WASHINGTON – A surge in COVID-19 patients could overwhelm Arizona hospitals in the coming months if action is not taken now to expand hospital capacity and curb infections, according to a new study by the Harvard Global Health Institute.

And the state is not alone.

The study, published Tuesday with ProPublica and the New York Times, says American hospitals face a daunting future that other parts of the world have seen, said one of the report’s authors.

“Without seeing the numbers, the risk seems theoretical,” said Thomas Tsai, a surgeon and one of the project leads at Harvard. “But looking at the numbers it really breaks through the notion that somehow we’re different from the rest of the world.”

Arizona health experts said they are well aware of the potential danger and doing all they can to prepare. But they also warned that the numbers in the report “paint a worst-case scenario” and worry it will cause more alarm than necessary.

“It’s something that we need to take with caution because if you look at their modeling, the way they did the numbers, it’s based on assumptions that may or may not happen,” said Holly Ward, a spokeswoman for the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association.

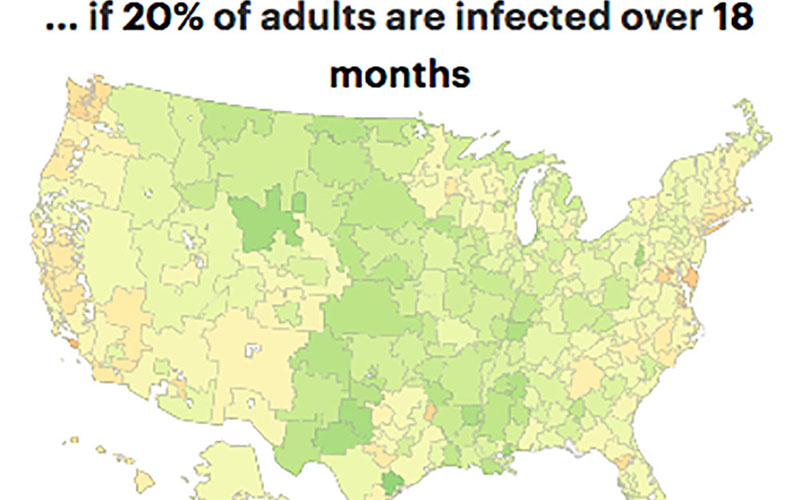

Most U.S. hospitals could handle COVID-19 if just 20% of adults were infected over 18 months, a new report says. Dark green is zero and yellow is 100% capacity on the map. (Map by ProPublica, based on Harvard Global Health Institute, Hospital Bed Capacity & COVID Estimates)

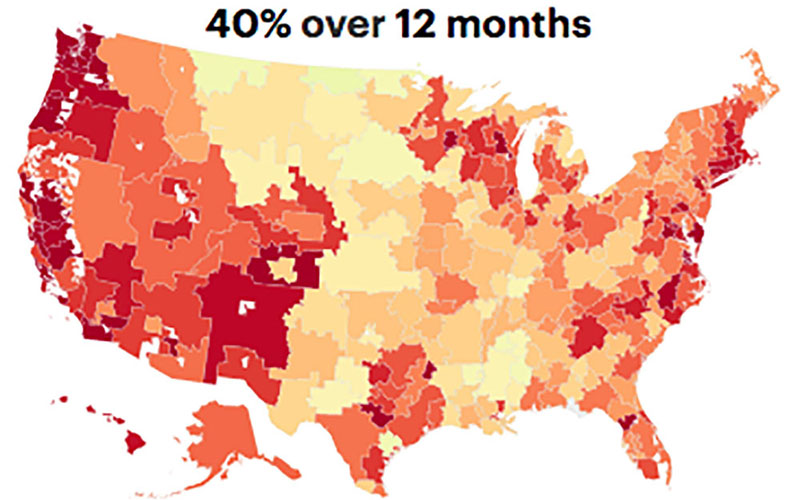

At the midrange scenario in the report, with 40% of adults infected with COVID-19 over a year, all of Arizona’s hospitals would be overwhelmed. (Map by ProPublica, based on Harvard Global Health Institute, Hospital Bed Capacity & COVID Estimates)

