PHOENIX – Tall corporate buildings, brand new modern apartment complexes and fancy restaurants compose most of Central Avenue in downtown Phoenix. However, just a few miles down, south of Salt River, it’s a different story. Small, family-owned businesses, abandoned buildings and empty lots become the scenery.

The “south side,” as it’s commonly known, is home to predominantly low-income Latino and African-American families whose history is filled with memories of displacement and isolation.

From the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport expansion in the late 1970s – which displaced hundreds of families from the area – to the environmental impacts left by the construction of Interstates 17 and 10 across these neighborhoods, the impact is still being felt.

South Phoenix residents say they have learned that when it comes to big city projects, they need to stay one step ahead to protect their communities.

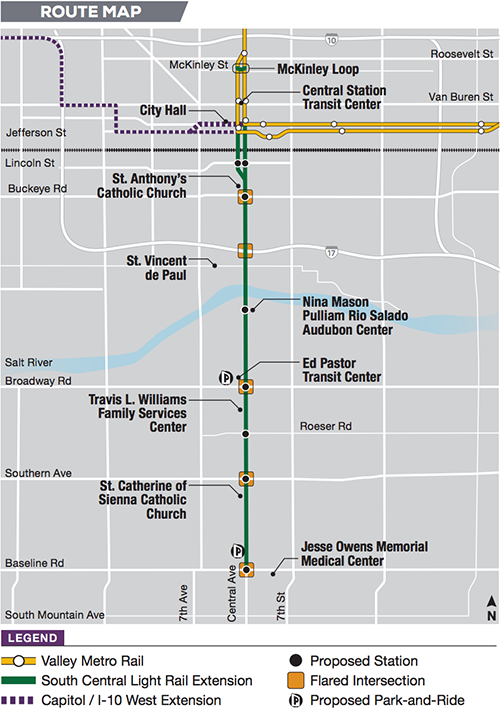

A recent example of this has been the South Central light rail extension project, which is scheduled to open in 2023, with its design phase already begun.

The project is the result of Phoenix residents voting in favor of Proposition 104 in 2015, which enabled the city to raise sales taxes and speed up the construction process, while pulling in funding for it among other economic resources.

“There’s a whole team of community residents that are meeting on a regular basis because we want to make sure that the families and the businesses are involved in the project,” said Petra Falcon, the executive director of the immigrant rights organization Promise Arizona and a South Phoenix resident for more than 40 years.

“The community has changed because of gentrification or because of the airport, there’s been lots of changes, and so this is the last barrio that’s still intact,” Falcon said. “We have to be vigilant about the process.”

Community members said part of that process includes making sure the community is reflected in the artwork that will be part of the extension. Valley Metro Public Art Administrator MB Finnerty said they usually call for local residents to be a part of the selection panels that choose the artists who will be commissioned to work on the project.

Falcon and other community members made sure they were part of those panels.

Of the 14 artists selected for the project, 10 are from the Phoenix metro area, Finnerty said. And some of them are South Phoenix residents themselves.

Therosia Reynolds is one of those artists. Reynolds was born and raised in South Phoenix in an African-American farmworker family. Her grandmother worked in the cotton fields of the area. Since becoming an artist, Reynolds said her proudest moment came when she told her grandmother her art was going to be displayed in the same place where she used to work as a farmworker.

For Reynolds and many others in the community, the light rail represents more than just public transportation. It is also a symbolic recognition that the south side is part of the City of Phoenix.

South Phoenix residents are concerned that the light rail will increase traffic on South Central Avenue. (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo Valencia/Cronkite News)

They say South Phoenix has been in many ways a forgotten, marginalized part of the city. In the early 1930s, communities of color were excluded from obtaining loans through the federal Home Owners Loan Corp. and couldn’t buy houses north of the city because they were considered “detrimental races and nationalities.” Such measures stagnated economic growth in these neighborhoods, which has had long-lasting effects.

To this day, the average household and per capita income in South Phoenix are nearly cut in half when compared to the rest of Maricopa County averages, according to a report conducted by the county’s public health department. Home ownership rates are also nearly half in comparison to the rates in the rest of the state and the county.

The Roosevelt Elementary School District currently has several underperforming schools, and life expectancy is significantly lower than in the rest of the city, according to the Center on Society and Health.

“Historically, South Phoenix was always the bastard child of Phoenix,” said Perry Ealim, member of Black Wall Street Arizona and a South Phoenix resident. “(It) was almost last on anything.”

Many South Phoenix residents, including younger generations, said they still share a sense of isolation when compared to the economic development happening in the rest of the Phoenix metro area.

“It’s just a neighborhood of, maybe the word is poverty. You come down here and you see the difference between South Phoenix and Scottsdale,” said Kevin Cray, a 22-year-old South Phoenix resident.

Cray does think South Phoenix, however, has improved since he was a kid and sees the light rail as an opportunity to continue expanding.

“I’m glad South Phoenix has grown, and it’s been better, obviously from here to 2022 when the light rail is done, it can only grow so much more and get even better,” he said.

For Martin Moreno, a former South Phoenix resident and one of the other artists involved in the project, the light rail might be a way to overcome that feeling of segregation.

“A lot of people still see South Phoenix like ‘the other side of the river.’ So it’s gonna be very important in terms of identity, economic development and being part of that inclusive process that’s gonna take place. We are a viable important part of the city,” Moreno said.

Residents like Falcon recognized the importance of bringing transportation alternatives to the south, where 28 percent of the population doesn’t own a car, according to the report done by the Maricopa County Department of Public Health. Falcon was one of the supporters of Proposition 104 and said she knocked on people’s doors to inform them about the initiative and why it was important.

But she knew that was just the beginning.

While embracing the idea of the new light rail, some residents said they are also worried about the negative impacts the project might bring. While increased traffic and pollution are among the main concerns, community members also fear the new infrastructure will increase rental costs. Sixty-two percent of South Phoenix residents pay a monthly rent, and they said it could attract outside speculators, making the neighborhood unaffordable for those who already live in the community.

Recently, Valley Metro and the city of Phoenix hosted two public “meet the team” events in the area so residents could look at the plans for the light rail and ask questions. Representatives for the design and the construction companies were also there to give information about the jobs that will be available during both phases of the project.

“Light rail projects attract a lot of development, this project could deliver more than 10 times the benefits of the money we put in,” Phoenix Councilwoman Kate Gallego said during last Thursday’s meeting. “We’re going to make sure that those benefits help the people who are already here in addition to the new businesses and community members who are going to be coming.”

Community leaders said they want to make sure residents will benefit from the job creation and the economic spillover that go along with the light rail extension.

One of the seven new stations will be on Broadway Road. (Photo by Andrea Jaramillo Valencia/Cronkite News)

The solution, Falcon said, is “gente-fication.” Gente means “people” in Spanish, and they use the word to suggest that the community will take an active role on the gentrification that might come.

Ealim said he wants to go even further. He thinks government officials shouldn’t offer only entry-level opportunities ‒ in construction workers or janitorial positions ‒ when they promote jobs within low-income communities. He said he wants to see decision-making positions too.

“Most of (entry-level positions) are geared toward a dead end, that you go to a certain level and then there’s not a glass ceiling, a concrete ceiling, that they can’t get through,” Ealim said. “The light rail could be so beneficial to so many people in South Phoenix, if it’s done properly.”

Reynolds thinks South Phoenix is ready for whatever challenges may come with the expansion and the changes to the community it may bring.

“We can contribute, we can be a part of what’s going on,” Reynolds said. “We are people of tenacity, we are people of struggle.”