SCOTTSDALE – As Robert “Bob” Lane wrapped his hand, boxing trainer Marty Barrett landed a verbal jab: “Let’s go, fat boy!”

Lane, 71, looked over his shoulder to see Barrett smirking.

“I guess that’s me. I say all these nice things about you,” Lane replied, prompting laughter. Barrett, who towers over Lane’s 5-foot frame, playfully rubbed Lane’s shoulders as Lane pulled on his white-and-gray boxing gloves to start his day of training.

Lane was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2013 and has been training with Barrett at his 12th Round Fit Boxing gym since it opened in 2016.

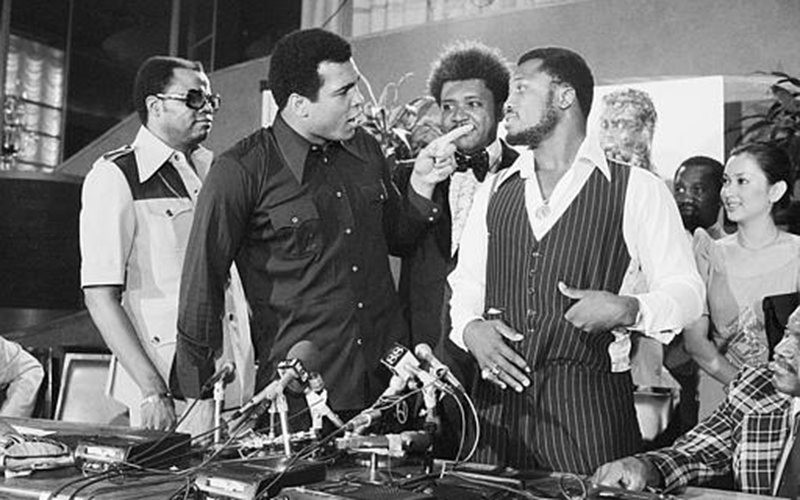

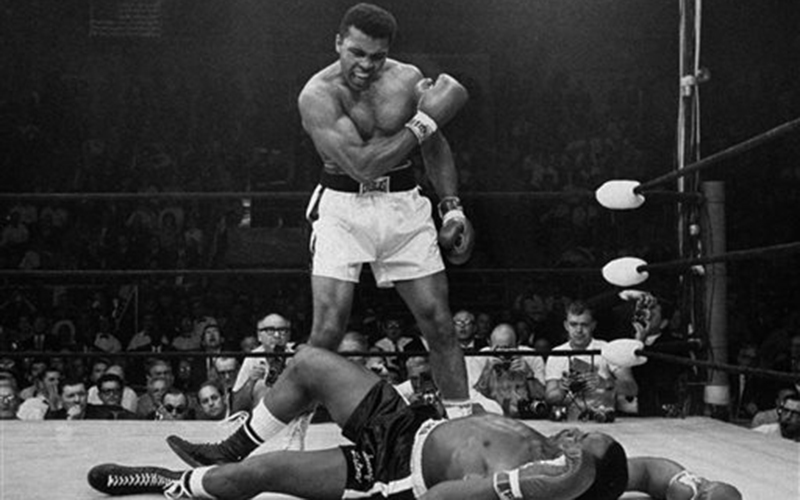

Barrett trained with such greats as Mike Tyson and Floyd Mayweather Jr. years ago. Now, two days away from the second anniversary of Muhammad Ali’s death in Scottsdale, Barrett is training people who are in the fight of their lives against an incurable disease, which the boxing legend also had.

Barrett’s gym actively trains about 60 Parkinson’s patients. Some come in to exercise once a week, others more frequently, sometimes five times a week. Blows to the head are not part of the training.

Barrett’s calling to train people with the disease — a progressive disorder of the nervous system that affects motor skills — began more than three years ago with a challenge at a different gym in Old Town Scottsdale.

“That came about because of ego on my part,” Barrett said.