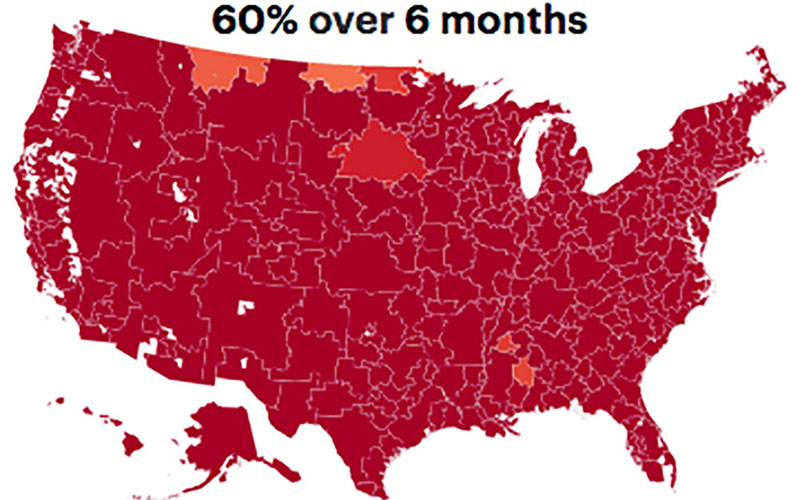

In the most dire scenario in the Harvard study, with 60% of adults infected over just six months, hospitals would be overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases. Dark red is 200% of bed capacity. (Map by ProPublica, based on Harvard Global Health Institute, Hospital Bed Capacity & COVID Estimates)

The report looked at the average number of available hospital beds in each of 305 designated hospital “referral regions” in the country. It compared that with the number of patients that could be expected to flood hospitals under nine scenarios: When 20%, 40% or 60% of adults were infected with the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 over a span of six, 12 or 18 months.

In most of the scenarios, the report said, “the sheer number of patients at risk for COVID-19 may overwhelm the system if preparations are not taken.”

Arizona has four such regions, the largest being Phoenix and Tucson, which respectively have 2,567 and 1,184 hospital beds available on average. The two smallest, Mesa and Sun City, average 648 and 364 unoccupied beds.

In all but the most mild scenarios, capacity in each of Arizona’s four regions was quickly reached or exceeded. In more dire predictions, hospitals would end up with just a fraction of the beds needed to treat the influx of patients.

If, for example, 40% of the population got sick over six months, the Mesa-Chandler region would need to increase its capacity by 971%, the report said. The Phoenix region, which stretches to include Flagstaff and Yuma, would need to increase its beds by 598%.

Mark Coleman, a registered nurse in Phoenix, said as the number of novel coronavirus patients increases, he fears shortages of beds and other supplies will lead Arizona to experience issues similar to what New York is facing.

“They are quickly running out of ventilators and attaching multiple people to a single ventilator,” he said of New York hospitals. “We could probably look forward to that in the near future when there is a surge.”

But state hospitals said they are actively planning for the oncoming waves of cases and working with local and state governments to prepare.

“Hospitals prepare every day, every month, every year for emergency preparedness,” Ward said. “This is not new to Arizona hospitals.”

Daniel Derksen, a University of Arizona professor of public health, agreed with Ward that the numbers in the report need to be considered carefully, pointing to the many unknowns with COVID-19, partially due to the lack of testing and slow results in the U.S. He said in an email that studies such as Harvard’s “can paint a worse-case scenario that alarms a lay public.”

“Until we get the testing kits more widely available and the more rapid turnaround of those results it’s hard to really comment on how reflective this would be in the near or longer term for our state or for our country,” Derksen said in a telephone interview. “The math can get pretty complicated, and the further you get down into the subsets on a set of assumptions I think the less certain you can be.”

Tsai recognizes that his study paints an extreme scenario but said it’s important information for doctors and decision makers to understand the gravity of the pandemic.

“I think there’s still room for optimism, and the goal of putting our data out into the public sphere is to not incite panic but to instill collective action,” Tsai said.

Derksen agreed that whether the report reflects “reality or not, I think in a pandemic it’s always better to prepare for the worst case scenario.”

Experts agree that the best strategy to battle the pandemic is twofold. The first step is to slow the rate of infections through such practices as social distancing and frequent hand-washing to “flatten the curve” in the growth of confirmed cases. The second is to increase hospital capacity.

But Tsai said you can’t do one strategy without the other.

“The importance of the ‘flatten the curve’ concept is that it basically buys time for the second approach, which is, hospitals increase the capacity of their hospital beds,” Tsai said.

That’s easier said than done, Coleman said.

“There’s a lot of regulation infrastructure behind opening up a hospital room,” he said. “I wish it were as simple as slapping a cot on the floor.”

Despite the obstacles, Coleman said he was optimistic that with the government assistance, hospitals and healthcare workers would be ready to meet the challenge.

“We have to be; there’s not another choice right now,” he said.