COLLEGE STATION, Texas – Responding to a steep rise in reports of hate crimes on campus, at least 260 colleges and universities have implemented bias-response teams or other reporting policies to track such incidents. But the teams have created friction of their own, as conservative students, controversial speakers and followers of the alt-right movement claim colleges are sanitizing campuses of dissent, in violation of the First Amendment’s right to free speech.

According to data collected from 6,506 higher education institutions by the U.S. Department of Education, the number of reported campus hate incidents increased from 74 in 2006 to 1,300 in 2016. Vandalism and intimidation account for 76 percent of incidents.

Some of these incidents have drawn national attention, such as a swastika drawn in feces at University of Missouri in 2015; bananas marked with the name of a black sorority, and hung by nooses at American University; and the 2017 Unite the Right rally at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, which claimed one life.

In October 2017, at the University of West Florida, anti-LGBTQ fliers were posted that stated homosexual parents abuse their children and carry diseases. In April, two Jewish students were derided with anti-Semitic phrases and one was assaulted at Towson University in Maryland.

Such incidents are prompting many institutes of higher learning to reshape campus safety and diversity programs.

Universities with bias-response teams allow campus community members to file reports after experiencing hate or bias, often through online forms or by phone. Many teams only keep records of the reports, but others conduct investigations and hold meetings with victims and perpetrators. These teams are largely comprised of campus law enforcement, administrators and faculty, according to a 2017 report by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), a legal advocacy group focused on speech rights at colleges and universities.

The bias-response system “lets you know you have an advocate on your side,” said

Adan Raed Abu-Hakmeh, a Palestinian Muslim immigrant who experienced what she called “casual racism” at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. “It (the response system) takes away some of the emotional turmoil.”

But universities are left to negotiate a fine line – sometimes in court – between upholding free speech and preventing hate speech, putting them in a difficult position, said Adam Steinbaugh, author of the FIRE report.

“When people hear ‘bias-response team,’ they tend to hear something Orwellian,” he said. “Students do have real issues that can be hard to deal with, but the university has to know when they say ‘We want to hear your concerns,’ they can not follow it up with punishment of speech.”

In 2016, the University of Northern Colorado terminated its bias-response team after a professor was barred from discussing transgender issues in class and a student was asked to remove a Confederate flag from his dorm window.

Central Michigan University also disbanded its team in 2017 after FIRE sent them a letter regarding the constitutionality of their bias policies.

The University of Iowa canceled plans to form a bias-response team in 2016, pointing to Northern Colorado as a primary reason. Instead, a year later, it formed a Campus Inclusion Team which provides students resources, such as how to make a formal complaint. However, it cannot investigate complaints, or hand down discipline or punishment.

Georgina Dodge, former University of Iowa chief diversity officer, said officials at Iowa bypassed the formal bias-response team approach for a sounding-board method.

The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor also came under fire in May after Speech First, a legal advocacy group, sued the university over its bias-response team. This is the first lawsuit filed by Speech First, a membership association created to protect college students’ right to free speech.

Nicole Neily, Speech First president and CEO, said bias-response teams are “fundamentally un-American and have no place on college campuses,” in a statement announcing the lawsuit.

In June, the Department of Justice filed a statement of interest in the case, agreeing that “the University’s Bias Response Policy chills protected speech.”

University of Michigan officials declined to comment on the lawsuit, but in an op-ed published in The Detroit News, UM president Mark Schlissel defended the bias-response team, stating the suit “paints a false caricature” of the university’s commitment to free speech. Schlissel said the team does not have the authority to investigate or issue punishments.

“UM’s Bias Response Team, is first and foremost, a support resource for students who come to UM to learn,” Schlissel wrote. “It refers students who experience bias to other campus resources as appropriate, and educates the university community about issues related to bias.”

The University of Michigan’s bias-response team was targeted in a lawsuit filed in May by Speech First, a membership association created to protect college students’ right to free speech. (Photo by Jim Tuttle/News21)

Speech First contends the bias-response team hinders conservative speech. In the suit, 10 anonymous UM students said their political views made them targets of verbal and physical attacks motivated by bias.

One wrote, “I wear my hat with Trump’s slogan on it ‘Make America Great Again’, around campus and I might as well be in full (Ku Klux Klan) ensemble judging by how I am treated.”

Joseph Russomanno, associate professor and First Amendment expert at Arizona State University, has noticed a political flip-flop regarding free speech in recent years. Conservatives, who used to largely reject free speech, now embrace it to defend their right to express themselves, Russomanno said, while liberals are trying to silence others, especially involving diversity, race or religious issues.

