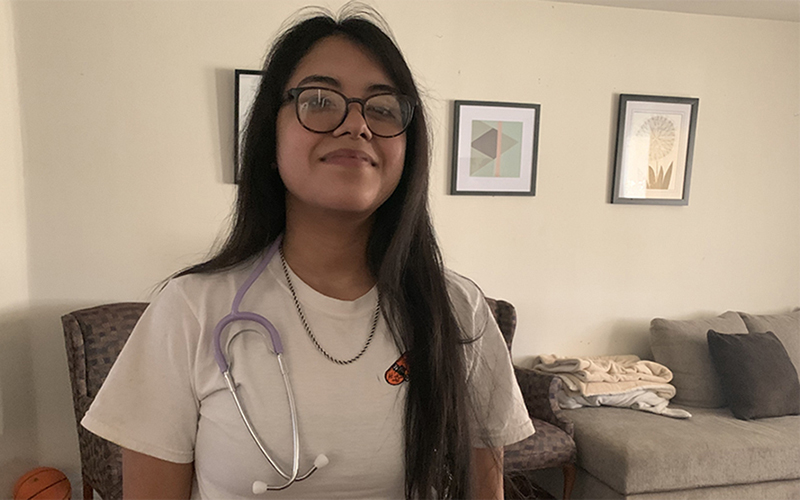

Maryvale resident Jennifer Pastrana, at home with her mother, Rosa, worries that a lack of training in Hispanic communities for CPR could mean that people will not be ready to respond if a friend or family member has a potentially life-threatening medical event. (Photo by Concettina Giuliano/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Jennifer Pastrana calls her mom a traditional Hispanic mother, working multiple jobs to provide for her family and save some money, and leaving little time for visits to the doctor – much less CPR training.

But it’s not just Pastrana’s mom.

A study last year found bystander CPR – given, as the name suggests, by a bystander when someone suffers a heart attack – is less common in neighborhoods that are primarily Hispanic, and that chances of surviving a cardiac arrest in those neighborhoods are low.

That situation is made more complicated by a reluctance by residents of Hispanic neighborhoods to call 911, according to another study, a call that could bring help to someone in need of CPR or could walk a bystander through the procedure.

Pastrana, a Maryvale resident who is studying to become a phlebotomist, learned CPR as part of her studies. She gives family members a monthly checkup. But worries about what the lack of training could mean in the community.

“They could have heart disease or lung issues — and one day, God forbid, they could start going into cardiac arrest and you start performing CPR, which could potentially save their life,” she said.

CPR, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, is a first-aid technique that helps keep blood flowing when a person’s heart stops beating, by manually pressing on the person’s chest.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that if CPR is performed in the first few minutes of cardiac arrest, it can double or triple a person’s chances of survival. Without it, death can occur in minutes.

-Cronkite News video by Concettina Giuliano

The CDC says about 350,000 cardiac arrests happen outside a hospital or health care facility each year, and that about half the victims do not receive the care they need until an ambulance arrives.

The problem of inadequate care is particularly pronounced in Hispanic neighborhoods, according to the study published Dec. 30 in the American Heart Association’s journal, Circulation.

The study of almost 19,000 heart attacks from 2011-2015 found that victims in neighborhoods that were less than 25% Hispanic were likely to receive bystander CPR in 39% of the cases, but that aid was rendered just 27% of the time in communities that were more than 75% Hispanic. The study also found that survival rates dropped accordingly.

Some groups are looking to change that.

“Here, the American Heart Association is providing free CPR classes in Spanish, which I think is the first step in really engaging the community,” said Dr. Rachel Bond, a board member for the American Heart Association.

The Heart Association offers a number of CPR guides and resources in Spanish, and the Arizona Department of Health Services is working to help spread the word about the value of CPR and heart health. And a group of University of Arizona medical students is creating training videos, in Spanish and English, about hands-only CPR.

The health department has also developed the Save Hearts in Arizona Registry and Education (SHARE) program that aims to educate the public on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest care. Bond said officials are beginning to emphasize the need to perform compression-only CPR – without mouth-to-mouth resuscitation – outside the hospital.

“The vast majority of cases that occur outside of the hospital, about 80%, are because the heart just stops pumping,” Bond said. “We don’t have to perform rescue breathing. What we can do is hands only.”

But even in the most-responsive neighborhood, not everyone knows CPR. The overall rate in the 2019 study of bystander CPR was just 37%. That’s where a call to 911 can help but, here again, Hispanic neighborhoods are at a disadvantage.

A 2015 study of Hispanic neighborhoods in Denver, also cited in the Circuiation article, found barriers to calling 911 for residents of those neighborhoods. Among the issues that kept them from calling for emergency help were a distrust of law enforcement, the bystander’s immigration status and language issues.

Jennifer Pastrana, a Spanish speaking Phoenix resident who is studying phlebotomy, tries to engage parents in her push to increase awarness of and training for CPR in Hispanics communities. (Photo by Concettina Giuliano/Cronkite News)

“So with that first simple step of calling 911 there may be a fear, especially now with people’s immigration statuses being called into question,” Bond said.

For Pastrana and her family, busy lives and a lack of resources in Spanish keep them from learning CPR. She knows CPR is extremely important for people to learn and it’s a simple process, but feels there is not a lot of information about CPR in her community.

“In communities like this one not a lot of people post about it,” Pastrana said. “In more suburban areas, there’s no barrier to English and people have more opportunity to go to certain places and people know more people.”

Pastrana said one of the biggest ways to help the community learn about CPR is to engage the parents.

“We should find resources to help parents, especially our parents,” Pastrana said. “Like say ‘hey mom, dad, aunt, uncle, if you see this you should go learn it’ because you never know what can happen to your grandpa, grandma or even baby.”