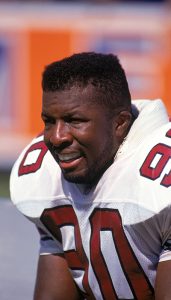

Zack Walz estimates he sustained 80 concussions during his four-year career with the Arizona Cardinals. (Photo courtesy Getty Images)

PHOENIX – Mark Maddox is left with fragments of what should be his fondest memories: He’s lost the details of a family trip to Disney World, and forgotten most of what happened in the three Super Bowls he played in. Sometimes, he watches video of his games to help jog a memory impaired by too many hits to the head.

Tyronne Stowe once anchored the Cardinals’ defense. Nowadays, he often forgets where he’s going when he’s driving on Arizona highways. He forgets that he’s babysitting his grandchild. Stowe recently covered the walls of his office with photos to remind himself of his days as a hard-hitting NFL linebacker who for years went head-to-head with opponents – literally.

Derek Kennard wears hearing aids, thanks to his history of concussions. He suffers from anxiety attacks when he’s in any crowded room and has to leave. Just two years ago, Kennard lost his last job as a guidance counselor at Grand Canyon University because he couldn’t remember his duties.

To most Americans, even to most football fans, the 2011 lawsuit against the National Football League for concussion-related injuries is all about numbers – 5,000 former players, a $1 billion initial settlement, scores of lawyers.

But for the nine former Cardinals players interviewed for this article, those numbers are irrelevant. What matters most is whether, or when, or how soon memory loss might become dementia, then a death too early for men once idolized for their physical prowess.

‘Why would you play?’

All told, there are 157 former Cardinals who played for the team since it moved to Arizona in 1988 who are among the 5,000 men who joined in the lawsuit, according to a database analysis of the lawsuit’s plaintiffs and all former Cardinals players. Those 157 represent 21 percent of everyone who’s played for the team since 1988. Another 109 players from the franchise’s days in St. Louis also joined the suit.

An estimated 15,000 other former players have more recently registered privately. Most of them are expected to file claims for benefits in the future.

“I’ve heard people say, ‘You knew it was a dangerous sport. Why would you play?’ That’s not the issue.” said Zack Walz, who estimated that he sustained 80 concussions during his four-year career with the Cardinals. “Back in the day when you would get a concussion … it was perceived as an injury that didn’t exist.”

For Stowe, too, shrugging off bell-ringing hits was his only option.

“I knew I had to play because if I missed a play or missed a game, I’d lose my position,” Stowe said. “The NFL stands for Not For Long. If you don’t do it, they’ll find someone who will. That is the pressure of everyone under that bubble.”

For the 157 ex-Cardinals, their problems go beyond health. Many of those former players have faced financial difficulties. Contrary to popular belief, most of the former Cardinals who still live in Arizona live in middle-class communities, not gated mansions.

And like many middle-class families, many live on the edge: 98 have been sued for bad debts and/or had state and federal tax agencies place liens on their property for non-payment of taxes. A third of those have filed for bankruptcy, with several former players – Stowe included – visiting bankruptcy court three or four times.

These players all knew there’d be a physical price to pay for living their dreams. But none knew what the NFL had known since 1999, when it secretly settled a case with the former Pittsburgh Steelers center, “Iron” Mike Webster, a Hall of Famer.

Physicians, both independent and league-employed, determined Webster suffered permanent neurocognitive injuries from football. The retirement board’s conclusion was tucked away for years.

The Webster case is considered the smoking gun in the case against the league. It took a decade before the NFL publicly acknowledged the link between football and brain injuries.

The 2011 lawsuit was prompted by studies conducted on the brains of deceased former football players – Webster, who died in 2002, was the first – linking the repeated blows to players’ heads to a condition known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease triggered by repetitive brain trauma.

