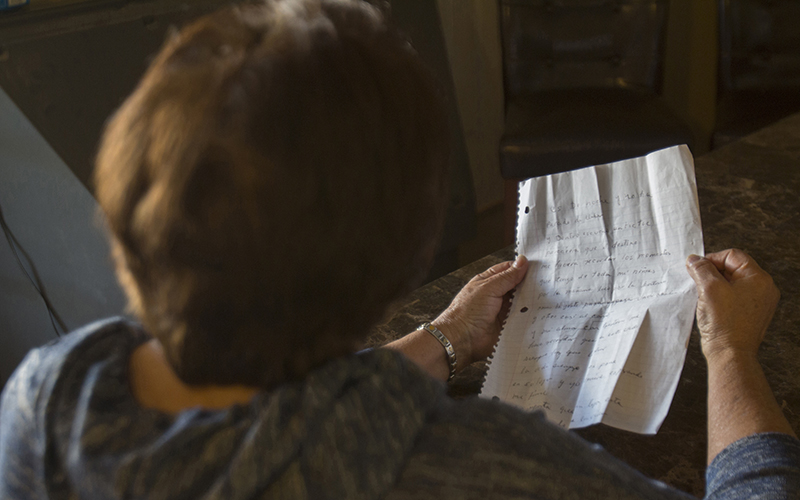

Corina Villalobos reads a poem she wrote in Spanish. Villlalobos, who has Parkinson’s disease, writes to keep her handwriting skills from deteriorating. (Photo by Blake Hemmel/Cronkite News)

Ruby Rendon (right) puts on music for her mother, Corina Villalobos, at Rendon’s Tempe home. Villalobos has been a singer since she was a little girl living in Mexico. When first diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, she wasn’t sure if she was going to be able to continue singing but still sings with her daughter. (Photo by Blake Hemmel/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Hispanics suffer from Parkinson’s disease at twice the rate of other ethnic minorities, likely due to environmental factors such as prolonged exposure to herbicides and insecticides or to metals such as copper, manganese and lead, according to a report from Washington University in St. Louis.

But many Latinos lack proper access to health care and information about the disease to begin treatment and improve living conditions, said Claudia Martinez, who coordinates Hispanic outreach programs for the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix.

“That’s why we believe that it’s very important not only to provide services for Latinos with Parkinson’s but also to educate the Hispanic community about this disease,” Martinez said. Parkinson’s disease is a chronic, neurological condition that primarily affects a patient’s movement or balance, often causing tremors.

Challenges for Latinos

Many families face a myriad challenges after a Parkinson’s diagnosis, Martinez said. About 60 percent of new patients experience depression, anxiety or apathy, according to a statement from Barrow Neurological Institute, which houses the Phoenix center.

Latinos can experience other challenges, such as a language barriers or hesitating to reach out for help.

In Arizona, 30 percent of residents identify as Hispanic or Latino, so there is a need for culturally sensitive health services for Hispanics with Parkinson’s, Sara Baird, a spokeswoman for Dignity Health, wrote in an email.

Elderly Latinos are often reluctant to be assertive with health care professionals, and many respond with silence, according to a report on Latino health care by Claudia Medina of Louisiana State University.

Language is a top barrier. The Hispanic outreach program provides services in Spanish and relies on a culturally sensitive approach, Martinez said.

‘The world came on top of me’

Ruby Rendon, a caregiver and volunteer at the Parkinson’s center, said her mother was an avid singer and dancer before she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease a decade ago.

“The world came on top of me,” Corina Villalobos, Rendon’s mother, said in Spanish. “It was something terrible.”

Rendon started looking for help for her mother.

“I did some research online because my sister told me that my mom wasn’t being the same,” Rendon said. “So I went online and looked up Parkinson’s in Spanish and I found Claudia’s phone number.”

Corina Villalobos shows a painting of women to her daughter, Ruby Rendon. Villalobos has Parkinson’s disease, and spontaneously paints whatever comes to her mind. (Photo by Blake Hemmel/Cronkite News)

Rendon said her mother looks forward to attending classes at the center, including painting, sewing, and singing in the Spanish-language choir. The center also educates families and patients about the different stages of Parkinson’s and what changes to expect.

“It’s important because you know what’s coming,” Rendon said. “You know what stage they are. And you know that if she freezes, it’s OK, because she’s going to keep moving again in a little bit.”

Villalobos, who also writes poems to keep her handwriting skills strong, said she participates in the center’s programs because of her family.

“The reason is my daughters, my family,” Villalobos said in Spanish. “They’re everything.”

Villalobos can still move and walk without help but will need assistance later, Rendon said. Then, Rendon will have handles installed in the shower and find more accessible furniture, among other things.

“I don’t try to think about it as much,” Rendon said when asked about the future. “I think we try to do it day by day, you know. This day she feels good and we can do stuff, and there’s some days when she’s probably not going to want to do anything, and it’s fine.”

Corina Villalobos wears a homemade apron at her daughter Ruby Rendon’s home. Rendon cares for her mother, who has Parkinson’s disease. Rendon picks up fabric at thrift stores for Villalobos, who keeps her hands mobile by sewing aprons at home. (Photo by Blake Hemmel/Cronkite News)

Hispanic outreach grows

The Hispanic outreach program launched ten years ago with one exercise class and a support group to improve patients’ quality of life. Since then, it has added painting workshops, caregiver training and education classes for patients and caregivers. There is also a Latino choir, Voces Unidas, or United Voices, Martinez said.

The Hispanic outreach program offers a Promotores Program that is only available in Spanish. The “first-of-its-kind” course is taught by specially-trained Hispanic volunteers who visit patients at their homes, according to Barrow’s. Promotores, which is comprised of 13 weekly visits, provides education and support.

Rendon said her volunteer work with the Parkinson’s outreach program is rewarding for patients, volunteers and families.

“You can’t do it alone,” Rendon said. “You think you can, but what I have learned is that it’s always good to ask for help if you need it.”