Hispanics were heavily represented in construction and agriculture jobs, which were particularly hard hit during the recession, but many apparently dealt with the dislocation by starting their own businesses. (Photo by Lorenia/Creative Commons)

Lorenzo Santillan worked in restaurants during the recession but was unhappy with the jobs, so he started his own food truck business. The number of Hispanic-owned businesses more than doubled over the last 10 years. (Photo courtesy Lorenzo Santillan)

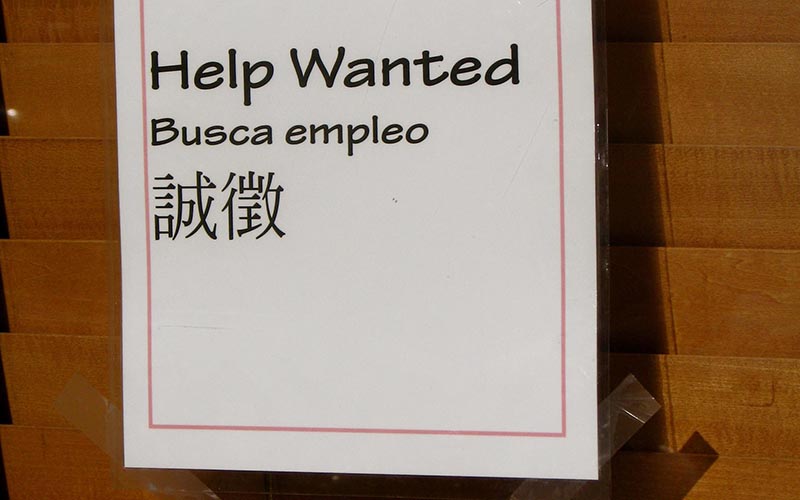

Arizona’s construction industry shed about 100,000 jobs in the recession, and that hit Hispanic workers hard. Those jobs have started to come back, but many Latinos have since gone into business for themselves. (Photo by Jeffrey Beall/Creative Commons)

WASHINGTON – When the Great Recession began 10 years ago this month, experts say Latino workers in Arizona were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Heavily represented in construction and agriculture, two industries that were particularly hard hit, and generally younger than the overall state population, unemployment among Hispanics in Arizona soared from 4.8 percent in 2007 to 13.8 percent in 2012, when it topped out. It had fallen back to 5.8 percent as of 2016.

Part of that recovery, analysts say, was the result of the situation that caused the jobless rate to soar in the first place: Locked out of jobs they were used to, an increasing number of Latinos decided to start their own businesses.

Recession reflections:

See related stories looking back at Arizona 10 years after the start of the Great Recession:

“Between 2007 and 2015, the number of Hispanic-owned businesses in the state doubled and the number of … businesses owned by Hispanic women tripled,” said James Garcia, director of public policy for the Arizona Hispanic Chamber of Commerce.

He said the 52,000 Hispanic-owned businesses in the state in 2007 had grown to 123,000 by 2015.

Latino unemployment in 2016 was still higher than the state average of 4.9 percent. But Garcia said this small-business boom, combined with a slow return of construction jobs and more young Hispanics getting college degrees has helped close that employment gap.

One of those new entrepreneurs is Lorenzo Santillan, 30, a DACA recipient who put himself through culinary school during the recession to fulfill his passion to become a chef.

Santillan said his father lost his construction job during the recession and was unemployed for two years, compelling his mother and his siblings to find any work they could to make ends meet.

After bouncing around a couple different kitchens that he did not like, Santillan decided to start his own business, a food truck called, “Ni De Aqui, Ni De Alla,” Spanish for neither here nor there.

“The reason I decided to come up with a company and become self-employed was the fact that I don’t have to wait for anybody to give me a job,” Santillan said in a telephone interview. “I can hustle and work hard and find my own gigs without waiting for anybody to employ me.”

Garcia said that type of entrepreneurship was partly by necessity, with the construction, leisure and hospitality industries in Arizona slow to recover since the recession. Chamber data show that Hispanics held about 35 percent of construction jobs and 47 percent of agricultural jobs. When those jobs, mostly held by men, were lost, Garcia said that had a “very direct impact” on families.

Eileen Diaz-McConnell, professor at Arizona State University’s School of Transborder Studies, said Latinos were hit hard because of the jobs they tended to work, their citizenship status and the fact that they are younger on average, and younger people tend to have a higher jobless rate regardless of race.

“Latinos in Arizona are young and that’s especially true of U.S.-born Latinos in Arizona,” Diaz-McConnell said. “The median age in 2014 was 20, and 16- to 19-year-olds have really high unemployment rates compared to those 20 or over.”

Another characteristic is nativity and the types of jobs U.S.-born and foreign-born workers tend to end up in, Diaz-McConnell said.

“Nationally, Mexicans are 65 to 70 percent of the population and in Arizona 90 percent of Latinos are Mexican,” Diaz-McConnell said. “So, unemployment may be related to the kinds of jobs people are in, what kinds of jobs natives and immigrants choose to work and how high of an education they obtain.”

One important thing to remember when looking at unemployment, she said, it that it’s “not just whether people have a job, but whether they’re good jobs.”

Because some can’t obtain those good jobs, Diaz-McConnell said, they may choose to start their own businesses and become entrepreneurs.

Garcia said the increase in entrepreneurs has been accompanied by an increase in the number of Hispanics in the state who are staying in school and going on to pursue a college degree.

“We’ve seen more Latinos personally going to college, more are finishing college,” Garcia said. “Not necessarily four-year degrees, but more are going to higher education.

“And all of those things are starting to have a spinoff effect in terms of the kinds of jobs that they can take and whether or not they become entrepreneurs,” he said.

Santillan said he’s seen “a lot” of undocumented youth becoming entrepreneurs and opening up their own businesses, including his own brother who is starting his own landscaping company.

“When it comes down to it, if we’re not contributing to society – I think this is the best way to prove any government wrong, that we’re here to work and better the country, not becoming rapists and drug lords,” Santillan said with a laugh.