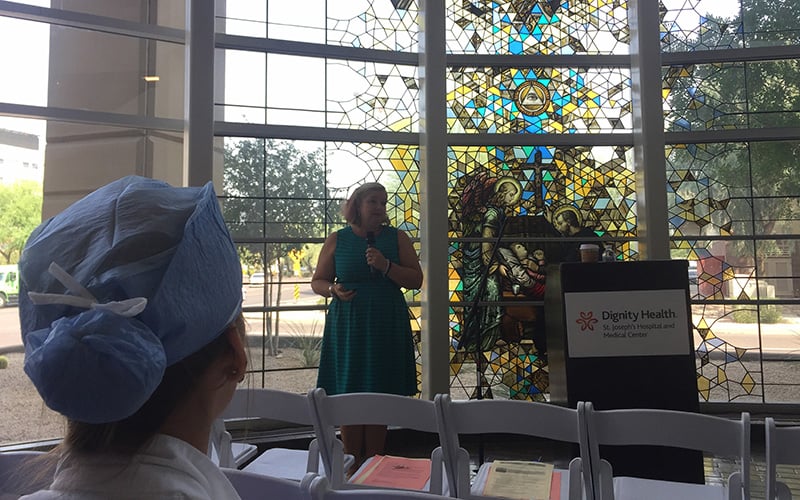

A medical worker listens as Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, who oversees a sex-trafficking intervention and research program at Arizona State University, discusses warning signs so health care workers can help victims. (Photo by Tanner Stechnij/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX – Phoenix has been identified by the Department of Justice as a major human trafficking destination but a local hospital is training health care workers to spot and help the men and women who have fallen victim to prostitution.

Personal accounts, prevention measure and treatment methods were part of a September training at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center.

Holly Gibbs survived sex trafficking as a teenager.

“At the age of 14, a man in a shopping mall convinced me to run away from home to become a model or musician. In reality, what he did was he forced me into prostitution in Atlantic City, New Jersey,” said Gibbs, Dignity Health’s Human Trafficking Response program director. “I was trafficked for two nights before I was recovered by law enforcement.”

Watching for victims of fear, violence

Gibbs and other seminar speakers told health care workers to watch for physical and psychological signs of human trafficking.

“There are so many red flags that can indicate sex or labor trafficking,” Gibbs said. “Anything from physical assault, sexual assault to signs of bruising in various stages of healing.”

Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, who researches sex trafficking at Arizona State University, discussed findings from Las Vegas case studies revealing the scope of the problem throughout the U.S.

Las Vegas research indicates three categories of violence for health care workers to learn: the visible, the less visible and the invisible.

The visible evidence is the most common and includes bruising, swelling, broken bones and other instances that point to a trafficker’s punishment.

Traffickers also discipline with sexual violence – the less visible. The most important and difficult violence to identify is the invisible psychological violence shown in submissive behavior and fear.

Combating human trafficking

A state report said Arizona is a hub for human trafficking – exploiting victims in the sex trade or through slave labor.

In Phoenix, the ASU sex trafficking research office works with victims in a more hands-on effort by setting them up with resources during “drop-in” events.

“We opened up a senior center for a whole day and people could come in only if they’ve ever been trafficked or prostituted,” Roe-Sepowitz said. “They got services, they got mental health, medical services, clothing and showers. The last time we had 58 people walk in the door. Fifteen of them were men.”

Claire Merkel, of ASU’s McCain Institute for International Leadership, told health care workers education is one of the best ways to help victims of “modern slavery.”

“The kids and even adults that you see in this situation don’t always understand that they’re being trafficked and they aren’t always the easiest people to communicate with,” Merkel said.

The public needs to help, too

Gibbs said people need to understand how abusers can lure young people and need to intervene.

“Anyone who reaches out to a younger person and offers a better life or offers a kid a chance to run away from home to become an MTV model or a video star or musician, consider what they were up to,” Gibbs said.

Lea Benson, president and chief executive of Streetlight USA, told Cronkite News “society needs to work as a team.”

“This is not an effort that one organization can handle,” said Benson, whose nonprofit provides residential services for girls ages 11-17 who are recovering from sex trafficking. “These children come from all walks of life. We specialize in those who have medical and mental issues, but the rest are no different.”