WASHINGTON – A five-year-old law that let Native American tribes prosecute non-Natives in domestic violence cases “has fundamentally changed the landscape of tribal criminal jurisdiction in the modern era,” according to a new report.

The study released last week by the National Congress of American Indians said the 18 tribes that took part in a pilot program, including the Pascua Yaqui of Arizona. Of those tribes, 10 made a total of 143 arrests that led to 74 convictions of non-Natives who had been outside the jurisdiction of the tribal justice system before the new law.

That change was part of the 2013 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act that gave tribes a special jurisdiction to prosecute non-Natives in domestic violence cases. It provided the “special direction” from Congress which the Supreme Court said in 1978 that tribes needed to prosecute someone who was not a tribal member.

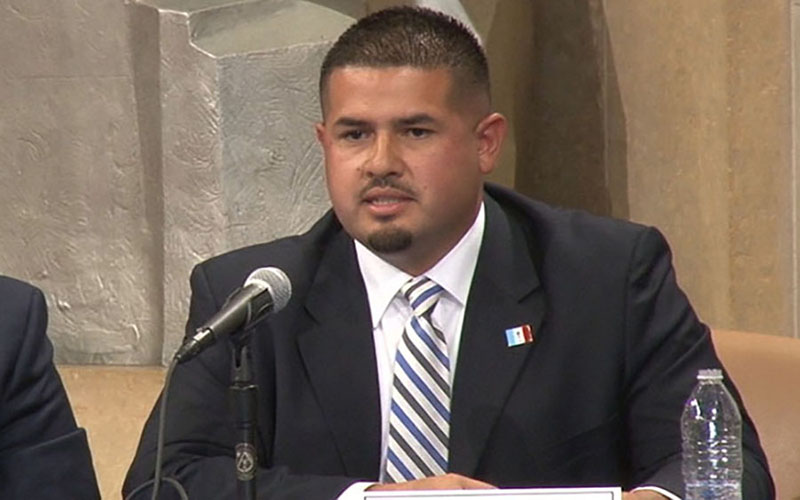

The law, which is up for reauthorization again this year, has been “a great first step” for tribal courts, said Oscar Flores, chief prosecutor for the Pascua Yaqui.

“We’ve begun the process of reviving trust in our community because we can do something” to help the victims, he said.

Flores said the law caused a “ripple effect,” preventing crimes by non-Natives who now know that they can and will be prosecuted for crimes that were once outside the reach of tribal courts.

The NCAI study said the Pascua Yaqui, one of the first three tribes to join the program and the first to prosecute anyone under it, have been one of the more active tribes. Pascua Yaqui police have arrested 40 non-Native suspects, 18 of whom have since been convicted for domestic violence.

The Pascua Yaqui arrests account for almost 28 percent of the total, even though the tribe makes up less than 4 percent of population of the 10 tribes that have actually logged arrests under the law.

Despite the advantages of the law, Flores said the limited jurisdiction prevents them from prosecuting those who commit crimes against children, the extended family or acts of sexual violence.

“Just on its face VAWA itself doesn’t account for stranger rape,” said Flores, who hopes the pending reauthorization will expand the law to give tribes greater jurisdiction.

In a written statement Rep. Raul Gijalva, D-Tucson, said the 2013 reauthorization was, “one of the most significant pieces of federal legislation in recent memory to impact the health and well-being of the women of Indian Country.”

Lawmakers said last week that they are hopeful a bipartisan VAWA reauthorization will pass this year.

“I am heartened by the fact that we have bipartisan support on this and we will keep it going,” said Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vermont, in a hearing on the act last week.

Leahy was joined by Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who said “renewing and extending the Violence Against Women Act is our next priority.” Grassley said the committee is currently working on the language of a “bipartisan” reauthorization bill.

Grijalva said he wants to see any upcoming reauthorization further expand tribal jurisdiction.

“While the 2013 reauthorization was a positive step forward, more must be done to extend greater protections to Native women and crimes committed by unfamiliar persons,” Grijalva said.

Flores agrees and hopes that successful enactment of the law will eventually allow Native American law enforcement to pursue non-Natives for any crime committed on tribal land.

“Tribes do have the capacity, it’s certainly something that’s viable,” Flores said. “We’re really excited to keep moving forward and one day have complete criminal jurisdiction.”