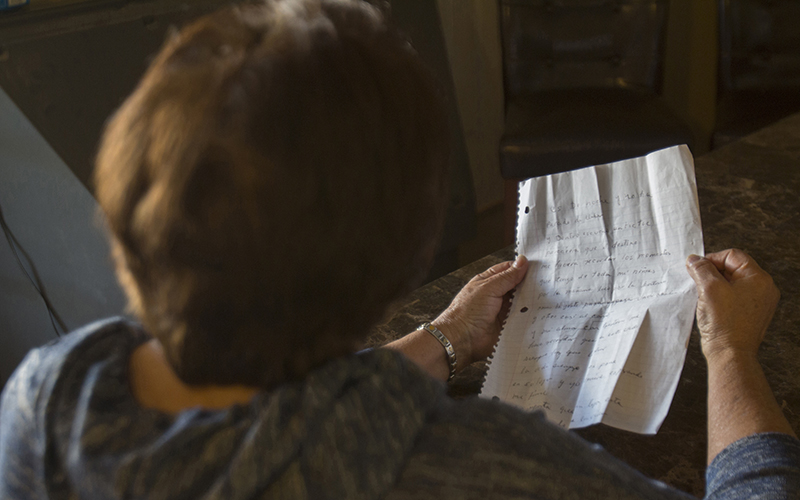

Barrett recalled a woman, probably in her mid-70s, who walked by the gym and asked whether he was a boxing trainer. Curious to see where the inquiry might go, he replied, “Yeah.”

“Can you train a Parkinson’s patient?” the woman asked.

“Yes,” Barrett said. “Is it for you?”

No, the training would be for her husband. Barrett gave her his phone number, and she said she’d bring her husband in from Chicago the next month.

Barrett acknowledged he knew very little about the disease, aside from celebrities who have it, including actor Michael J. Fox.

“I got online and looked up Parkinson’s and realized I had my work cut out for me,” he said.

The Phoenix native, who started boxing when he was just 8, said he also called neurologists he knew through acquaintances. Those doctors echoed Barrett’s thoughts that training Parkinson’s patients in the art of boxing would be a challenge.

A different pace

More than a decade after training with Tyson by running up South Mountain (Barrett said Tyson dusted everyone up the trail), Barrett made a promise to train someone whose physical abilities – due to age and a debilitating, degenerative disorder — pale in comparison to “Iron Mike.”

Barrett and his new client, Bob Wattel, began training with very basic boxing “just to see where he was at.” They focused on footwork and throwing punches with the proper form.

“Immediately, within two or three sessions, his wife was saying that she could see a difference in his walk,” Barrett recalled.

Denis Egan throws a playful punch at trainer Marty Barrett as they shadow box at 12th Round Fit Boxing gym in Scottsdale. (Photo by Ben Leibowitz/Cronkite News)

Because the gym in Old Town had stairs, which complicated things for someone with Parkinson’s, Bob’s wife, Roz Wattel, suggested training her husband in their home. This also would allow them to train more often. Barrett moved to a location that didn’t require the other clients he was training to climb stairs.

“At that point, I was already kind of connecting to the disease and connecting to the outcome that I was seeing him have,” Barrett said.

It may sound counterintuitive to use boxing training as a way to treat symptoms of Parkinson’s, a disease that an American Academy of Neurology study found veterans to be at increased risk of if they previously suffered mild brain trauma.

“We know that there’s an association between concussion or traumatic brain injury and increased rate of Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. David Shprecher, a neurologist at Banner Boswell Medical Center in Sun City.

“So, it may be a factor that increases the risk, but it’s unclear if this is a direct cause or not.”

Although there’s still no clear causal link between Parkinson’s and brain injuries — like those suffered from boxing — head injuries could bring added stress to cells in the brain connected to the disease, Shprecher said.

But there is evidence that boxing training — so long as no blows to the head are involved — can be helpful to those diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

“When I first saw it, I thought this was really strange,” Roz Wattel said of boxing for Parkinson’s patients, which she learned of back in Chicago.

But after Bob started training, she noticed improvements in his posture, motion and balance.

“But the biggest thing was improvement in mood because working with Marty was a real up,” Roz said with a smile. “It was the thing that he looked forward to during the week.”

According to a 2011 academic paper for the American Physical Therapy Association, patients displayed short- and long-term improvements in such factors as balance, gait and quality of life after undergoing a boxing training program, in spite of the progressive nature of Parkinson’s.

Dr. Stephanie Combs-Miller, a lead investigator of that study, initially became interested in boxing training for Parkinson’s patients from Rock Steady Boxing — a nonprofit founded in Indiana in 2006.

“We’ve done a number of studies even since that and we’ve found, consistently, improvement in function, improvement in walking ability, and balance, and strength and things like that,” said Combs-Miller, who also is an associate professor and director of research at the College of Health Sciences at the Krannert School of Physical Therapy at the University of Indianapolis. “To me, the most interesting thing that we’ve seen is that they improve their perception of their quality of life.”

Barrett said he’s immediately gratified when he sees his clients’ symptoms dissipate. When he’s training the “average Joes,” who sometimes box for vanity reasons, he doesn’t get the same satisfaction.

Despite the encouraging results with his first Parkinson’s client, Barrett said one of Bob’s doctors initially expressed concern, saying, ” ‘I don’t think you should box with him anymore. It’s probably a dangerous idea. He might fall.'”

