PHOENIX – Sister Adele O’Sullivan, a nun and doctor, once treated a homeless man who had scorched his feet walking on hot pavement.

She took care of his burns, then realized she didn’t have shoes to give him.

“We take care of whole people,” she said. “Bodies, minds, spirits. It didn’t take me long to figure out that I had to ask for help.”

She had an empty shoebox and, over the next few weeks and months, she carried it with her and filled it with cash donations. She used the money to buy clothes, prescriptions and even a cemetery plot for people who didn’t have the money to get what they needed.

That was 10 years ago. Her work now has come full circle with Circle the City, a medical facility near Third Avenue and Indian School Road that serves as many as 50 ill or dying people at a time, from a man who awoke to find himself on fire to a woman suffering from cancer. Recently, the 6-year-old facility expanded its services, opening a family health center by the Human Services Campus in central Phoenix. The 14,000-square-foot center has 10 exam rooms and 17 staff members.

Brandon Clark, chief executive, says the housing-medical clinic hybrid addresses a basic human need of people who are struggling to survive: “Where do people who have no home go to heal?”

‘Sickest of the sick’

The “sickest of the sick” are treated at the Medical Respite Center, program director Kim Despres said. It’s treatment by triage: The center gets 10 to 20 referrals a day but has to decide who gets admitted based on how dire the condition is.

Most often, admitted patients are people whose hearts are failing or whose kidney functions have slowed to a crawl. They have cancer or unmanaged diabetes. Commonly, they have injuries that people who are homeless are most susceptible to: orthopedic issues from being hit by a car and trauma from being stabbed or beaten.

People who are homeless are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior or use dirty needles when taking drugs, which can lead to sexually transmitted diseases or hepatitis C, said Ginamarie Brockdorff of the Lodestar Day Resource Center, a drop-in center that provides housing, legal and job resources to the homeless.

Brockdorff said people without shelter often are so overwhelmed trying to figure out where to sleep or how to get food that they let their health slip.

People don’t seek help until “they’ve gotten so sick that they can’t manage it anymore,” she said.

A place to heal

The respite center is a combination hospital, college dorm and military barracks, with 10 beds to a room and men and women in separate rooms. The rules – lights out at 10 p.m. on weekdays and midnight on the weekends, food allowed only in the dining rooms and no coming and going without permission – sometimes chafe patients, who spend an average of 30 days at the center.

Steve Zoraya woke up the morning of Jan. 24 to discover his leg was on fire. By the time firefighters arrived, he had extinguished the flames. He was taken to the burn unit at Maricopa Medical Center and underwent two surgeries before he was released. He stayed with his cousin for a few days, going to Parsons Health Center daily to have his bandages changed. Within a week, a doctor at Parsons called to secure him a spot at the Respite Center.

Steve Zozaya, 53, is grateful for his care at Circle the City. He stayed there two months while recovering from severe burns on his leg. (Photo by Jesse Stawnyczy/Cronkite News)

“I’ve never been to a place nicer,” he said.

Still, he’s impatient to be released. He wants to spend his days doing what he wants.

Patients report to a clinic at the center before breakfast to get their blood pressure checked, receive 24-hour nursing care and have a doctor work with them during the day. (A doctor is on call at night).

Some are eager to leave, although medical workers gently urge them to be patient enough to heal. According to Circle the City, 80 percent of patients go to transitional housing, permanent housing or in-patient rehabilitation facilities rather than return to the streets or go to a homeless shelter.

Some patients die during their stay. Pictures of deceased patients line a chapel wall at the center.

“Sister always says, the people who pass here, this is probably the only place they’ve ever been memorialized,” Despres said.

Erecting a center from a shoebox

Compassion comes naturally to Sister Adele, who belongs to the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. As a family practice physician, she focused her medical career on caring for underserved populations. While helping at Central Arizona Shelter System, she saw a gap in treatment for people without homes.

“Caring for homeless people is its own specialty,” she said.

She began carrying a shoebox with her to collect donations to fill those treatment gaps. She filled the box quickly.

“That was the love of the community in that box,” she said.

When she conceived for Circle the City, she cold-called Hospice of the Valley, asking if they knew of a building to rent. Instead, the hospice group bought the building and leased it to Circle the City for $1 a month, O’Sullivan said.

A few weeks later, construction on Circle the City began.

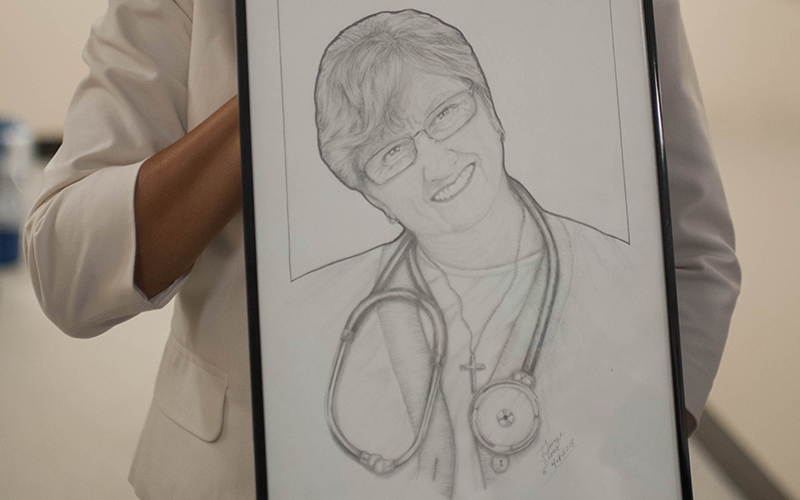

Kimberly Hall, director of development at Circle the City, shows a drawing of Sister Adele O’Sullivan done by one patient during his stay. (Photo by Jesse Stawnyczy/Cronkite News)

Follow us on Twitter.