An ongoing study at Boston University has found CTE in 110 of the 111 brains of deceased NFL players. Former players with CTE suffered from memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, aggression, depression, anxiety and progressive dementia. Some committed suicide. CTE has no treatment and can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

The lawsuit was settled in 2013, with nearly $1 billion allotted for the players. But the settlement is uncapped, meaning the cost to the league – and its owners – could balloon in the years ahead. No surprise, then, that the two sides are squabbling as the number of potential claimants expands.

For example, former players and the lawyers representing them argue that the NFL has dragged its heels on making the payments. And recently, the NFL pushed back, asserting that fraudulent claims are widespread among players seeking compensation.

Former Cardinals offensive lineman Derek Kennard (70) wears hearing aids because of concussions and suffers from anxiety attacks when he’s in crowded room. (Photo by George Rose/Getty Images)

Still waiting

So far, 1,850 players who have one of the listed disorders have filed claims for monetary compensation. Of those, just over 430 have received payments totaling $440 million – on average, a little over $1 million each.

Under the terms of the deal, players may receive up to $5 million if they have one of the neurological disorders listed as eligible for compensation in the lawsuit.

Stowe, who is among the 1,850 but has not yet received a settlement, spent his rookie year in Pittsburgh before later becoming the backbone of the Cardinals. While he was with the Steelers he banged teammates’ heads in practice, including Webster. Like many ex-NFL players, Stowe is embittered by the NFL’s years of public denial about brain injuries.

“Knowing something is wrong and not doing anything about it, that’s not being a man, that’s not being just,” Stowe said.

While the settlement has been bogged down in court, former players like Stowe sit and wait for what could be a life-changing payment.

“It would mean I don’t have to worry about tomorrow. It means I could take care of myself and my family,” Stowe, 52, said. “This settlement would equal the second-highest yearly salary I’ve ever received from the NFL.”

In his best year, Stowe said he’d earned $1 million.

Kennard, an offensive lineman who played for the Cardinals from 1986-90, said he took a blow to the head on almost every play of his career. Now his anxiety is so bad that he can’t be in a crowded room without having an aggressive panic attack.

“The room could be 30 degrees and I would break out into a cold sweat because I’m in a big room with a large group of people,” Kennard said. “These anxiety attacks usually lead to a flight response. I get shortness of breath and sweat, and I have to leave.”

Walz said from time to time he struggles to spell and define words. It can be difficult for him to remember a seven-digit number.

“Those are areas where I’m 42 and I don’t think they should be degraded as of yet to that point,” Walz said.

Maddox, who is 50, finished his 10-year playing career with three seasons in Arizona, where he still lives. Now, he’s just trying to put the pieces back together.

“When I was married we went to Disney World and I can’t tell you anything about that trip with my kids – and that’s the sad part.” Maddox said. “I’m losing those memories and those are the only things I have to hold on to.”

Now that he is divorced, Maddox said, “you lose that connection and my memories are the only thing I have, and I’m losing those.”

Stowe has spinal stenosis and nerve damage in his right arm, but he can handle the pain. It’s what has happened to his mind that overwhelms him.

“I can deal with the back pain, but the brain – the confusion, the insomnia – is different,” said Stowe, a middle linebacker who led the Cardinals in tackles in 1993. “Some nights I can’t sleep because I’m up all night thinking. I know I’m not right.”

Keilen Dykes, a 34-year-old former defensive lineman, has to go straight to bed when the migraine headaches hit. When the sun sets, Dykes feels the pain coming and will try to quell it with coffee, but soon all the lights in the house are out and he’s in bed.

Dykes, who has a job at a local trucking company, is grateful for all football has done for him and his family, even though it came at the cost of his sense of smell. Dykes’ wife, Jocelyn, forced him to see a neurologist who suggested the repeated blows to the head Dykes took as a player resulted in the severing of nerve endings in his nose.

