TEMPE – On New Year’s Eve 20 years ago, Pat Tillman walked off a field in El Paso, Texas, representing Arizona State football for the last time.

No one knew how the next 6½ years would unfold, that he would become a symbol of perseverance, of selflessness, of bravery, and, ultimately, of sacrifice.

“I wasn’t entirely sure where he’d play in the NFL but knew he just needed an opportunity,” former ASU teammate and offensive lineman Kyle Murphy said. “Once football ended, I figured he’d go into business. Create/own his own business. Get married and have kids. Marrying Marie and having a family was so important to him.”

Tillman did play in the NFL with the Arizona Cardinals for four seasons before turning down a contract offer of $3.6 million to enlist in the Army. He did marry Marie Ugenti, his high school sweetheart, but his other dreams ended in 2004, when he died in Afghanistan serving his country, leaving many who were close to him mourning the death of a man who held so many positive qualities.

“He was in the moment and owned whatever he did,” longtime friend and former ASU and NFL quarterback Jake Plummer said. “I miss him dearly, along with these other guys. He checked on me prior to his last deployment. That’s the kind of friend he was. I should have been checking on him, but he was checking on me to see how I was doing. That says a lot about his character.”

The player

If there’s a single play that symbolizes Tillman’s career in Tempe, it’s this one:

Arizona State needed a three-and-out. It was a 1995 road game against 10th-ranked Oregon at Autzen Stadium, one of the toughest places to play in the then-Pac-10 Conference. ASU’s defensive coordinator called for linebacker Tillman to tackle the quarterback on third down. Instead, Tillman told a teammate to make the play. ASU got the stop and eventually went on to win 35-24.

“We needed this stop, we needed this down,” said Perry Edinger, a former athletic trainer at ASU. “The team goes out, and Paul Reynolds gets the sack. I was standing next to the defensive coordinator at the time, and he said, ‘Paul, that was great, but that wasn’t what you were supposed to do. Why did you do that?’ ”

According to Edinger, linebacker Reynolds looked at defensive coordinator Phil Snow and said, “Once you called the play, I just did what Pat told me to do.”

That was typical Tillman, wanting his teammate, who didn’t play at the same caliber, to have the glory. That’s typical of the favorite memories of those close to the player, who will be remembered for his military service, as well as the man he was on and off the field. For his efforts his senior season, he was named the Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Year.

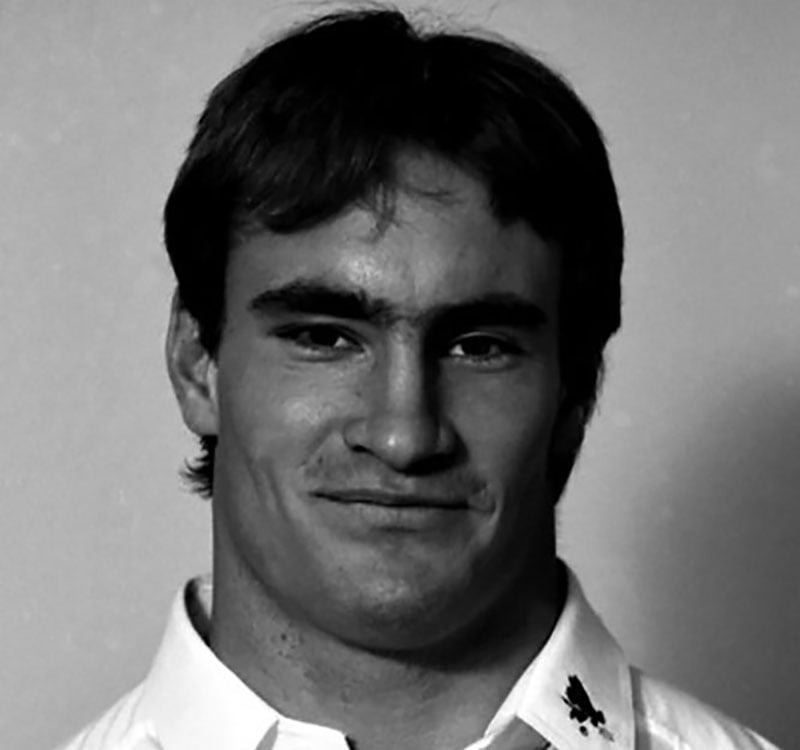

Pat Tillman in his playing days at Arizona State University. (Photo courtesy Sun Devil Athletics)

“Pat didn’t need the glory,” Edinger said. “I remember Pat saying, ‘Coach, I knew what they were going to do, I just told Paul what to do,’ so in a situation where we needed a stop, he turned it over to somebody else. That was who he was.”

