WASHINGTON – When Maricopa County authorities got a DNA match last year from a test on a 17-year-old rape kit, they did not have to go far to find their man.

Nicholas Blackwater was serving 54 years for a series of sexual assaults between 1997 and 2001 when his name came up in the test, which connected him to a series of rapes dating back to 2000. He ended up pleading guilty to kidnapping with sexual motivation and will spend an additional four years in jail.

The rape kit that nabbed Blackwater was one of the thousands that have been tested since 2016, as the state methodically works its way through a backlog of 6,424 rape kits that had been sitting in evidence rooms for years.

By March, the state had tested 54 percent of the backlogged kits, resulting in eight hits on suspects like Blackwater. And the backlog can only get smaller: A 2017 state law requires that all new rape kits be tested within 15 days.

The tests “will bring justice to a lot of people whose cases were previously uninvestigated,” said Tasha Menaker, of the Arizona Coalition to End Sexual and Domestic Violence.

First developed in the 1970s, rape kits are a standard evidence-collection tool for law enforcement after a reported sexual assault. The kits collect, hair, fibers and other biological evidence left behind after the alleged assault, to be tested for any identifying evidence in a lab.

Prior to the 2017 law, it was up to the discretion of investigators in Arizona as to whether a rape kit should be tested. If the investigator did not believe a crime was committed or the identity of the accused was known, they often would not submit a kit for testing.

In those cases, “the question for the prosecution and for law enforcement was whether or not the conduct was consensual, so the sex assault kits wouldn’t help in that regard,” said Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery.

“Testing the kit for purposes of confirming identity is something law enforcement wouldn’t do and a prosecutor wouldn’t expect,” Montgomery said.

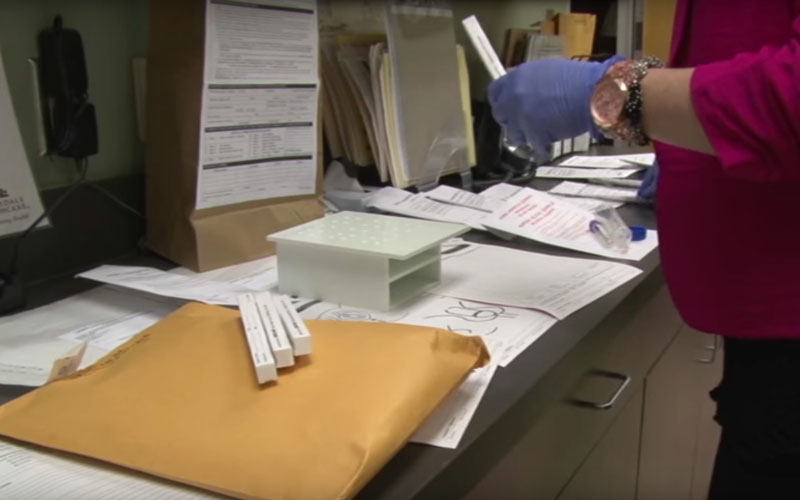

All rape kits are now tested in Arizona. Before, that decision was left to investigators, who may not have ordered a test if they already knew the accused. (Photo by Audrey Weil/Cronkite News)

But he said prosecutors have realized there was value in those untested kits as they began working through the backlog.

“You then find out that they’ve actually been involved in these he-said, she-said cases, three, four, five, six times, in which case we are actually able to build a criminal case out of repetitive conduct,” Montgomery said.

It was DNA from a rape kit collected as part of 2005 sexual assault investigation that led Maricopa County officials to Michael Paladino, who police believe was involved in a series of “he-said, she-said” cases dating back to 2003 when he was 14.

When Paladino was arrested for a traffic violation in November, authorities questioned him on the incidents. According to court documents, Paladino told officers he gets “aggressive” during sex but said the accusations were made up because “that’s what girls do.”

A grand jury indicted Paladino in December on six sexual assault charges.

Menaker, who directs sexual violence response initiatives at the coalition, said that assumptions about attackers have changed since processing these backlogged cases began.

“What we’ve learned now from testing kits that were previously sitting on shelves for several years, is that perpetrators do commit offenses against multiples of different types of people,” Menaker said. “Perpetrators will perpetrate against both strangers and acquaintances, they will perpetrate in multiple jurisdictions.”

The backlog has been whittled down with the help of $7.3 million in grants from the Justice Department and the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, as well as $500,000 the state set aside in the 2017 budget.

“We knew that we were going to need money for that backlog,” said Jessye Johnson, chief operating officer for the Arizona Coalition to End Sexual and Domestic Violence.

Advocates said the benefits of the test kits go beyond just solving more cases and putting more rapists in jail.

“An additional value of testing the kits is that it demonstrates to victims and survivors coming forward that their cases are being taken seriously,” Menaker said.

Johnson agreed that “absolutely, there’s been a lot of progress made.”

She said “more and more woman than there used to be” are coming forward after a sexual assault because they see the state is taking these cases more seriously.

There are still more kits to test and more unsolved sexual assaults but Johnson said, “progress is progress and we can’t bat our eyes at that.”

Montgomery said that even though most of the matches have come from people already in prison, that would not stop his office from seeking justice.

“We’ve gone ahead and indicted them anyways so that we can get justice for the victims,” he said.