Former Cardinals defensive end Tyronne Stowe says he has suffered significant memory problems since playing in the NFL. (Photo by George Rose/Getty Images)

Since the NFL’s public admission, the league has taken steps to further promote player safety and awareness and has put in place rules that require independent medical personnel to evaluate players for possible concussions. Some have questioned whether those steps are sufficient. But former players envy the changes.

Their playing days were filled with brutal, full-contact, two-a-day practices. That’s where they say most the damage was done.

Maddox says he suffered over 100 concussions throughout his career. Kennard believes he suffered at least one concussion every practice. To be sure, the teams employed doctors who, the players believe, were conflicted.

“Doctors were definitely more concerned with getting us back on the field,” Kennard said “Not our best interests, it was in the best interest on the owner of the team. We were medicated with pain pills, excessively.”

Players could’ve pulled themselves out of games and practices if they felt like something was wrong with their bodies. But in a sport without guaranteed contracts and 53-man rosters full of hungry young players looking to cement themselves a place in the league, most don’t have that luxury.

“Head hurts or not – you go in, unless you can’t walk,” Maddox said. “I think that comes from the mentality of the guys, too, in that you want to be out there, you have that adrenaline, you want to compete and nothing’s going to stop you from competing.”

For players struggling for a roster spot, concussions couldn’t be a concern. Walz, a sixth-round draft pick out of Dartmouth, had no room to miss time.

“If you were to pull yourself out of a game because of an injury that nobody else could see that you knew was there,” Walz said, “you immediately faced the reality that you can’t make the club in the tub.”

Dave Duerson, who finished his career with the Cardinals, was a Pro Bowl safety who won a Super Bowl with the vaunted 1985 Chicago Bears defense.

In 2011, Duerson pressed the barrel of a .38-caliber revolver to his chest and pulled the trigger. In a note to his family, he requested that his brain be donated for testing.

“CTE is truly a reversal of fortune, Duerson’s son, Tregg, said in an interview. “Around the time that my father started having symptoms our family business went bankrupt, our family home was foreclosed on. He and my mother were having marital issues. They separated and eventually divorced. When it came to the end of his life my father was frustrated, depressed.”

The Duerson family joined the class action lawsuit against the NFL in 2012 and have succeeded in securing compensation. Yet they commiserate with Duerson’s NFL comrades who have had a harder time navigating the “nitty gritty, technical process.”

Hanging on

After a devastating arm injury cut Stowe’s career short, he started two business ventures, an auto repair shop and a Farmers Insurance office. Both failed. But in 2002, he answered a lifelong calling and founded a church in Chandler. It’s helped him find peace. But not without notes: Because of his memory problems, Pastor Stowe said, he cannot conduct a service without prepared notes.

Through it all, Stowe and the other former players interviewed are mostly appreciative of their football lives, but they will always stew over how the league treats its former players.

Dykes credits football with allowing his family to live the prosperous life they enjoy. But he also blames the NFL for not educating players well enough about the long-term damage they were sustaining throughout their careers.

Kennard spends most of his time in his low-lit home in South Phoenix. He moves slowly, speaks slower.

“It was a slap in the face,” Kennard said. “They knew all along we were working with faulty equipment. (The NFL) knew about the concussions too.”

“(The NFL) has more money than anybody,” Stowe said. “They’ve got billions. Those teams are run by families. How much money could one family need?”

While confusion and depression haunts those still living, they look back on their football careers with few regrets.

“It was a great time. Would I do it again? The foolish answer is yes,” Stowe said. “It’s a one-percent chance of making it in the NFL, and I’m one of those people. I’m a part of a really elite group.”

This article was prepared for an Investigative Reporting course at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. Contributing to this report were Kiran Somvanshi and Daneel Knoetze. Database analysis was done by Professor Sarah Cohen, the Knight Chair in Data Journalism. The work was overseen by Donald W. Reynolds Visiting Professor Walter V. Robinson, the former editor of the Boston Globe Spotlight Team.

Follow us on Twitter.