That Saturday afternoon in Eugene was one example of many that described the character of Tillman, teammates said. According to Plummer, Tillman was a friendly man who was dedicated to success. He wanted to bring the best out in everybody, including teammates, coaches and trainers.

“Once you became a friend of his, you realize how much of a good friend he was,” Plummer said. “He was always there for you. He was always challenging to be a better human and a better man.”

In his time at ASU, Tillman earned top recognition from both the school and the conference. In 1996, Arizona State went undefeated in the regular season and made it to the Rose Bowl. A year later, Tillman was named the conference’s top defensive player and ASU’s most valuable player.

Not surprisingly, in his last game — a 17-7 victory over Iowa in the Sun Bowl on Dec. 31, 1997 — he finished his career strong, with eight tackles (four solos), a pass breakup and three quarterback hurries.

Tillman’s selflessness shined between the buttes of Sun Devil Stadium. He not only wanted to succeed, but he also wanted everyone around him to as well.

“It wasn’t about him,” Edinger said. “It was always about everyone else. He wanted to be very good, so you just kind of felt he would be.”

Serving in the Military

Tillman’s dedication to others extended beyond the football field. When the attacks occurred on 9/11, Tillman, who was with the Cardinals at the time, ended his playing career and joined the military.

“It was to be a part of something bigger than yourself,” said Jeremy Staat, a former ASU teammate of Tillman’s who served in the Marine Corps. “I was sitting in my house in Arizona watching the second plane hit the tower. I was like, ‘What the hell is happening? Are we under attack?’ it was in that moment I realized football is just a dumb game. This is real life.”

Tillman had a $3.5 million contract awaiting his signature. Staat also played in the NFL, so he know some of the struggles Tillman was going through at the time. At Tillman’s wedding, Staat tried to convince him to take the money, but after a long conversation between the two, Tillman was still not convinced.

“I said to him, ‘Hey what is going on with the contract,’ ” Staat said. “He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. I have some other things lined up.’ I said, ‘All right.’ ”

A week after his honeymoon, Tillman turned down the contract and signed up for bootcamp.

For years, Tillman suited up in pads and a helmet to play a game with his teammates. Football taught them the meaning of brotherhood, Staat said, but it couldn’t compare to the level of serving in the armed forces. Tillman put the football helmet down and picked up an army helmet to be a part of something bigger than football. The concept of playing on a team became more important when it was less about a game, and more about a potential fatal scenario.

“It’s different when you are in service. This is for life and death,” Staat said. “There is a different type of dynamic. In football, you train as a team, you win as a team and you lose as a team. But in the military, you might have to save somebody else’s life. There is a different kind of bond.”

Remembering Tillman

Following his death, Tillman was honored by many, including ASU, for his traits beyond athletics.

Before the ASU football team takes the field on game day, players walk down the tunnel in the north end zone and place their hands on a statue of Tillman that was unveiled before the season. During the ceremony, where the school unveiled the statue, then-ASU football coach Todd Graham said that players touching the statue is a way for the team to feel the presence of Tillman while representing ASU on game day.

“He embodied what we are about,” Graham said. “We’re trying to teach guys to win and be a champion in life, and that’s what we’re here to celebrate. That’s what Pat’s life was all about.”

-Cronkite News video by Ryan Curry

At the ceremony, friends and family of Tillman spoke on his behalf. His college roommate, B.J. Alford, said Tillman had outstanding qualities that no one could match.

“Now in my 40s, it’s fun to look back and reflect,” Alford said. “I was in the presence of somebody who had qualities of greatness inside of him, and I got to watch those qualities unfold right in front of my eyes.”

However, Tillman may not have liked a statue being built in his honor. Tillman was a selfless man, his friends say, who put others before himself. Plummer said Tillman loved to hear the cheers on game day, but probably would not have liked all the attention he received.

“Knowing him, he probably would be a little upset that there is a statue of him, because he didn’t like a lot of the accolades,” Plummer said. “He loved to be cheered and encouraged and feel that energy, but hey what better person to focus on and tell your children about what he did during the time he was born and the time he left us. The guy accomplished a whole lot of stuff.”

Regardless of whether Tillman would have liked the accolades, ASU still chooses to honor him because of the impact he made on the university and the Valley.

“Who would like a statue of them? Not too many,” said Doug Tammaro, ASU’s assistant director of media relations. “Pat, I know, would understand and appreciate all the good that has come out of this 14 years later.”

Tillman was a man who was with and for others. The impact he made when he was alive inspired people to celebrate his legacy many years after his death.

“You don’t think of Arizona State without thinking of Pat Tillman,” Tammaro said. “You don’t think of 42 and not think of Pat Tillman. That was our goal. We just didn’t want people to forget how much Pat meant to us, because before he was USA, he was ASU.”