“The irony is that when you try to shut down speakers, you are throwing a pie in the face of one of the foundational liberal values that exist in democracy,” he said.

Dylan Berger, president of UM College Republicans, said mainstream conservatives on the Michigan campus don’t think they can state their beliefs without fear of recourse.

“I shared a conservative viewpoint in class once and nobody agreed with me, which is fine,” Berger said. “But then after class I had people come up and pat me on the back and quietly tell me they were on my side, but they didn’t feel like they could say it in class.”

The role of the university, he said, is not to “coddle” students but to facilitate learning. UM should only take action on speech when it proposes violence, Berger said, not when it simply makes people uncomfortable.

Critics of bias-response teams usually miss the point of why these teams exist, said Ryan Miller, assistant professor at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, co-author of the 2017 article “Free Speech Tensions: Responding to Bias on College and University Campuses.”

“They are creating a mechanism for universities to be aware of their own campus climate,” he said. “Universities with these teams are able to support victims of bias they may have otherwise not known about.”

Shawnboda Mead, bias-response team co-chair at the University of Mississippi in Oxford, said bias-reporting policies are becoming a best practice in higher education.

“We are not here to police speech,” she said. “We are here to be educational and to explain the difference between someone not liking speech and speech creating a hostile environment, while always balancing the rights of everyone involved.”

The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the decision to protect offensive speech in at least three campus-specific cases. Now, public universities are facing criticism for past punishments of hate speech.

Past punishments, future problems

On March 7, 2015, members of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity chapter at the University of Oklahoma took a charter bus to a Founder’s Day formal. Dressed in tuxedos and accompanied by dates, they began chanting, “There will never be a (N-word) in SAE. You can hang him from a tree, but he will never sign with me.”

The next day, a black student group, OU Unheard, received an anonymous message with a nine-second video of the chant. Unheard tweeted the video and it went viral. Within 48 hours, former OU President David Boren disbanded the fraternity. Greek letters were removed from its house and members were booted from the property.

Boren expelled Levi Pettit and Parker Rice for their “leadership role” in the chanting.

In response to the video, Unheard led an early-morning demonstration on the steps of the campus administration building. Former Unheard member Everett Brown recalled an “ominous feeling in the air” that morning.

“Close to 1,000 people were crowded on the North Oval. It was pitch black and silent,” Brown said. “After President Boren came out of the building to speak, the sun started to come up. We passed out some sticky notes for people to write down their issues with the university. Some people were taking rolls of tape and putting it over their mouth to symbolize the voices unheard. Then we all walked to the student affairs office and placed the notes on their door.”

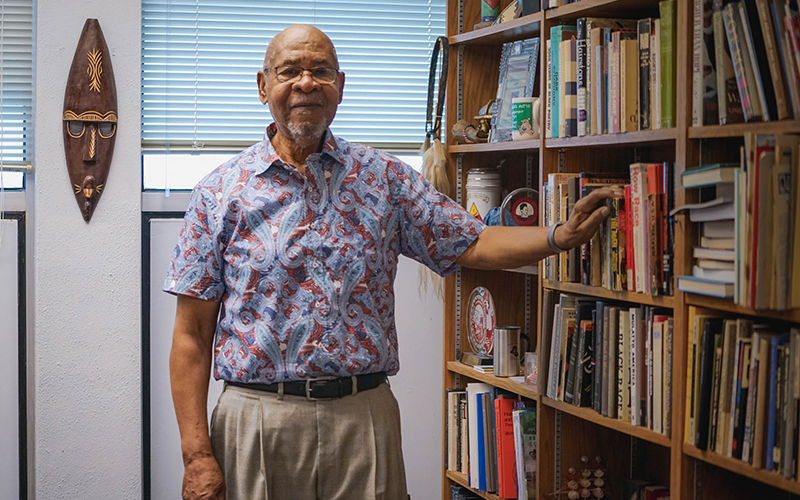

George Henderson, long-time civil rights activist and OU professor emeritus, marched arm-in-arm with students. At the time, Henderson praised Boren for his “swift justice.”

Looking back, Henderson feels conflicted.

“All the members of that fraternity were declared guilty without an opportunity to speak otherwise,” he said. “We can’t undo what happened on that darn bus. But we could have done a lot more with how we would go forward on this.”

Henderson led a mandatory social-justice workshop for the remaining members of SAE.