Barrett invited the doctor to watch his training, and he promised he could get Bob to jog.

The doctor responded with a proposition: If Bob could jog, he’d buy Barrett any piece of equipment he wanted for the gym. If he didn’t jog, Barrett had to promise never to see his patient again, with the rationale that he was dying and needed peace.

When the doctor went to see his patient train, “He jogs about 15 yards, laughing and saying, ‘Look at me!’ ” Barrett recalled with a smile.

The doctor bought the apparatus (a numbered boxing dummy) as promised, and started sending more of his patients with Parkinson’s disease to train with Barrett.

Bob died in March 2018, and at the request of Roz and her family, Barrett spoke at his funeral. Roz said he moved those in attendance to tears, but also made people laugh with anecdotes of his time spent with Bob.

In his honor, Barrett named his Parkinson’s training program “Bob’s Way.”

Punching through Parkinson’s

The secret to his success, Barrett said, is treating everyone like a fighter. Nobody gets special treatment in the gym.

“The thing I find here is they push me,” Lane said. “So it’s tough, but I feel 100 percent better.”

Lane said he had previously gone to cardio-rehab training, which was more about monitoring than giving him regimented exercises.

The opposite is true in Barrett’s gym, where Lane tests his cognitive skills by punching a numbered boxing dummy in various number sequences, then puts that learning into practice by sparring in the ring.

“We’re boxing, but we’re not getting any blows,” Lane said of sparring. “We can throw a blow if we get in there.”

Lane has noticed positive results, such as reduced shaking and increased balance.

“That’s a key with Parkinson’s, and just getting old in general, is balance,” he said.

Denis Egan, who also trains at Barrett’s gym, said inactivity is the worst thing for someone with Parkinson’s.

“You’ve got to get up, be active,” Egan said. “Not watch ‘Judge Judy’ … which I do.”

Harvey Karchmer, like Lane, enjoys sparring the most.

“A round or two of sparring will take it all out of you,” he said. “I have more fun doing that than anything else.”

Karchmer, who was diagnosed with a slow-progressing form of Parkinson’s, is part of a clinical trial in San Francisco. He said his doctor there is “very, very pro-boxing.”

Despite being a sport that people may associate with causing Parkinson’s rather than helping to arrest it, as Bob Tedeschi wrote about for STAT News in 2016, many neurologists encourage their patients to participate in boxing training.

The Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center at Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix has run boxing classes for Parkinson’s patients since 2016.

Patty Hatton, a program coordinator at the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center who coordinates two boxing classes, said it’s the type of training and exercise that can be beneficial.

“It’s a great way to combine a lot of different skill building in one activity,” Hatton said. “The neurologists here really support it because it’s another tool in the toolbox. It is a great program for people to work at a high level — get their heart rate up — because research shows us that working at high intensity is what really causes brain change.”

Dr. Russell Teames, a chiropractic neurologist who has referred patients to Barrett’s gym, said that rigorous, high-intensity exercise is often the best way to combat the disease.

“In certain cases, the (patients) that seem to tolerate exercise or neuro rehab really well — and they can tolerate a lot of it — I send them over to Marty,” Teames said.

Barrett said boxing training helped improve the quality of life for many individuals who’ve trained under him. It’s even resulted in those individuals’ family members telling Barrett anecdotes about the noticeable improvements they see from their loved ones at home. And while the exercise and subsequent improvement of symptoms remains a clear positive, it seems to be the sense of community that keeps those with Parkinson’s coming back for more training.

“I think it’s crucial that we have places like this that take Parkinson’s seriously, but not treat you as if you’re totally invalid,” Lane said.

Barrett knows that making people feel at ease in his gym is a big part of his responsibility as a trainer.

“They don’t care how much I know. They want to know how much I care,” he said.

Modern science has yet to find a cure for Parkinson’s disease. Medications and exercises can help curb symptoms but helping to improve quality of life each day is what motivates Barrett.

“We don’t perform any miracles. But we can mask some of the symptoms for a while,” he said.

Wearing a gray shirt with black athletic shorts, Lane stares down the opponent he’s sparring with in the ring — a young boxer who’s approximately 50 years his junior.

Barrett barks instructions from inside the ring: “Shoot that right hand! Shoot it!”

Lane follows a left jab by firing his right fist into the upper body of his backpedaling opponent.

Barrett shouts out words of encouragement, “Good! That’s it! Just like that!”

On the far back wall of 12th Round Fit is a canvas with a picture of Ali, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1984, and one of his many quotes.

The quote says, “Don’t count the days. Make the days count.”

Connect with us on Facebook.