Arizona’s Good Samaritan law, which takes effect in April, is meant to protect those who report opioid overdoses from being arrested on a drug-related offense. (Photo by Johanna Huckeba/Cronkite News)

DOLAN SPRINGS – From his days as an undercover narcotics investigator, Jay Fleming knows what it’s like to watch someone in the throes of an overdose – and watch people run away rather than call for help.

“People shouldn’t die over a bad decision,” said Fleming, who worked for the Spokane Police Department in Washington and has since retired from a law enforcement career.

Fleming applauds the passage last month of a Good Samaritan law to shield people from arrest or prosecution if they help an overdose victim.

Arizona became the 41st state in the U.S. to enact a Good Samaritan law, one measure in the Arizona Opioid Epidemic Act to combat the crisis. Once the law takes effect in April, people who offer aid will not be prosecuted for a drug crime, but they still could be arrested for other crimes.

The Legislature passed the law after an Arizona Department of Health Services survey, mostly of health care professionals, showed respondents believe enacting a Good Samaritan law allowing bystanders to call 911 was a good way to help fight the opioid battle.

Since mid-June 2017, there have been more than 5,500 suspected opioid-related deaths in Arizona. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says “115 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose.”

Fleming has witnessed firsthand the toll of the nation’s opioid epidemic.

“When I worked undercover, if you’re doing drugs and something goes wrong, anything, you’re not going to call police,” Fleming said. “They’re the last people you want to see, especially in an overdose, because everybody has drugs that are theirs.”

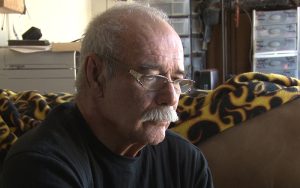

Jay Fleming, a former undercover narcotics investigator, hopes the Good Samaritan law saves lives. (Photo by Tyler Fingert/Cronkite News)

Witnesses’ fear of prison means someone in the throes of an overdose may not get the emergency help they need.

“I understand the drug war is about arrests, and the more arrests you get the more money you get from the feds, but that shouldn’t even come into play when someone is going to die,” Fleming said.

People who don’t abuse drugs still should understand the depths of addiction, he said.

“Everyone thinks if you use heroin you’re a bad person. These people get addicted and there’s not much they can do,” he said.

State Rep. Jay Lawrence, R-Scottsdale, sponsored a similar bill earlier this year, before it was included in the larger Opioid Epidemic Act passed in a special session.

“It’s important to push because I think it will save lives and it’s very good because there’s a crisis, there’s an absolute opioid crisis,” he said.

State Rep. Eddie Farnsworth, R-Gilbert, told the Associated Press before the vote on the opioid act that the Good Samaritan provision was “a get-out- of-jail free card.” But he later voted in favor of the opioid act, which Gov. Doug Ducey had worked out with legislative leadership.

Texas is one of nine states without a Good Samaritan law. In 2015, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott vetoed a bill that basically would have granted immunity to those who reported an opioid overdose, saying, “It lacks “adequate protections to prevent its misuse by habitual drug abusers and drug dealers.”

Subscribe to Cronkite News on YouTube.