“We put the scarlet ‘R’ of racist on them (SAE members) and … we didn’t give them an opportunity to tell us who they are and what they were thinking,” he said. “Even more important than that, to show us how they can change their house and change their behavior.”

George Henderson is a long-time civil-rights activist and Oklahoma University professor. “We can’t undo what happened on that darn bus,” he said. “We can’t, but we could have done a lot more with how we would go forward on this.” (Photo by Abby Bitterman/News 21)

After the incident, OU opened a new diversity and inclusion office and mandated diversity training for all freshmen and transfer students.

Brown said the new policies, including a 24/7 bias-reporting hotline, did not fix the culture at OU, but it helps students to air their grievances.

“People don’t always listen,” he said. “They will turn a blind eye or never follow through on their promises. So I think the bias-reporting system is perfect for that because there’s documentation you can use to hold somebody accountable.”

First Amendment activists have deemed the expulsion of the two SAE members unconstitutional. Geoffrey Stone, chairman of the Committee on Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago, said Pettit and Rice have grounds to sue the public university, especially because the targets of the speech were not present on the bus.

“Even if their speech was in poor taste, what they said was completely protected by the First Amendment,” Stone said.

Brown disagreed, arguing hate speech should never be tolerated.

“Not only were they saying the N-word, but they were talking about hanging N-words from a tree,” Brown said. “That is a threat and, lowkey, could be considered a promise. What was said on that bus was hate speech, and everything they got was truly deserved because it incited fear among the community here, specifically the black community.”

Some universities have been more willing to invoke the primacy of the First Amendment. In April, Pennsylvania State University student Kaitlin Listro was featured in a video repeatedly saying the N-word. Outraged students took to Twitter and called on the university for a response. Penn State tweeted:

“We condemn racist messages as they are hateful and violate our institutional values. We cannot, however, impose sanctions for constitutionally protected speech, no matter how offensive.”

In 2017 at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, the words “white pride” were written on the Rock, a campus message board. A student alerted the university on Twitter. UT Knoxville responded in a tweet:

“While we sometimes disagree with what appears on the Rock, those who paint it are protected by the First Amendment.”

UT Knoxville’s response has since been deleted from its Twitter account.

Fight or flight: When the alt-right comes to campus

Outside speakers deemed hateful also have been controversial on college campuses. Schools are caught in a double bind, either alienating minority students or putting themselves at risk for potential First Amendment lawsuits.

The most notable speaker is alt-right leader Richard Spencer, a primary organizer of the Unite the Right rally.

Spencer began his contentious tour of college campuses in 2016. His first stop: Texas A&M University in College Station.

Preston Wiginton, 53, said he invited alt-right leader Richard Spencer to Texas A&M in hopes of introducing more diverse opinions on campus. “My white nationalism is not a morally driven one … the far left has declared war on whites with intent of annihilation regardless of creed or beliefs,” he said. “It is liberalism that promotes equality that tries to destroy diversity.” (Photo by Shelby Knowles/News21)

Preston Wiginton, 53, of Austin said he invited Spencer in hopes of introducing more diverse opinions on campus. He said he attended Texas A&M as an undergraduate in his 40s but left because of an “ultra-liberal” campus environment and close-minded professors.

“The fact that students are being so brainwashed,” Wiginton said. “That’s why I go to colleges and universities. Because who’s going to be the future judges, lawyers, professors, teachers? People who are in college now.”

Before Spencer’s visit, Texas A&M’s special-events division allowed non-university community members, like Wiginton, to reserve space on campus. Wiginton has brought far-right speakers to A&M for years, but student participation was low. Spencer’s appearance, however, drew about 400 people and at least 1,000 protesters.

Students organized the “BTHO Hate” protest, a reference to the chant “Beat the hell outta,” which A&M football fans aim at opposing teams.

“We wanted to beat the hell outta hate because we weren’t going to say ‘BTHO Spencer,”’ said Adam Key, one of the organizers of the protest. “We’re not encouraging violence. Hate is not a person. Hate is an ideology.”

Organizers said they wanted to emphasize that hate is not a Texas A&M value and Spencer’s rhetoric was not welcome.

“We protect Spencer’s – and anyone else’s – right to free speech,” Key said. “We respected that, but we also wanted to use our rights to free speech to say that we don’t agree with this.”

Although the university did not cancel Spencer, it hosted an alternate event the same night, Aggies United, which drew a diverse lineup of speakers and performers, including musicians, athletes and Holocaust survivor Max Glauben. Roughly 6,000 people attended.

“On its face, Aggies United was supposed to look like the university was taking an official stand,” Key said. “But, in reality, all the university was really doing was ignoring the problem. Having a rally about diversity doesn’t help when you have a Nazi on campus.”

Bobby Brooks, 2018 Texas A&M graduate and former student body president, agreed that the university didn’t successfully address Spencer’s presence on campus.

“A problem with higher education today is so many college campuses are very content with passive reactions to everything, and that creates space for hate to fester, to grow, to become more painful, to actually start creating painful consequences,” Brooks said.

Wiginton intended for Spencer to return for another address at A&M. But after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, A&M decided not to allow it, emphasizing the “public safety risk the event would pose.” Texas A&M specifically pointed to a press release distributed by Wiginton that read: “TODAY CHARLOTTESVILLE, TOMORROW TEXAS A&M.”

“It’s almost like we’ve gone full circle,” Wiginton said. “In the ’60s, there were people who wouldn’t allow gays to express themselves. They wouldn’t allow blacks to express themselves. Now traditional, white conservatives aren’t allowed to express themselves.”

A year after alt-right groups marched through the UVA Charlottesville campus with tiki torches, white polo shirts and Nazi flags, the university still is reeling from the impact, associate professor Jalane Schmidt said.

“We’ve been traumatized,” Schmidt said. “Everybody has been traumatized by this to one degree or another, and some people are still suffering.”

Jalane Schmidt is a Black Lives Matter activist and University of Virginia professor. Some of Schmidt’s students were surrounded by far-right protesters on the UVA campus the first night of the Unite the Right rally in August 2017. (Photo by Kianna Gardner/News21)

Schmidt said the university didn’t handle the matter adequately: students, faculty and staff were advised to just stay home, avoid the rally and counterprotest, or attend a diversionary activity.

“This is a civil rights issue of our time. We’re not going to sit this one out,” she said. “Nobody tells those who marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge with Martin Luther King that they did the wrong thing.”

Lecia Brooks, outreach director of Southern Poverty Law Center, an advocacy group that tracks hate and bigotry toward marginalized communities, said universities have a responsibility to take control of potentially hateful situations.

“The ‘First Amendment comes first’ approach is used entirely too often and leaves students to fend for themselves,” she said. “Universities need to start being unequivocal in their rejection of these outside groups and speakers coming to their campuses. Don’t turn a blind eye. Call them what they are, which is hateful.”

Safety, speech and students – how colleges proceed

As hate crimes rise, American universities are taking several approaches to remedy tensions.

Forty-two universities, 25 of which are public, have asserted their priorities about hate speech by adopting the Chicago Statement.

University of Chicago’s Stone co-created the document, which commits to defending freedom of expression above all else. The statement reads:

“It is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive. … Although members of the University community are free to criticize and contest the views expressed on campus, they may not obstruct or otherwise interfere with the freedom of others to express views they reject or even loathe.”

Public institutions have a greater responsibility to adhere to the First Amendment than private colleges, given their role as government entities, Stone said.

“Universities have to teach students how to respond to arguments and positions they don’t like without silencing others,” he said. “It’s an important skill to learn not just as students, but as citizens of a democracy.”

Mead, of the University of Mississippi, said schools are learning from each other on how to handle hate.

“For some universities, the adoption of these bias protocols has been reactive,” she said. “But there have also been many institutions who are being proactive and trying to clearly define responses for these incidents before they happen in order to provide more support and accountability.”

Abu-Hakmeh, who graduated in May from the University of Wisconsin, said it can be easy for administrators to forget that people are victims of hate on campus every day. In April, she used the university’s bias-reporting system to object to UW naming spaces in the Memorial Union for two alumni – both members of the Ku Klux Klan – from the early 1920s.

“I wanted them to know this makes me as a person of color, and many others like me, feel unwelcome on this campus,” she said. “So I thought, why not use their own system to try and solve this problem?”

In a report, university officials stated the two alumni were memorialized for the “accomplished lives they went on to lead.”

The KKK memorialization was uncovered by a campus study group that encouraged the university to take broader steps to address and remedy campus history before dealing with any specific named spaces. In a press release announcing the study, university officials stated the two alumni were memorialized for the “accomplished lives they went on to lead.” That complaint was shared with the Wisconsin Union, which voted in August to remove the names.

News21 reporter Kianna Gardner contributed to this article.

This report is part of the “Hate in America” project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project by top college journalism students and recent graduates from across the country and headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

Connect with us on Facebook.